La Fanfare du Négus

La Fanfare du Négus

By Boris Adjemian

EHESS, 2013

350 pp.

$28.17 paperback

This book, in French, is an interesting analysis—in the field of diaspora studies—of the Armenian community of Ethiopia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Boris Adjemian explains how and why a people from Asia Minor created a new ‘homeland’ for themselves, far from their actual homeland.

The traditional perception of diasporas is that of exile; and yet Armenians felt at home in Ethiopia, so much so that they set roots, created a new homeland, and called themselves Ethio-Armenians (Yevtobahays) with pride.

Adjemian seeks to answer several questions as to how this community influenced the modernization of Ethiopia, how it became a part of Ethiopian society, and reflects on the conventional concept of diaspora. He explores the close relationship that some Armenian settlers had with the emperors. He comes to the conclusion that that relationship was what made them feel comfortable and part of the fabric of the relatively new and open society which two emperors in particular—Menelik II and Haile Selassie I—were trying to forge.

By telling the story of the Fanfare as a starting point, he is able to elaborate on the Armenians who had preceded them, and what happened to the community in later years. It is well-known that Ras Teferi, the future Haile Selassie I, during the years of his Regency, made his first trip out of Ethiopia in 1920. En route to Geneva where he addressed the League of Nations, he visited several European countries. However, his first port of call was Jerusalem—the important gesture of a devout Christian prince.

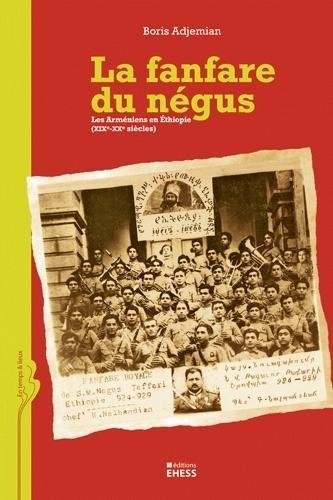

While in Jerusalem, Ras Teferi not only visited the Ethiopian monastery, but also Saint James’ Armenian Convent. In those days, the Ethiopian Monastery was in its care. There, he was entertained with music played by some orphan Armenian boys. On his return to Jerusalem on his way home, Ras Teferi offered to take some of the boys to Ethiopia, to form a marching band. Forty of them went and became known as the Arba Lijoch, which means the 40 children in Amharic.

This book raises the question of why successive Ethiopian kings and emperors were pleased to employ Armenians in close proximity to themselves on palace grounds and to do work which no Europeans were entrusted with—some in lowly positions, some in high office. Was it perhaps because Armenians did not pose any kind of threat to uncolonized Ethiopia during that era of colonialism?

Thus many Armenians were to be found in the imperial households: from cooks to chauffeurs, private secretaries, ladies in waiting to the empresses, jewelers and photographers, to a marching band whose leader, Kevork Nalbandian, composed the first National Anthem of Ethiopia, inaugurated at the coronation of Haile Selassie I in 1930, and in use until the demise of the empire in 1974.

The community was successful and close to the royal family. Many Armenian children had Ethiopian godfathers. Many Armenian men married Ethiopian women. Armenians were chosen to fill-in where Europeans wouldn’t do. They were happy with their designated function to help with the modernization of the country and be of service to the kings.

The community began to form during the nineteenth century in Harrar as Armenians arrived from the Ottoman Empire following various massacres. By 1915 they numbered about 200, including women and children. More came as a result of the Armenian Genocide, swelling the number to a maximum of no more than 1,200.

Of course, there were Armenians in Ethiopia before the nineteenth century. Most seem to have been there because of their facility with languages. There are many instances of translators who were Armenian. The Portuguese employed Armenian interpreters in the sixteenth century, as did the British who mounted a punitive expedition under Robert Napier in 1868 against Emperor Theodros.

As Adjemian admits, much of the material is from oral sources. There is not much written about the Armenians of Ethiopia, although the late Dr. Richard Pankhurst collated most of what there is. In addition they are often conflated with other foreign communities—Greek, Indian and Arab. The book mentions many colorful characters such as Sarkis Terzian—known as Telek (Great) Sarkis by Ethiopians, because of his role in procuring arms for the Battle of Adwa—and variously a rogue and charlatan to Europeans, for the same reason! Much of the book is anecdotal but nonetheless important, as it gives insight into the perception Ethio-Armenians have of themselves—as ones chosen by kings of Ethiopia to be their friends.

In addition to making many important points for diaspora studies, Adjemian has done a great service to the community (whose story has been little recorded hitherto) whose number has now dwindled to less than 80. He concentrates on the pre-Second World War years and gives an engaging account of an intrepid bunch of people.

Merci Rubina pour cette intéressante analyse.

Vous mentionnez le premier voyage d’Haile Selassie hors d’Ethiopie en 1920. Est-ce exact ?

Amicalement,

Bertrand

Thank you Mrs. Sevadjian, for reviewing this important book. As a third generation Ethiopian-Armenian, I have always wanted to read it, but haven’t been able to because it’s in French. It would be wonderful if it’s translated into English one day. Maybe the Ethio-Armenian community spread throughout the world could raise the funds to have it translated. It will help preserve our unique story for future generations.

Thank you, Rubina, for this insight. Pity the book is not in translation.