By Gilda Buchakjian (Kupelian)

PARAMUS, N.J.—“Act, Pact, and Impact” was the title of a three-lecture event sponsored by the Armenian Missionary Association of America (AMAA) at the Armenian Presbyterian (APC) Church in Paramus on June 12. The event was in honor of Hrant Guzelian, the extraordinary hero of one of the most significant post-genocide rescue missions, on the occasion of the publication of the English version of his book, Youth Home of Istanbul: A Story of the Remnants’ Home Coming.

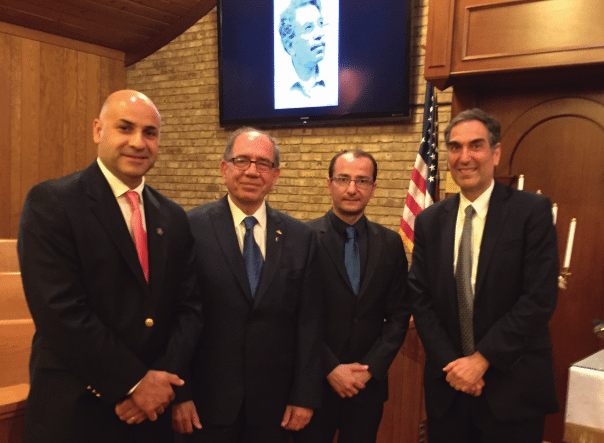

The three remarkable speakers were Zaven Khanjian, the executive director and CEO of AMAA, Rev. Berj Gulleyan, the pastor of APC; and Khatchig Mouradian, the newly appointed visiting professor at Rutgers University. The event was skillfully moderated by Peter Kougasian, Esq., AMAA Board member.

Guzelian’s work transcends the meaning of his moniker (“nice,” in Turkish) to the nth degree. He sought out orphaned children—10, 11, 12 years old—from Anatolia and brought them to Istanbul, to educate them as Christian Armenians. In his introduction, Peter Kougasian describes the “Youth Home of Istanbul” School (Bolso Badanegan Doun) in the basement of the Armenian Evangelical Church of Gedik Pasa: “not an ivy league school, but a school that lasted a sliver of time, together with its Summer Camp, Camp Armen in Tuzla (a suburb of Istanbul), which was established by Hrant Guzelian, created a legacy that has endured to this day.”

One of Hrant Guzelian’s protégés was Hrant Dink. Guzelian was well aware that the Turkish authorities would not reward him. He was incarcerated. Camp Armen was taken away by the Turkish government, and because of special interventions, Guzelian was deported to France in lieu of a harsher sentence.

Khanjian’s lecture began with the description of the current situation of Camp Armen. “On May 6, 2015, heavy demolition equipment belonging to a private company entered the camp and started the demolition of the structures on site. Young Armenian activists belonging to a group called Nor Zartonk (New Awakening) and a number of adults, part of over 1,500 rescued orphans who built and lived in the camp, rushed to the site, set up their tents, and stopped the process of demolition. Recently, Camp Armen has been on the forefront of Turkish, Armenian, and even world news covering Turkey.”

Khanjian stated that the AMAA takes pride in a “pious and God-loving Armenian called Hrant Guzelian” and the long-standing support that it has given to the “Youth Home of Istanbul.” He explained how Hrant Guzelian had gone to Anatolia in the early 1940’s as a soldier in the Turkish Army. There, he came across many genocide victims, “realized their misery, witnessed the deliberate erasure of centuries of Armenian civilization including many ‘Houses of God,’ was alarmed but was ‘mentally and psychologically ready’ to do something about it.”

Here is what Guzelian says at the end of the chapter covering his military service in the Turkish Army: “There are the good next to the evil, the fair next to the unjust: but what does it matter, when the overwhelming majority is evil? The state has been unfair, evil, oppressive, unfeeling, and biased. Envying our mores, instead of following with virtuous jealousy, learning and attaining high level, the Turk wanted to annihilate us, usurping, appropriating, insulting, and depriving us of our most basic rights, the language, the faith, the culture. Add a number of other events, which pained my heart for the crimes and injustice. I thought what can I do in some measure to do my share and be useful to the remnants of my nation?” And useful, he was.

Referring to the book, Khanjian said, “It should not be read for its literary merits. It will not win the Nobel Prize in Literature but it sure deserves a Nobel Prize in Human Rights and in the struggle for justice for all oppressed.”

In conclusion, Khanjian said, “Today the struggle continues and although the title of the property is demanded to be returned to the Armenian Evangelical Church of Gedik Pasa, this struggle has no denominational identity. It is an Armenian struggle and it will bring forth an Armenian victory.”

Rev. Berj Gulleyan admitted that initially he did not know who Hrant Guzelian was. He had heard from a friend that Guzelian was “humble but on fire.” It was after he read the book that he realized the importance of Guzelian’s legacy. Pastor Berj spoke about the impact of fathers on children, and of the extraordinary orphan Guzelian took under his wings—Hrant Dink.

“Justice apart from God is not possible,” he said, and elaborated on Guzelian’s passion: to seek the lost children and bring them home. Empowered by his love for God, Guzelian brought the boys and girls to a safe haven, to teach and nourish them. “We need good role models like Hrant Guzelian,” said the pastor.

“How can we continue Hrant Guzelian’s legacy? By remembering him and the impact he had on the children he saved. And on a practical level, never stop supporting schools overseas,” he said.

Speaking about Armenians in Turkey, Mouradian feels that “struggling collectively is very hard,” in an environment where Armenians have suffered from persecution and racism for a century. In this context, “Hrant before Hrant” was a phenomenon. “His commitment to justice, his own faith created a reality that did not match that of the typical Turkish Armenian’s.” The moment he started the school, he signed on to be potentially imprisoned and even make for his own demise.” Turkish authorities would fill each church with explosives and blow them all up except one monastery that stood in defiance. “The fate of individuals,” continued Mouradian, “was not any different.” Those Armenians that remained in Turkey are called “remnants of the sword.” “As we are losing our direct connection to the Armenian Genocide, and life in the old country, citizens of Turkey are discovering their connection, their grandmothers. Hrant Dink was instrumental; however, it was Hrant Guzelian who blazed a trail, one of the first,” he said.

Mouradian also spoke about the hidden, Islamized Armenians who “often with their courage, deep commitment to their heritage, to truth, have a lot to teach us.” As we think of the legacy of Hrant Guzelian, Mouradian urged everyone to commit and to learn from the dedication of all those who against all odds are finding a place in the ground, to shelter it, like Hrant Dink, and to make it a guiding light and look forward.

Peter Kougasian concluded the day’s program by saying that we have not “just come to reflect on our identity, we preserve an important part of humanity that links us to each other.”

Among the many attendees, predominantly Diaspora Armenians from the Middle East, an Armenian resident from Diyarbakir drew heartfelt applause. A reception concluded the event.

I recall that when touring AMAA sites in 1970, including those in Turkey, that we visited Camp Armen. I don’t know as I was told the importance of the camp then, but am impressed to learn and ‘revisit’ its importance now via recent news.

Guzelian is my family name, but I had not heard of Hrant Guzelian and his amazing work before. Thanks for this very informative and uplifting article.