From the December 2019 Special Anniversary Magazine Dedicated to the 120th Anniversary of the Hairenik and the 85th Anniversary of the Armenian Weekly

By Tovmas Charshafjian, Hairenik’s Founding Editor (1899-1900)

Do you know how the Hairenik was born into this world? Let me recall what I can of that nativity.

Along about the 1890s, H. Eginian, the father of Armenian journalism in America, a member of the then tiny Armenian community of New York City and northern New Jersey, produced in succession his pioneering Arekag, Sourhantag and Azadoutiun newspapers. These publications lasted only for brief periods of time.

When Hagop Baronian, the immortal Armenian humorist, saw a copy of the first issue Arekag, he commented that “this sheet ought to vanish over the horizon.” It was as if Eginian heeded this sentiment. One after another, his three newspapers in fact “vanished over the horizon.”

Another early editor was a certain Arvadian. His publication was called Ararat.

Almost concurrently, Dr. Kaprielian opened publication in New York City of a colorless personal venture masted Hayk. For a time, this editor ascended public stages and “growled for Vasbourakan the Lion… Where prithee is Portukalian?” But the day after the Bank Ottoman incident, he growled “long live the bomb.” So the press run of his paper achieved the lofty figure of 300. But soon, it had no more than 75 to 80 subscribers—and it succumbed.

Meanwhile, in Worcester, the Capital City of Armenian America, two friends, (S.) Shagholian and Boyaiian, as if it were their principal objective to insult the immortal Mesrop Mashtots, tried without any success whatsoever to publish an Armenian newspaper.

These failures did not change the situation in America one iota. The existence of a vigorous press is important both to a small community of people and to political parties. The lack of a press presence was sorely felt, but it was also felt that it would take an impossible miracle to establish a responsible, scientific and literary newspaper for Armenians in this country. For, as it was widely accepted, the first prerequisite towards the establishment of a paper is to find an editor.

In those days, about 30,000 Armenians were scattered over the broad face of America.

These people were usually out of contact with one another and totally out of reach of the Motherland. There were on the scene only two organs issued by political parties abroad which, now and then, printed somber news of events abroad…meant for members of those parties.

One night, during a severe New York rainstorm, I bumped into Eginian while walking up 3rd Avenue. Seeking shelter, we ran to Ghoomrigian’s tailor shop on 41st Street.

An Armenian tailor shop could always be found in those days in any large community of Armenians in the United States—also an Armenian barber, a grocer and a baker. These stores served as forums of the Armenian community, for “hot-stove” discussions on the community’s affairs, on matters relating to Armenian political party, national, and religious business. All helpful or harmful movements were either first conceived in these centers, or else were outrightedly born there. In New York, tailor Ghoomrigian’s store, especially its back rooms, had for a long time been a gathering place for Armenian personages, for the swapping of visits or ideas. Ghoomrigian’s had achieved a reputation for being a community hotbed. Certain conservatives had dubbed it the new “Oven of Galata.”

This broken down, wooden one-story structure was not one of the boasts of wealthy and beautiful New York. Ghoomrigian would needle out his livelihood in the front of the store while, in the black nest that represented the place’s rear, alas, the “nationalists” were totally unable to make a living out of their incessant chatter and pen-pushing.

One corner of the back of that store was closed off by a curtain hiding a decrepit bedstead, on which many of New York’s penniless (now people with quite a few pennies) would spend half-sleepless nights. Near this opaque cave were heaped one to two piles of coal. To some, the fuel was there simply to filter out the air of the place. There was also a row of tailoring benches, which, during the day, served the purpose for which they were exactly meant, while at night, they served another purpose—to provide luxurious beds on which many of us slept on many occasions. And right in the middle of all this there stood a stove with its belly red hot summer and winter in order to heat up the pressing irons of this master tradesman.

It was near that stove that Eginian and I sat that night and began discussing the eternal issue—the publication of a newspaper.

“I’ve already told you,” Eginian said, “that the ‘mother’ matrices for Armenian type are available at an American foundry.”

“Then,” said Ghoomrigian, “all that is needed is a sum of money to buy the Armenian type—the ‘daughter’ of the ‘mother’—and get to work!”

A few days later, with a capital of only about $300—which we extracted from a few personal acquaintances we named Ghoomrigian “treasurer,” and Eginian editor, servant, and typesetter and started publication of our Tigris. We produced two to three copies of this publication in Ghoomrigian’s other equally cavernous store on 42nd Street, and then transferred our operations to the rear of the now historic store on 4lst Street which, then, was to become the manager of Armenian-American journalism—the birthplace of the Hairenik.

We distributed 2,000 fliers among the Armenian communities announcing our publication. If we did not receive in return 2,000 “green sheets,” we succeeded in drawing to us a solid army of freeloading readers. At last, the editor had the satisfaction of reading his own newspaper into which he had inserted the enormous reams of world and local news he had so solicitously provided…

The newspaper Yeprad wholly dried up before the exuberant disaster that was to be Tigris. In suspending publication of his own organ, Hayk’s Soctor announced that “my publication will be resumed in April.” But the newspaper had had its cycle. It never appeared again.

There were many who were quite satisfied with all this. But there were a few—members of political parties—who had begun to mull the matter of the newspaper. They envisioned a party organ which would serve as a sort of half-official “mouthpiece” of the party. Using my position as a pretext, the Dashnaktsakans started submitting ARF propaganda articles and even “Droshakakan poetry” to the editor of Tigiris. On their own parts, the Hunchaks, regarding Eginian as their open sesame, started sending in anti—Dashnaktsakan encyclicals to us. And thus, one day the tumult reached that point when the unforgettable A. Levonian “started drawing up the four corners of the curtain on A. Arpiarian’s treacheries.” It was inevitable, of course, that K. Chitjian and G. Papazian “pulled down the four corners of the same curtain” in the next issue of Tigris.

A remedy had to be found to all this.

One day, the late and lamented ARF fieldworker, D. Vahanian, who was then in Worcester, sent A. Levonian to me bearing the Western ARF Bureau’s unfavorable answer to a petition we had rendered the organization (for assistance). Levonian told us that our fellow Dashnaktsakans abroad would not aid us financially, but would send us a shipment of type should we start publishing a semi-official newspaper in America.

At this, the incomparable Levonian coursed from Boston to Worcester, Lawrence, Lynn, Haverhill, and thereabouts. In New York, New Jersey and Providence, politically minded ARF members “huddled head to head,” and, one day—a beautiful spring day—in Providence, a few “selected” members heard Marcus Der Manuelian read to them the first editorial of the Hairenik. Although the newspaper was not yet in existence, its first “editorial” had been pre-published!

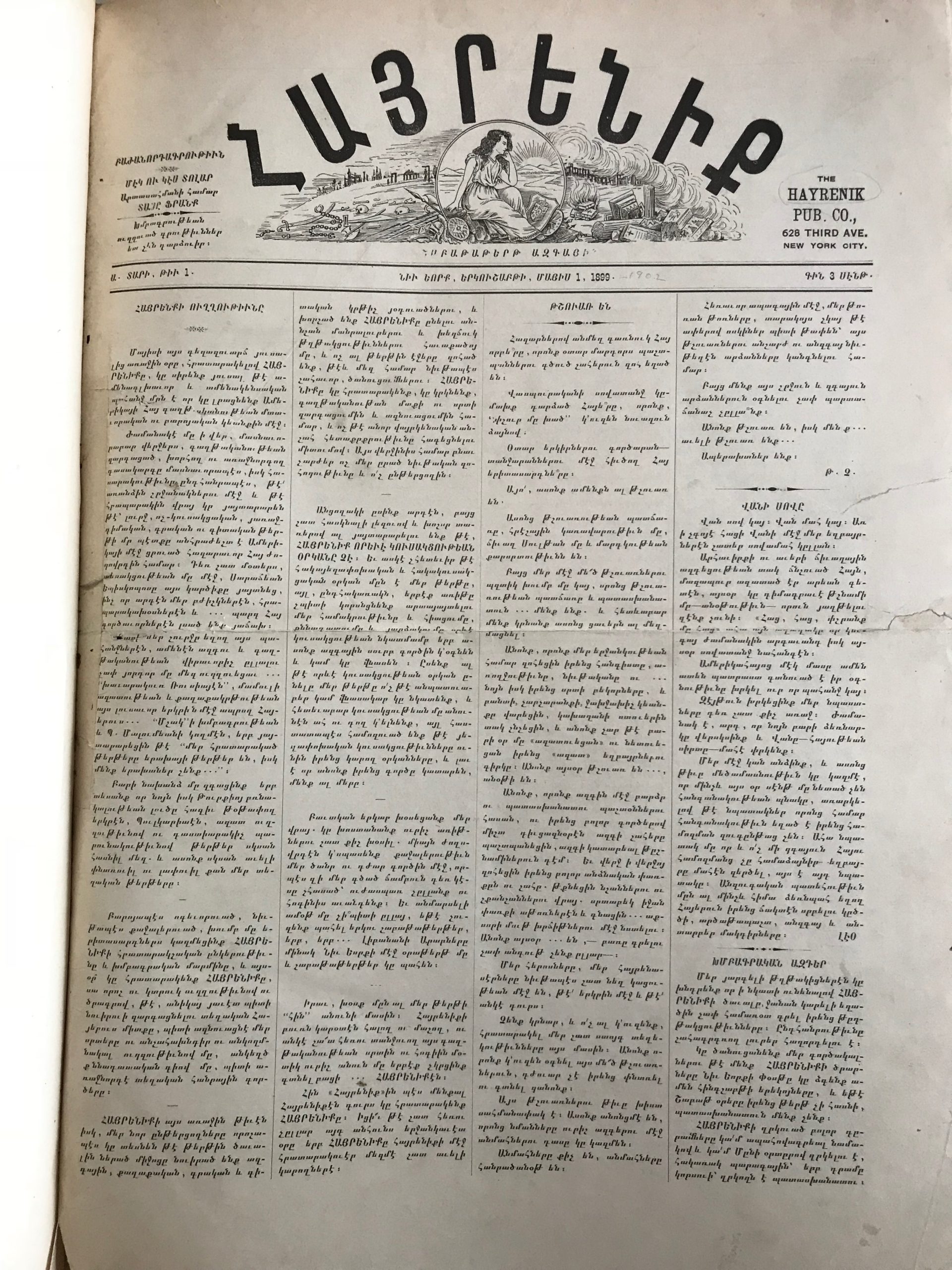

The first issue of the Hairenik saw the light of day on May 1, 1899. It is totally necessary to say that that first historic issue was produced in the rear of Ghoomrigian’s store.

There was an editorial, but there was no editor. There was a newspaper, but there was no money.

The New York Committee of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation must be given the honor of being recognized as the earliest initiator of the Hairenik—that is, all glory to Vart Manoushag. the industrious M. Minasian, M. Ferahian, Baghdasar Yeghpayr (Hagi), the“melancholic” Mr. Chakour, the spirited D. Kiupelian, as well as to such sympathizers as the Ghoomrigians and K. H. Tashjian, of Philadelphia. All glory to such as Providence’s Marcus Der Manuelian, T.Jelalian, Dzaghig and the late Aslan; to Caro of Haverhill and K. Kaloustian of Lawrence; to Alipounarian, Kelemkarian, Boyajian, the Barsamian brothers and Berberian, all of New Jersey; and to H. Chakmakjian of Stamford, Connecticut, and others whose names we have unfortunately forgotten. All these individuals participated financially and morally in the birth of the Hairenik.

Through the efforts and sacrifices of members and friends, the ARF Convention, held that year in Boston, discussed the issue of the Hairenik and directed the Central Committee to buy a $100 share in the company. And so the capital assets of the company stood at a figure over $200!

One night, we attended a meeting of members and sympathizers in Marcus Der Manuelian’s room in Providence. We found that we had to provide an official editor to the fledgling newspaper. I was elected to that servitude. And so I returned to New York endowed with the following offices—editor, publisher, senior typesetter, secretary for all important and impossible pieces of correspondence, proofreader, compositor, folder of over 1,500 copies of each issue, addressor and transporter of copies of each issue to the post office for mailing. Also, I was to perform the miracle of meeting expenses, balance the books for a short while, and, in the long run, pay salaries, etc.

And so it was that on May 1, 1899, on a very historic day, the first issue of the new Hairenik came off the press.

Within a period of four to five weeks, we had won many friends among the reading public. The liberal minded youth especially rallied to the publication and helped it root itself. At the same time, we were honored by the opposition. Almost the entire adversary “fraternity,” including the cowled and hooded clergy, as well as the Hunchaks and the Reconstructed, started railing at us.

One evening, Archbishop Mousegh, in addressing a meeting called in New York to elect a church trustee board, fulminated that the editor of the Hairenik and his cohorts were unbelievers—were not worthy of taking a hand in spiritual and church matters. One Tavshanjian, the chairman of that meeting, offered his friend, the Archbishop, by glossing over the matter, for he knew that otherwise the Armenian community of New York would be subjected to internecine quarrels which could very well approach bloodletting.

The clerics were growling because the Hairenik was publishing translations of lngersoll’s writings. Professor Mangasarian was sending these translations to us.

The Reconstructed were furious at us for daring to criticize Minas Cheraz for printing, in his Armenia organ, lengthy disquisitions informing foreign circles of Arpiarian’s “filthy intrigues” during the period of the existence of the United Association. We found it simply odd and harmful that Cheraz had found it suitable to introduce this purely internal Armenian matter in French for the reading of the French. We suggested that he terminate this series written in a foreign language and for him to say what he had to say in the Hairenik.

The zealous bards of stygian darkness openly detested the newspaper too because a handful of about a half a dozen women were working for the Hairenik. A certain woman, who described herself as an exponent of “Armenian Life,” even opened a public quarrel with a “common” woman.

The Hairenik had scarcely published two to three weekly issues when news arrived of the terrible events in Vasbourakan (Van).

The newspaper immediately called for financial assistance of the people of the stricken area and, within two weeks, the more heavily populated Armenian communities in the United States held fundraising meetings benefiting Van, and respectable sums were raised to that purpose.

If my memory does not deceive me, the fifth number Hairenik was devoted to the Van appeal.

I remember this event even more clearly because it was the occasion for a quite unusual request made of me by the valued Tovmas Jelalian of Providence.

“Adash,” my namesake wrote me, “I saw on the front page Hairenik pictures of Hairik, Aghtamar and Aikestan, but now please print some material telling us what to do. Send that paper to me as soon as possible so that I will be able to read what you have to say before our general meeting on the Van appeal to be held here in Providence this Saturday at Exchange Place. I would rather read to the people your directions than deliver a speech.”

In a hurry, with great difficulty, in the short time that I had, I was able to meet Tovmas’ request. We had devoted so much time and effort to finding the pictures we had used and making cuts of them for publication, that we had either forgotten or had not had the time to write a supporting editorial. I remember that incident very well. Then I saw that the forms of the next issue had to be bound within two hours, that printing had to take place, and that all the copies of the issue had to be taken to the post office on Thursday evening, if I were to meet Tovmas’ request.

Our beleaguered mind finally conceived the headline “Vasbourakan is Hungry” and its supporting subhead, “The Hearts of All Armenians are with Vasbourakan at This Time…”

After reading what we had printed at the meeting, Tovmas sent us his thanks and sentiments of esteem.

We had achieved an encouraging moral victory. We had won a little army of cash-on-the-line subscribers. But our financial future hung on the goodwill of those who were credit subscribers.

We started receiving from here or there small remittances, trusting each day that the postman would bring us letters containing other sums of money. We would with great anticipation each day open letters. Lo, one dollar would emerge from one envelope, two dollars from another…how happy we were, how complete our kef (joy) when we saw that once again the costs of producing still another issue had been realized!

But the soul-rending number of small back-due debts continued to plague us. . . until one day we received an evangelical letter from A. Levonian, which read:

“I have already sent you $25 of the $100 promised by the (ARF) Central Committee in consideration of the organ’s financial needs. The remaining $75 will be forwarded to you shortly.”

Our joy at this news was unbounded. We could now stand before Ghoomrigian with our belts fastened and feed him sums of five to ten dollars (against our debt to him). We stood there now in such a state of confidence, not inexperience, even by the European nations in the World War I period when they expected receipts of money promised them by the United States.

But fond hope! We waited and waited for the promised $75 to arrive. Our discouragement grew daily until, one day, we received a note from Levonian chiding us for not having acknowledged his letter which had contained a $75 money order!

It was clear that the sum of money had been sent to us but had somehow become lost in the mail. It was not until two months later that we received the money order through the post office—but what hardships we experienced until that money was in our hands!

Every time Ghoomrigian would bring up the issue of the debts owed him, we would answer, “Well, what’s the big deal? We too have monies owed us, especially since what we are owed is from the government of the United States, behind which stands the United States army and navy, which in turn guarantees the collection of just debts!”

And so, the day came when it was absolutely necessary for the Hairenik to find a somewhat capable typesetter. Such a man was found, but the fellow had the gall to ask a salary of nine dollars per week. We were able to revel in his presence, however for only a few weeks when, one day (an evil day for the editor because the tasks of editor and typesetter was to fall back on his shoulders) it suddenly dawned on us that Hairenik was the only paper under the sun which paid its editor four dollars less than its typesetter. We were forced to rectify this injustice. Its solution emerged from the ranks of the ARF in the person of Harutune Deveyan, who performed for a time, with great devotion I might add, the onerous duties of typesetter.

Deveyan told me that he had accepted the job because, “I felt the crisis so deeply. I thought that instead of expecting a fully healthy man to sacrifice himself at this job, I should rather sacrifice myself.”

Later, that poor lad, while on his way back to the Old Country, was to find his grave in Marseille…

Somehow or other, the Hairenik was able to carry on until one bad day it received its most telling blow. It was a Wednesday morning. On the previous evening, Harutune had all but put the next issue to bed, although some proofreading had to be accomplished.

We were due to write and typeset the editorial that morning, and twined forms would have to be sent to the printing shop that afternoon without fail so that distribution could start that same evening.

That morning, while walking to the office, I saw Harutune running towards me. He alarmingly told me that Ghoomrigian’s store had caught fire that night from a neighboring store and that he had seen with his own eyes our precious forms scattered around the water and debris.

Elbowing my way through the firefighters, I ran into the store and saw that the Hairenik had burned down in the intense conflagration.

I had quieted down when I found among what papers were left our $300 insurance policy. You can imagine the composure of the distant fellow members, especially of A. Levonian, when they heard of the fire.

Our insurance policy had just been taken out. I first struck off a wire to Providence and ran off to see K. Chitjian and Hagopian, who were at that time editing Tigris. I bumped into them in the elevator of their building and asked them to announce in their next issue what had happened to us.

Hagopian demanded payment for such an announcement, but Chitjian promised to place the news on the back page of the next issue.

Soon tidings of the fire reached all our friends. Our type had been damaged, and publication was suspended. There was, however, hope of new funding. We received $240 from the insurance company.

But often, benefits emerge from adversity. We were able to find a six by eight foot room in a building on 23rd Street, and there we recommenced operations—in “larger” quarters and with better type.

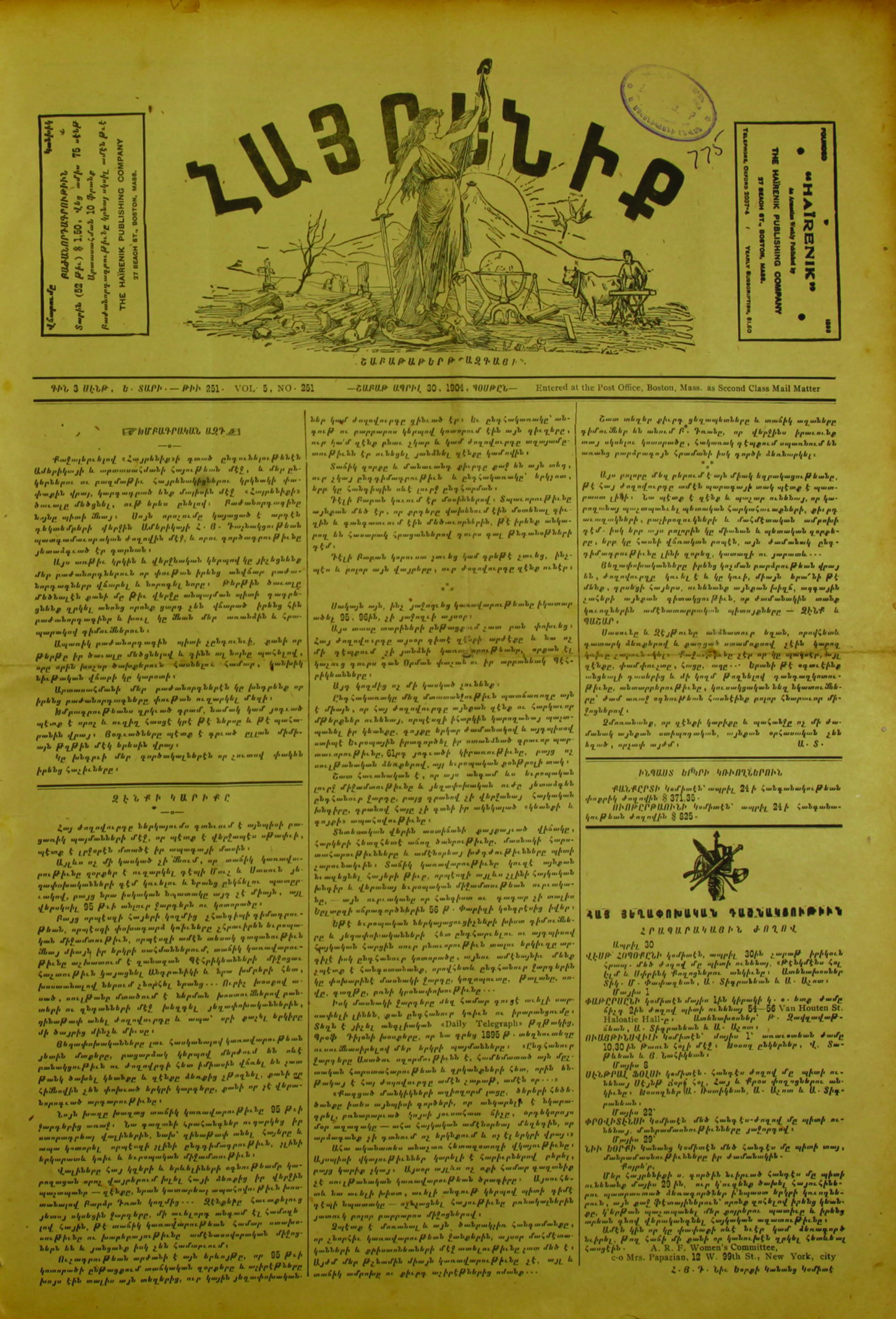

It was the logical conviction of most members of the party that the Hairenik ought to be moved to a place representing the center of the Armenian community of the United States. Boston came closest to answering that description. It was the center of a large concentration of party people and was the heart of the large New England Armenian community.

Mihran Minasian was named temporary editor of the publication, but the most suitable man to edit the organ arrived in the United States almost at that moment. He was Arshak Vramian who, right off the ship, was spirited by me to the ARF Convention held that year in Providence.

We were thrilled that O.K.T. (Vramian), the able editor of Constantinople’s Hairenik, would take over the paper for us very soon.

And so the Hairenik went to Boston and became the official organ of the ARF in America. It was to become America’s leading Armenian journal under Vramian’s guidance.

Through the succeeding years, Hairenik went from a weekly to a daily publication; and later, it was to add a great Monthly periodical to the Hairenik operation.

And we repeat here the fond hope of all Hairenik readers of our day that, someday, the Hairenik will be printed in our Hairenik (the fatherland).

The English translation of Charshafjian’s piece was originally published in the Armenian Review (May 1979, Vol. 32, No.1-125).

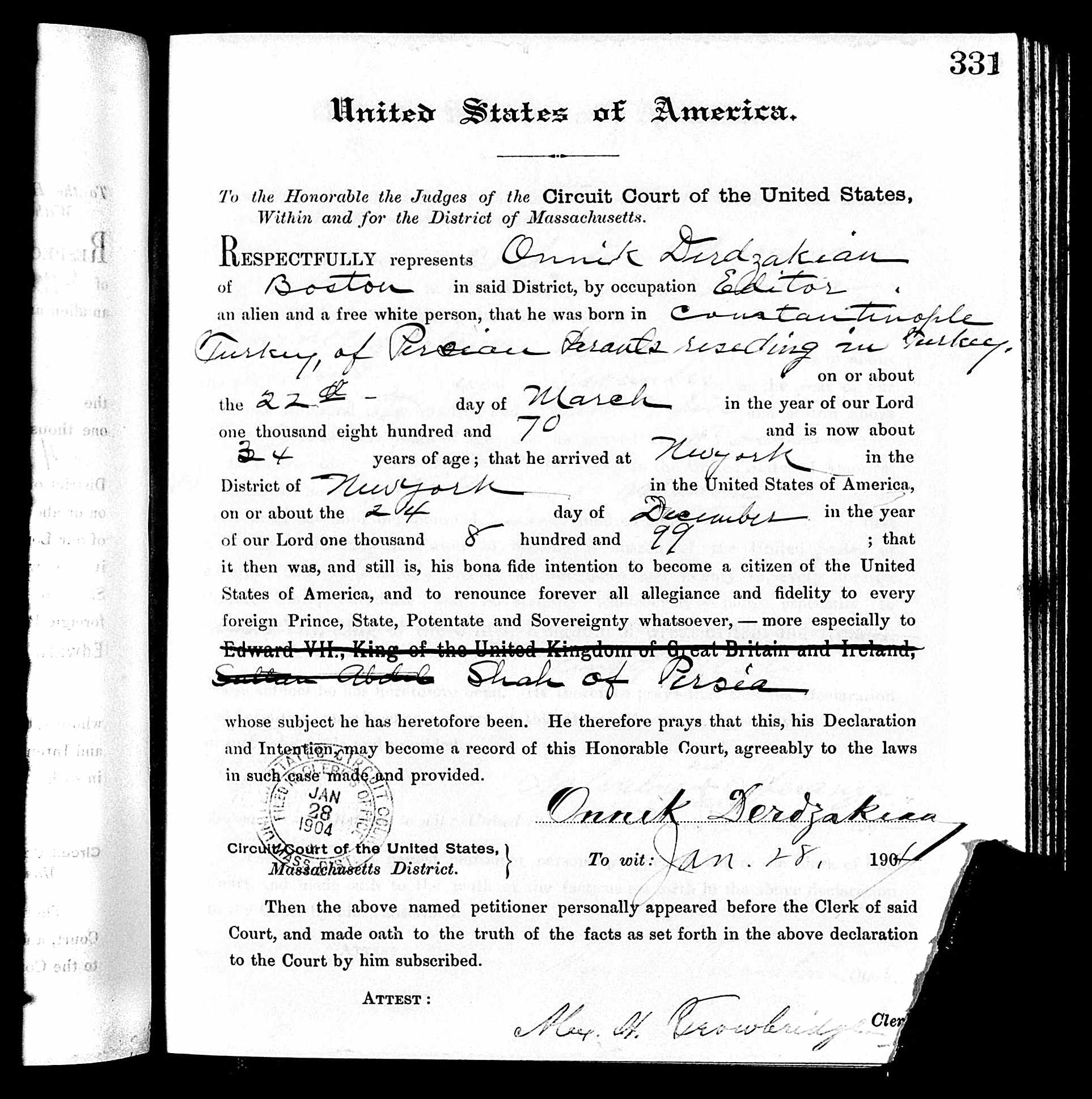

Tovmas Charshafjian was the founding editor of the Hairenik. He was born in Dikgranagerd in 1872, He first attended the local school, then the Berberian College of Constantinople, as well as Roberts College, from which he did not graduate. Instead, he left for London to pursue a degree as a medical doctor. Because of financial difficulties, he halted his studies and in 1895, found himself in America, where a large number of Armenians from Western Armenia had settled.

After his arrival in the U.S., he sought out a newspaper, for which he could work as a contributor. The father of Armenian journalism Haygag Eginian, who published a series of newspapers, including Arekag, Sourhantag, and Azadoutiun. Another was Tigris, for which Charshafjian worked for a time; but as with others of Eginian’s newspapers, for Charshaflian it too was bland and dull.

Consequently, Charshaflian and others felt the deep need for a paper such as the Hairenik. Charshafjian served as the first editor of the Hairenik, from May 1, 1899 to March 30, 1900.

During the last decade of his life, Charshafjian lived in illness. He passed away on Jan. 1, 1954, in Fresno, Calif.

Be the first to comment