On April 25, 1915, just a day after the mass arrest of Armenian leaders in the capital of the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople, a large force of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzacs) landed on the Gallipoli peninsula as part of an allied effort to capture Constantinople. Although the campaign ended in defeat for the allies, it is regarded by most Australians today as a seminal event in the formation of their national identity. The anniversary date of the landing—April 25—has become Australia’s most significant national day with nationwide parades commemorating the sacrifice of those who have served and died in all wars.

Despite the strong coincidence in the dates and geographic setting, the Armenian Genocide has been largely excluded from official and popular accounts of Australia’s First World War experience. Why this was the case had intrigued me from a very young age.

As an avid antiquarian book collector and an independent researcher for the Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, I knew that the Australian press, along with its American and European counterparts, widely published news of the Armenian Genocide, but why had it faded from Australia’s collective memory of the war? Was there a more intimate connection between the two events that had not yet been explored? I decided to make it my mission to find out.

Beginning in the late 1990s, my research centered upon the experiences of the more than 200 Anzac prisoners captured by the Ottoman Army during the war and interned, as I surprisingly discovered, in the homes and churches the Armenians were forced to abandon. At the end of the war, the experiences of the surviving prisoners were recorded in both official repatriation reports and published memoirs. Almost without exception, the prisoners recorded encounters with Armenians, especially Armenian doctors serving in the Ottoman Army. Many of the prisoners also witnessed events surrounding the Armenian Genocide such as the deportation of women and children on the Berlin to Baghdad railway. I came to realize that there was a new body of evidence emerging that corroborated the neutral German and American eyewitness accounts of the genocide.

The next phase of my research focused on the humanitarian relief response by Australians both at home and on the battlefield. As Anzac forces were stationed in Egypt and much of their Middle East campaign was fought on the Palestine/Syrian front, it seemed highly likely that evidence would emerge on Australian encounters with Armenian Genocide survivors in the region, and indeed there was. During their advance in March 1918, Australian forces liberated thousands of Armenian genocide survivors east of the Jordan valley. A few months later, an Australian Colonel Stanley Savige, led a small elite force that defended a column of some 50,000 Armenian and Assyrian refugees fleeing the invading Ottoman Army in northern Persia. Most of the refugees survived the exodus and were settled in refugee camps in today’s Iraq thanks to the efforts of these men.

The availability of digitized newspapers by the National Library of Australia in 2008 yielded a treasure trove of articles on the subject which provided great leads for further archival research. Interestingly, I discovered that the news reports in Australia of the genocide produced outrage and a subsequent nationwide humanitarian relief effort to help aid survivors. The relief movement was closely linked to the larger British and American relief effort through organizations such as the Near East Relief (NER) organization. The Australian response culminated in the establishment of an Australian-run orphanage in Antelias, Beirut, for 1700 Armenian orphans, in 1922.

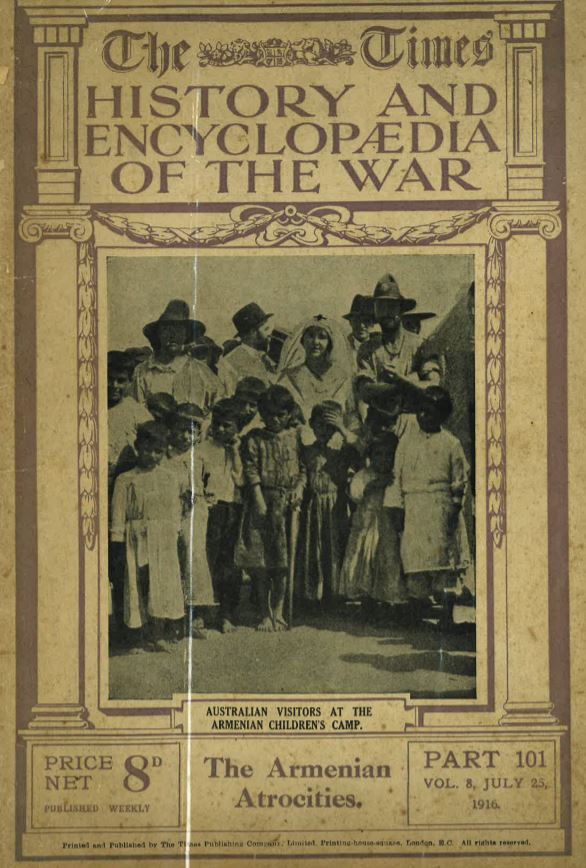

Locating documentation about Australia’s relief effort was no easy task. Having been a largely non-governmental initiative, only scant material could be found in state archives on the various Armenian relief funds in Australia. I had to think outside the box. It turned out that most of the important information was to be found in the private archives of the descendants of Australian relief workers who had worked with the Armenians. I was assisted in this endeavor largely by the services of a genealogical and heraldry society that specialized in family history research and by a NER expert, Missak Kelechian. The latter furnished me with copies of many never before seen photographs of Australians among Armenian refugees and orphans. One very powerful image would become the signature photo of Australia’s relief effort, and a major catalyst in my endeavor to search deeper into the history. It shows Australian relief workers among hundreds of Armenian orphans in front of the Antelias orphanage with the Australian flag flying proudly on it in 1923.

It was soon evident that a narrative was developing that not only shed further light on the Armenian Genocide, but provided a fresh dimension to Australia’s First World War experience – one that had either been forgotten or ignored. My next dilemma was to decide on how to get this narrative more widely known. I began to write articles that focused on the different aspects of Australia’s connection to the Armenian Genocide such as individual, state and gender perspectives for Australian peer-reviewed history journals.

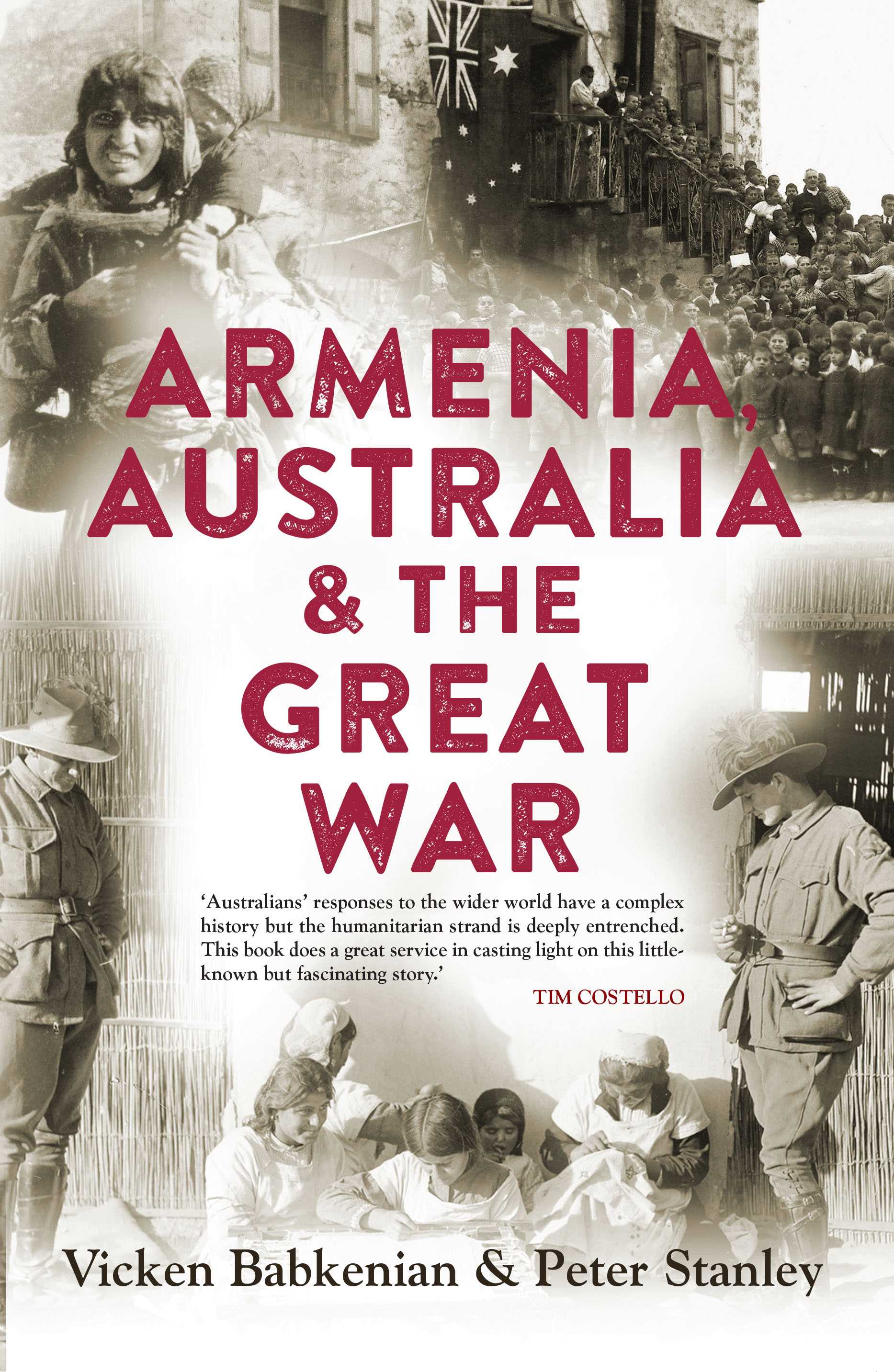

It was during this time that my work caught the attention of one of Australia’s most prolific military and social historians—Professor Peter Stanley. He had been the principal historian for the Australian War Memorial and the author of about 30 books on Australian history. Aware of the historical reality of the Armenian Genocide and the ignorance that prevailed in Australia, he believed that a more detailed and comprehensive narrative needed to be told in the form of a book. He offered to collaborate with me on such a project. With the help of a literary agent, we succeeded in finding a good publisher—NewSouth Publishing—that was very enthusiastic about the project. We began to draft the manuscript in 2013 and completed it for publication in April 2016.

The book had a major point of difference from the many other narratives on the subject. We weaved into the story many strands of Australian and Armenian history, including ancient, modern, military, social, women’s, migration, religious, humanitarian and much more. We have been greatly encouraged by the response the book has received by scholars and the wider public. One reader likened it to a traditional Armenian rug with many colorful threads and patterns running through it, which gives it a distinctive appeal. Their observation was echoed by the many positive reviews the book received in national and international newspapers, magazines and journals. Prominent journalist for the Independent Robert Fisk called it a “highly researched volume … with irrefutable proof of the Armenian genocide.” Another reviewer thought the book was “remarkable in its ability to present one of the most complex conflicts of the twentieth century with great clarity” adding that it was “informative, innovative and a pulsating read all the way through.” We were very pleased the book gained further recognition by being shortlisted for two major Australian literary awards.

However, the most gratifying part in this literary journey for me is seeing the book’s influence on the emerging academic and popular narratives on Australia’s First World War experience. The Armenian Genocide is no longer completely ignored like it once was.

I am not surprise of Australian generosity and the fight for freedom . I am very proud of Australians, also I has the privilege of living in Sydney for 36 years of my life and I enjoy every minute of it.Now far away for family reasons I STILL CALL AUSTRALIA HOME. God bless the People of Australia

I noticed a typo in my comment above. Please take the one below.

Վարձքդ կատար, Վիգէն Պապիկեան։ Ծանօթ եմ գործիդ։ Նպատակդ լաւագոյնս իրագործուած է։ Մաղթում եմ ուժ ու կորով՝ նոր յաջողութիւնների հասնելու։

Ռուբինա Փիրումեան

I am very proud of my cousin Vicken whom we met in 2005 in Sydney after lifelong search, lost relatives were found “The Bablanians” since the terrible massacres of Armenians by The Turks in 1915. Vicken’s researches and achievements adds more light on The Armenian Genocide.

The PM Churchill mentioned in his book about general Antranig’s advise, to attack from Cilicia and not from Gallipoli. Is it true?

Hi Bedros. Yes, Boghos Nubar had proposed an attack from Alexandretta in November 1914 but it was rejected by the British. They instead decided to land at Gallipoli. See article by Dr Andrekos Varnava “French and British Post War Imperial Agendas …. formation of the Legion D’orient” (2014).

A journalist from New Zealand, James Robins, is doing research on this subject too. Here’s a link to an article by him: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/23/anzacs-witnessed-the-armenian-genocide-that-shouldnt-be-forgotten-in-our-mythologising

I am working to get my novel ‘Angel of Aleppo, a Story of the Armenian Genocide’ published. I have drafted it twelve times and have had no luck as yet with a legit publisher. The narrative in the opening chapters is based loosely on the actual life experiences of my wife Lilit’s grandmother.