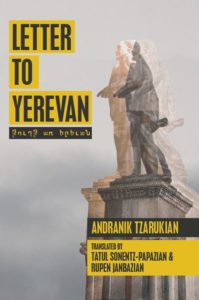

Andranik Tzarukian

Translated by Tatul Sonentz-Papazian & Rupen Janbazian

Hairenik Press, 2018

119 pp.

$14.95 paperback

A short while ago I read about Tatul Sonentz-Papazian and Rupen Janbazian’s recent translation of Թուղթ Առ Երեւան by Antranig Tzarukian. Having read a few of Tzarukian’s other works, such as Սէրը Եղեռնին Մէջ and Մանկութիւն Չունեցող Մարդիկ, I naturally felt compelled to read this landmark work. The first time I had heard about Letter to Yerevan was a few years ago when I would study Armenian with a former Saturday school teacher of mine, Mr. Antranik Tchelanguerian, during my university years. He had told me about Tzarukian’s ingenious response to Abov’s sharp-penned poem openly criticizing the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF).

Having ordered a copy of the translation upon receiving news of its publication, I was anxious to open its contents and delve into a piece of history that had seemed to fade away from our collective memory. Upon reading Abov’s poem, I could not help but feel that it was offside and exaggerated. His frequent use of the term ‘dogs’ made me question his national disposition, needless to say his character. Nevertheless, this petty attempt to degrade the party that propelled and secured the first independent Armenian Republic instigated one of the most prominent prosaic works in contemporary Armenian literature.

I read the entire work in one breath and was able to do so because of its captivating and moving form of expression. Tzarukian’s passionately penned defense, intertwined with the history of ARF figures, the element of exiled patriotism and deep-rooted yearning for national independence and freedom teleported me to an era I would have liked to witness first-hand.

I decided to read the work in Armenian, only referencing the English when the Armenian surpassed my understanding. Sonentz-Papazian and Janbazian made the insightful decision to offer both languages in the recent publication, in recognition of a new generation that has seen the unfortunate degradation of the Western Armenian tongue. But it was in my stubborn attempt to focus as much as I solely could on the Armenian text, that I really was able to grasp the depth of Tzarukian’s work.

Tzarukian’s passionately penned defense, intertwined with the history of ARF figures, the element of exiled patriotism and deep-rooted yearning for national independence and freedom teleported me to an era I would have liked to witness first-hand.

For those who are unfamiliar with Tzarukian, he is a Western Armenian writer born in Goruyn in 1913. As a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, he was orphaned in Aleppo, from where his fictionalized memoir, Մանկութիւն Չունեցող Մարtիկ took birth. Tzarukian, despite being prominently a novelist, took it upon himself to write the prose, Letter To Yerevan in Eastern Armenian, thus making it more accessible to the Soviet Armenian audience.

Tzarukian’s tone throughout the poem intends to strike camaraderie, empathy, understanding and unity through the referencing of collective Armenian historical events. Throughout the prose, Tzarukian refers to Abov as ‘distant brother’ or ‘contented comrade,’ and this in and of itself elevates Tzarukian’s character and literary appeal.

In short, this work truly was a timely translation and publication that rekindled a moment in our collective consciousness. It is also a call to action, reminding us of the importance of literary translations, the inspiration they ignite for further literary creation and cultural progression. May this stepping stone lead to a զարթօնք of Armenian literature, rekindling the voices of our prolific writers that have remained in the shadows now for far too long.

Editor’s Note: All proceeds are donated to the Hairenik Association’s newspaper digitization project.

I had heard of this poem of course, but never read it. It had generated a certain antipathy in me—for both Abov’s tirade and Tzarukian’s ‘rebuttal’. I had been variously urged to read it as a great work of ‘truth’, or else been told that it is a distillation of the awfulness of the ARF that should never have seen the light of day etc. etc.

Two years ago I was given a copy of a 1960s edition from Beirut by some very ardent acquaintances who were convinced I should read it. Again, I was put off, this time when I saw that the poems are in Eastern Armenian. So, this translation by Tatul Sonentz-Papazian and Rupen Janbazian is a boon for me—and I cannot praise it enough.

Also of great value is the ‘Eight Introductions: Variations on a Common Theme’ by Vahe Habeshian, who explains much about the Soviet-Armenian animosity for the ARF (an aversion which persists in Armenia today, I venture). Bolshevik propaganda was highly effective it seems, even leading to the fall of the first Republic of Armenia. And too often we forget—or air-brush out of the modern Armenian narrative—the persecution and imprisonment in Russia, Yerevan and Baku, of political and military figures; many heroes of independence battles, and the eventual murders of some 50 of them in Yerevan’s jails in 1921. The purges of Armenian artists and political figures—often accused of being nationalists, ARF members and sympathisers–during Stalin’s Great Terror (in Armenia starting in the mid-1930s) continued unabated, even after the disbanding of the ARF within Armenia.

Abov’s work was part of the campaign to undermine the ARF during the Soviet programme of repatriation of Armenians from the Diaspora to Soviet Armenia. Abov squarely blames the ARF for all of the ills of the nascent Soviet Armenia. It is of course, written with an eye to Stalin, and a vindication of the Soviet in the aftermath of World War Two when Stalin deployed huge numbers of Soviet citizens—not forgetting the nearly one third of the population of Soviet Armenia.

The ARF made overtures to Germany in the hope that Armenia could be freed of the Soviet yoke, should Nazi Germany be victorious. This is the great betrayal at the centre of Abov’s poem ‘We have not Forgotten’. And this is why the ARF is called ‘Dashnak dogs’ over and over again, and their ‘master’ the ‘ravenous wolf’ or ‘the bloodthirsty Black Molloch’. Ironically the latter two would have made rather good epithets for Stalin.

Abov implies that that sin of allying themselves with the Nazis, is the greatest and most unforgivable sin against the (presumably) benevolent regime of Soviet Stalin.

The ‘letter’ from Tzarukian is an often meandering and rather long rebuttal of Abov’s assertions. Tzarukian brings to life the grieving of genocide survivors (as he was):

“What does he have? No father, no shelter, no child,

Not a single sliver of land in this wide world,

Nowhere under the sun to call home:

In constant struggle to find his daily bread,

He has nothing, except sorrows…”

and he chastises Abov for discounting the pain from which the Republic was born, and the sacrifices of the fedayi. He reminds Abov of the dreadful years of the early Armenian Soviet, when militant nutcases such as Avis Nurijanyan, imposed Soviet rule on an already impoverished, starving, and uncomprehending peasantry. He rightly eulogises those who brought about the Republic against the odds

“The timid slave turned to warrior”

and describes it with wonderful imagery:

“…Seas of blood and sorrow.’

“The sky was frozen and God was absent…”

“We, travellers forgotten at the shore…”

It ends with a paean to Yerevan, and its endurance against all odds. The one sentiment which I did not understand is the one in the stanza:

“Yerevan, my only one,

Until I turn to ash and dust

I will sing of your red flag

For it guards your body from the hyena’s fangs…”

Is Tzarukian saying that the (1944) Soviet is good after all? That it is the protector of Armenia? I did not understand who the hyena is.

However, even if I still have not grasped the whole of the poem’s sentiments, it is of value and does have some elegiac passages of great beauty.

In these days when Dashnaktsoutioun has been discredited and more or less hounded out of the Republic of Armenia, it is important to have made this poem accessible to all. For it does put in perspective the importance of the Dashnaks in the history of the struggles for an independent Armenia.

Sonentz-Papazian and Janbazian have done a great job in translating this very difficult, important, and misunderstood work.