Special Issue: Genocide Education for the 21st Century

The Armenian Weekly, April 20231

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

–John Adams, 17702

Almost 200 years after John Adams spoke the words quoted above, Hannah Arendt, in her 1967 essay “Truth and Politics,” reflected on a problem she identified earlier than most: “the extent to which unwelcome factual truths are tolerated in free countries they are often, consciously or unconsciously, transformed into opinions—as though the fact of Germany’s support of Hitler or of France’s collapse before the German armies in 1940 or of Vatican policies during the Second World War were not a matter of historical record but a matter of opinion.”3

Denial does not necessarily need to convince people to be effective: it inflicts sufficient damage by creating a spurious discussion that creates a haze of doubt around the facts. Facts may be stubborn, as Adams stated, but as Arendt understood, if you can confuse enough people about what the facts are, it is possible to reduce a set of facts to merely the status of opinion.

The American civil rights leader Medgar Evers is credited with saying, “You can kill a man but you can’t kill an idea.”4 (Evers was murdered in 1963 by a member of the Ku Klux Klan.) But the Ottoman Empire and subsequently the Republic of Turkey have tried, and in some ways succeeded, in having it both ways. First they killed the Armenians, and then they tried to kill the idea that they had killed the Armenians.

Turkey’s protégé state Azerbaijan has emulated its “big brother,” expunging the region of Nakhichevan of all evidence of Armenian existence, threatening Artsakh with annihilation while eradicating evidence of Armenians’ presence in the region, and, in effect, denying the existence of Armenia as such.5 Furthermore, subsequent to the writing of most of this article, beginning on December 12, 2022, Azerbaijan imposed a blockade on Artsakh, sealing off its sole connection to Armenia (and, thus, the world), creating dire conditions for the Armenian inhabitants of the region and, in effect, holding them hostage.6

Turkey and Azerbaijan are often aided and abetted in their contra-factual efforts by people who call themselves scholars, journalists and policy analysts who, sometimes knowingly, sometimes ignorantly repeat the counterfactual, denialist assertions that emanate from those states. While it is a universally accepted truism that the best way to combat ignorance is with education, and it is also frequently asserted and widely accepted as incontrovertible that education about genocide is the most effective means of preventing its recurrence as well as thwarting its denial, the facts on the ground suggest that this may be optimistic: the remarkable development and proliferation of genocide education in recent decades has not resulted in the elimination or necessarily even the marginalization of genocide denial.

One does not wish to suggest that education about genocide serves no purpose, nor that it can have no impact on genocide denial; on the contrary, it is essential. It is important to realize, however, that denial is not always, or even mostly, a product of ignorance, but instead is a strategy for producing a kind of ignorance. As denial and the propagation of “alternative facts” takes its place at the center of contemporary life, it is increasingly important to understand how it works and what it seeks to accomplish. It is there that education is desperately needed.

In 2019, after decades of Armenian-American advocacy, both the US House of Representatives (H.Res. 296) and the Senate (S.Res. 150) passed resolutions expressing “that it is the policy of the United States to commemorate the Armenian Genocide through official recognition and remembrance,” “reject[ing] efforts to enlist, engage, or otherwise associate the United States Government with denial of the Armenian Genocide or any other genocide,” and “encourage[ing] education and public understanding of the facts of the Armenian Genocide, including the role of the United States in humanitarian relief efforts, and the relevance of the Armenian Genocide to modern-day crimes against humanity.” On April 24, 2021, US President Joe Biden became the first president to issue a statement on Armenian Genocide Remembrance day that actually employed the term “Armenian Genocide.”7 In 2022, Mississippi became the 50th and final state to recognize the Armenian Genocide.8

These landmark occasions in the long struggle for US recognition of the Armenian Genocide follow other such acts of recognition elsewhere in the world and anticipate, one might suppose or hope, future instances elsewhere.

While these noteworthy acts of recognition by the US and other states and entities are in themselves important and contribute to the never-ending pushback against genocide denial, they do not signal that efforts to deny the Armenian Genocide are in retreat. Turkey’s official denialist stance remains unchanged and efforts to push its narrative in academic, journalistic and think tank circles are undiminished. Furthermore, just as Turkey and Azerbaijan have forged a strong strategic partnership exemplified by the catchphrase “One Nation, Two States” and enacted in the Turkish-facilitated Azerbaijani attack on Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) in 2020, they and those who support their efforts have common cause in crafting and disseminating denialist narratives.9 As historian Bedross Der Matossian has recently written, “denialists of the Armenian Genocide are not part of the past, they are still very active in contemporary academic circles. In addition to being preoccupied with their futile efforts at the dissemination of (mis)knowledge about the Armenian Genocide, they also are currently embarking on new projects to write a revisionist history that denies the historical ties of Armenians to the land of Karabagh and undermines their quest for self-determination.”10

In the aftermath of the 44-day war in late 2020 and the recognition by President Biden of the Armenian Genocide in April 2021, there has been an impressive outpouring of analysis and opinion pieces on matters relating to Armenia, Turkey and Azerbaijan—impressive in quantity, if not always in terms of quality. All too often these have been highly selective and misleading in their presentation of facts and are distorted by, if not examples of, denialist discourse.

I would like to take a look at three pieces that appeared in prominent, internationally known outlets, Sinan Ülgen’s “Redefining the U.S.-Turkey Relationship” (published on the Carnegie Europe website), Hans Gutbrod and David Wood’s “Turkey Will Never Recognize the Armenian Genocide” (Foreign Policy, June 14, 2021), and Ghaith Abdul-Ahad’s “Each Rock Has Two Names” (London Review of Books, June 17, 2021), before briefly turning to a very recent book publication, The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Historical and Political Perspectives (2022), edited by Michael M. Gunter and M. Hakan Yavuz, and considering some of the fruits of Azerbaijan’s efforts to assert itself in the sphere of western academia.11

A Classic Strategy: The Armenian Genocide as “Controversy”

“Redefining the U.S.-Turkey Relationship” is the first publication in a Carnegie Europe series it calls the “Turkey and the World” initiative. The paper is authored by one of Carnegie Europe’s experts, Sinan Ülgen, a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe in Brussels and a former member of the Turkish foreign service.

Contained within this lengthy working paper is Ülgen’s discussion of the impact of President Biden’s statement of April 23, 2021. Ülgen’s overall policy discussion and recommendations are beyond the scope of this discussion. They are summarized by Carnegie Europe thusly: “To fix their troubled relationship, the United States and Turkey should take gradual, concrete steps that build confidence and focus on common agendas.” As an analyst, he is entitled to his views and to share his perspective.

However, when Ülgen briefly provides historical background for the discussion of what he calls “the Armenian Question” he defaults to repeating lines from Turkey’s official denialist script. This may be expected from a career Turkish foreign service officer—indeed, it may be part of the job description; but it ought not to be acceptable from a Carnegie Europe-certified expert.

We must be clear about what denial of the Armenian Genocide is. It has shifted from an untenable position of total denial—no Armenians died, it is all a fabrication—to acknowledging and perhaps even expressing regret for the loss of Armenian lives during a time of general suffering but rejecting the existence of a coordinated effort to destroy Ottoman Armenian existence and thus denying the applicability of the term genocide. The shift has occurred not because the Turkish state is moving towards recognition of the Genocide but because it has found that “softer” denial is actually more effective. As Jennifer Dixon has argued, “while the narrative shifted to acknowledge some basic facts about the genocide, Turkish officials simultaneously took steps to more effectively defend core elements of the state’s narrative. Consequently, movement in the direction of acknowledgement was accompanied by the continued—and arguably strengthened—rejection of the label ‘genocide.’”12 What all styles of denial have in common is the repudiation of the extensive documentation and scholarship on the Armenian Genocide.

Ülgen’s use of the phrase “Armenian Question” is in itself telling. In historical discourse, the Armenian Question refers to the international debate between approximately 1878 (the end of the Russo-Turkish War) and World War I over the treatment of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. In more recent parlance, of which Ülgen’s use is an example, the phrase stands for the so-called debate over how to describe and characterize “the events of 1915.” The Ottoman and then Turkish Republican solution to the historical Armenian Question ultimately was to render it moot through genocide. The Turkish state’s answer to the latter-day “Armenian Question” is the eradication of historical facts—or at least demoting them to the status of opinions, much as Arendt described.

Ülgen’s presentation exemplifies the more sophisticated end of the genocide denial continuum that has emerged over the last three decades, which acknowledges the tragic loss of Armenian lives but insists that the entire topic is fundamentally controversial and reducible to a he said/she said dispute between two sides: “Turks” and “Armenians.”

“The proper characterization of the large-scale massacres committed against the Armenians under Ottoman rule remains controversial to this day,” Ülgen asserts, without explaining the origin of this spurious “controversy”—more than a century of Ottoman and Turkish denial—or conveying the lack of controversy surrounding the characterization of the Genocide among experts. The suggestion that there is no consensus on the issue would be news to the International Association of Genocide Scholars, which has unanimously recognized the Armenian Genocide and called on the government of Turkey to end its denial campaign.13

Consistent with his professional background in the Turkish foreign service, he provides a distorted thumbnail sketch of the Armenian Genocide:

Beginning in 1915, the Ottoman leadership began to arrest, kill, deport, and forcibly resettle the empire’s Armenian minority, in order to quash potential resistance or independence movements among the Armenian population. Armenians claim that these events amount to genocide. Turks, in return, claim that it was a forced relocation under the conditions of war, which ended tragically.

Ülgen has put forward a historical narrative not fundamentally different than that offered by the Ottoman Empire as the Armenian Genocide unfolded and then by the Turkish state and its genocide-denying apologists: the Ottoman leadership acted reasonably to counter a legitimate threat represented by its Armenian population. The end result may have been tragic, but Armenians brought it on themselves. It was not genocide, and it is only Armenians who claim that it was. Furthermore, “Turks,” which presumably means all Turks, claim otherwise. There are no discernible facts: merely competing “claims.”

Such an account is indistinguishable from the current official narrative by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which states that “the Ottoman Government ordered in 1915 the Armenian population residing in or near the war zone to be relocated to the southern Ottoman provinces away from the supply routes and army transport lines on the way of the advancing Russian army. Some Armenians living away from the front, yet were reported or suspected to be involved in collaboration, were also included in mandatory transfer.” It also notes, with what is perhaps meant to be exemplary sensitivity, that “Loss of life, regardless of numbers and regardless of possible guilt on the part of the victims, is tragic and must be remembered.”14

The genocidal intent of the Ottoman authorities and the genocidal consequences of their actions are amply documented and described in a large body of scholarship. That Ülgen never mentions the existence of such materials does not speak well for his status as a Carnegie Europe expert. Indeed, the only time he acknowledges the concept of “a consensus within the academic community about the nature of these events,” is to question its existence. Such an approach is in keeping with the arguments made by extreme nationalist Doğu Perinçek (supported by the Turkish government) before the European Court of Human Rights, in defense of Perinçek’s right to deny the Armenian Genocide, which he had called “an international lie.”15

Perinçek and Ülgen embody the full spectrum of Turkey’s denial of the Armenian Genocide. The former is outlandish, aggressive and deliberately offensive. The latter is suave, polished and steeped in the language of Davos diplomacy. They seem to be polar opposites. Yet they approach “the Armenian Question” with the same goal—to deny the factuality of the Genocide.

Ülgen recounts the Turkish government’s reaction to international recognitions of the Armenian Genocide, stating that “it regards many of them as politically motivated,” and that “many Turks believe that the West was singularly interested in the fate of Christian Armenians but totally aloof to the large-scale tragedies that affected Muslim Turks in the same period.”

It is apparent that, although he declines to say so, these staples of Turkey’s denialist narrative which Ülgen presents as representing the positions of “the Turkish government” and of “many Turks” are also his own views.

Following President Biden’s April 23, 2021, statement, Ülgen took to Twitter to express his disapproval, complaining: “The reason why Turkish people are reactive to Western pontification about the events of 1915 is that these statements are singularly focused on the fate of Christian Armenians. And include no empathy with the Muslim Turks who also perished in great numbers.”16

He also repeated via Twitter the counter-statement issued by the Istanbul-based Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies (EDAM), of which he is the chairman.17 Although EDAM is, purportedly, an independent entity, on this subject its position and the position of the Turkish state are identical. The statement reads, in part:

US President Biden’s remarks yesterday on the qualification of the tragic events of 1915 as a genocide are fully in contradiction with these norms of responsible statecraft. A head of state should not have passed judgment on this controversial period of history in such blatant disregard to the principles of international law. In addition, these remarks are likely to undermine many ongoing positive dynamics that would have helped to reach a better understanding of this large scale tragedy. Over the past years, the Turkish government has recognized the enormity of the human suffering caused by the fateful decisions of the Ottoman leadership in 1915. Ankara has also expressed its regrets for the consequences of these actions. Secondly at present Turkish society is having a debate on the nature of these atrocities. International pressure can only stifle this domestic debate. It is up to the citizens of Turkey to freely shape their opinions. The cause of freedom of expression will not be served by such international pontifications.18

We do not know if Ülgen was the author of this statement, but his Twitter feed would suggest that he regarded the statement as conveying his own thoughts. At any rate, the ideas expressed by EDAM are entirely consistent with Ülgen’s own presentation: facts as such are not part of the discussion, only a “debate” and “opinions.”

Ülgen’s Twitter feed and the EDAM statement are part of the public record. Nevertheless, Carnegie Europe granted him space to present his denial in the guise of expert policy analysis.

Some have previously expressed frustration with Carnegie Europe’s highly problematic writings on matters relating to Armenia, Turkey and the Armenian Genocide, and its reflexive and inadequate response when criticisms have been offered.19 Ülgen’s work is significantly worse still with its uncritical adoption of official Turkey’s language of genocide denial.

While the article carries the caveat that “Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees,” that does not grant it carte blanche to irresponsibly disseminate counter-factual state propaganda. An organization with Carnegie Europe’s reputation ought to be capable of distinguishing facts from fiction, history from state propaganda.

An Exercise in Moral Hubris and Missing the Elephant in the Room

Hans Gutbrod and David Wood’s “Turkey Will Never Recognize the Armenian Genocide” is a remarkable exercise in moral hubris as the authors dispense their bromides and presume to lecture Armenians on how they should “commemorate the past in an ethical manner.” What is most noteworthy about the piece are its elephant-in-the-room-sized omissions which inevitably skew the discussion the authors are attempting to engage in.

The authors, who are professors at Ilia State University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and Seton Hall University in New Jersey, respectively, propose to address “the moral dimensions of an Armenia-Turkey détente,” warning that “a focus on achieving justice alone—through unilateral action or external arbitration—may provide a sense of validation to victims, but it can also fuel resentment, sour relationships, and lead to future violence.” They argue that “the Armenian and Turkish governments should work to reframe the Armenian genocide—and the wider suffering that accompanied the downfall of the Ottoman Empire—as a shared history” and even recommend that “Washington could fund research into Turkish and Armenian sentiment on the Armenian genocide to explore the contours of belief in more depth to transcend the ongoing standoff.”

On one point, at least, I am fully in agreement with the authors: Turkey will likely never recognize the Armenian Genocide; at least, it is hard to imagine that day coming. They are mistaken, though, in asserting that the only point of international efforts to gain recognition of the Armenian Genocide is to compel Turkey to do likewise. As a citizen of the United States, I do not think it is unreasonable to want the stance of my government to reflect the reality of the history of the Armenian Genocide, as well as other historical realities, and not to aid and abet Turkey’s denial.

Efforts to gain international recognition, while not necessarily an end in themselves, usefully highlight the absurdity of Turkey’s denialist stance. Why is that useful? Because—and it is simply incomprehensible that the authors do not mention this important fact—Turkey not only does not recognize the Armenian Genocide but also it actively, vehemently, and aggressively denies it; and not just within its own borders but also abroad, wherever and whenever possible, in a multitude of ways.

There is a significant body of scholarship as well as general commentary dating back to the 1970s on the topic of Turkish denial of the Armenian Genocide. It is hard to believe that two serious-minded scholars could be unaware of this or, if aware, why they chose to omit mention of it. Likewise, it is difficult to see how a discussion of how to “commemorate the past in an ethical manner” can occur without taking the issue of Turkey’s denial into account. Such omissions and lapses do great harm to the credibility of their presentation.

Furthermore, the authors fail to take into account the vast power discrepancy between the two nations, both historically and currently. Turkey, with its huge population and military capacity, has for some three decades imposed a blockade on Armenia; the tiny remaining Armenian population in Turkey has lived in constant fear of discrimination or violence for a century; and Ankara, at minimum, was Azerbaijan’s indispensable ally and provider of weapons for its war of aggression against Armenians in 2020. These facts are not mentioned by the authors. While they rightly decry the “petty triumphalism of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev” following the war, no mention is made of Ankara’s own “petty triumphalism.”20

Gutbrod and Wood call on Armenians and Turks, or perhaps Armenia and Turkey, to “reconcile.” Reconciliation implies a restoration of friendly relations after a dispute. While, historically, there was not always an intractable state of bloody conflict between Armenians and Turks, neither was there a state of relations at an earlier time—say, prior to the Armenian Genocide—which it would be reasonable to expect Armenians to want to restore.

The entire discourse of “Turkish-Armenian reconciliation,” as it has been framed mainly by European and American policy makers, and never more so than in Gutbrod and Wood’s presentation, positively reeks of first-world paternalism. As a white American, I would not have the temerity to call on Native Americans or African Americans to set aside seeking justice in order to “reconcile” with white Americans or to urge them to focus instead on highlighting the many good white people who opposed slavery or the annihilation of the indigenous population.

Indeed, such an analogy is not strong enough. More apt might be counseling Native Americans or African Americans to seek reconciliation with white Americans while the government openly and unapologetically denies its historical crimes and embraces white supremacism and neo-colonialism (a scenario which is, alas, not as fanciful as one might wish) or urging Jews to reconcile with a Germany that still denied the Holocaust. Such recommendations would be, one hopes, dismissed out of hand and seen as what they are: attempts to solve problems by coercing a victim group into abandoning its rights.

All too often we have seen the language of reconciliation deployed in the service of denial by stronger parties and the use of a so-called “reconciliation process” as a tool to defer any proper recognition of or redress for historical crimes. An insistence on the facts of the Armenian Genocide—by scholars, by activists, by governments—is seen as counterproductive, if not an act of aggression. That is, reconciliation is deployed as one more weapon to beat back acknowledgement of the historical record and consequences that might arise from such an acknowledgement, and a never-ending “process” fosters the illusion of forward progress.21 The dangling carrot of “Turkish-Armenian reconciliation” has become a version of the cruel ploy pithily articulated by Ralph Ellison to encapsulate the African-American experience in his novel Invisible Man: “Keep This N—– Boy Running.”

A secondary sense of “reconciliation” is the process of bringing into harmony two different ideas in such a way that they are compatible with each other. To that end, we might ask: “Is there any way to reconcile the Turkish state’s narrative of ‘the events of 1915’ with the historical record?”—for this appears to be what Gutbrod and Wood have in mind by “refram[ing] the Armenian genocide—and the wider suffering that accompanied the downfall of the Ottoman Empire—as a shared history.” Even a casual reading of Turkey’s official historiography and the work of those who promote it abroad must lead to answering this question in the negative. The only way forward is for Turkey to enter into the world of historical facts rather than state-manufactured historical fiction. Gutbrod and Wood’s recommendations do not point in that direction.

What is needed is an entirely new Armenian-Turkish relationship founded on the realities of history and based on equality that grants redress for previous wrongs to the maximum extent possible. This does not appear to be what Gutbrod and Wood are advocating, nor does it appear to be a likely prospect given the political realities on the ground. Unfortunately, by calling for a “redescription” of history “that various sides can live with” and suggesting that an inconvenient genocidal history can simply be “reframed,” they are granting Turkey license to continue its efforts to rewrite history and victimize Armenians.

Each Rock Has Two Names, But It Is Still a Rock

In “Each Rock Has Two Names” Ghaith Abdul-Ahad provides an uneven mixture of insightful commentary, tenuous arguments, and false equivalences about the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict. Painting with a broad brush, he states that “in both Armenia and Azerbaijan, writers constructed an ethnonational narrative that aspired to negate the existence of the other country, or at least to assign it the role of newcomer in the region.” The comparison, and the equation that it suggests, is fundamentally flawed.

While some historians in Armenia have indeed written problematic “ethnonational narratives” which warrant criticism, they have not, for example, systematically expunged references to Azerbaijan and Azerbaijanis from republished historical sources, in stark contrast with Azerbaijani academicians, who have excised Armenia and Armenians from such publications for several decades22 even as thousands of Armenian historical monuments have been destroyed within Azerbaijan. Criticism of the work of Armenian historians is certainly fair game—and calls for specifics rather than generalities—but the two cases are not comparable in any meaningful way.

Presumably by way of advancing this critique, Abdul-Ahad states that “Armenian writers pointed to Armenian churches and monasteries in Karabakh as proof of an uninterrupted presence in the area” and “dismissed the term ‘Azerbaijan’ as a modern political label.” But it is not only “Armenian writers” who have noted the ancient and uninterrupted Armenian presence in the area; it is not an “ethnonational” assertion nor an opinion but is simply a fact of which any historian or expert on the region must surely be aware. The suggestion that pointing out the obvious and indisputable fact of the evidence for ancient and uninterrupted Armenian presence in Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) is “nationalistic” is no more helpful or true than saying that the argument that vaccinations help combat Covid-19 is “liberal.”

Similarly, the use of the name “Azerbaijan” for the area comprising the current-day state of that name (as opposed to the region of Iran south of the Arax/Aras River that has been known as Azerbaijan from time out of mind) does not pre-date 1918. This is essentially a historically accurate statement, whether or not it is also uttered by nationalists.

Abdul-Ahad rightly identifies as “specious” the elaborate and preposterous fiction of Azerbaijani historians that modern Armenians “had erased ancient inscriptions and claimed monuments as their own.” Yet the unwarranted conclusion he draws is that “two peoples could look at the same building and each see in it what they wanted to see”—a curious and unhelpful equating of (or inability to distinguish between) reality and fantasy. Surely there is a difference between Armenians (and non-Armenians) looking at Gandzasar cathedral and identifying it as an Armenian church and Azerbaijani assertions that it is actually a Caucasian Albanian (and thus proto-Azerbaijani) edifice. Equating these two “positions” is an absurdity and may suggest that the person making the equation is either incapable of or unwilling to distinguish history from state propaganda.

Finally, Abdul-Ahad and one of his sources, analyst Phil Gamaghelyan, present a decidedly problematic view of Armenia-Turkey-Azerbaijan relations. Abdul-Ahad writes: “At a time when Turkey itself was at last taking steps to acknowledge this part of its history—decriminalising discussion of the genocide, allowing books to be published addressing all aspects of the late Ottoman period, holding commemorations in Istanbul and Ankara—it was in Azerbaijan that denialism flourished.” It is true that genocide denialism in Azerbaijan has flourished; it goes hand in glove with the overall negation of any and all things related to Armenians. It is, however, absurd and insupportable to say that because a small number of courageous individuals in Turkey were addressing the Genocide and holding commemorations that “Turkey”—as a state—was “taking steps to acknowledge this part of its history.” It is, indeed, a form of denial to say, as Abdul-Ahad does, that “More recently, however, Turkey returned to a denialist position.” Turkey has never left its denialist position, even if some Turks have.

Additionally, Gamaghelyan refers to the dangerous “Armenian nationalist narrative that Azerbaijan and Turkey were one and the same.” But of course it is not “Armenian nationalists” who have formulated the idea of Turkey and Azerbaijan as “one nation, two states”: it is Azerbaijan and Turkey who have devised and embraced this description.23 It is Azerbaijan and Turkey who put it into practice during the 44-day war of 2020, when “Turkey’s army-building capacity was clearly one of the leading factors contributing to Azerbaijan’s victory.”24 It was Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev who jointly celebrated the war’s outcome, which Aliyev called “an example of our unity, our brotherhood.”25 The June 15 Shusha Declaration further cemented this—if further cementing was needed.26

While Abdul-Ahad is right to look critically at how facts are used to advance various political (and perhaps nationalistic) agendas, be they Azerbaijani or Armenian, at key moments he fails to differentiate fact from fiction while doing so, presumably out of a desire to present a “balanced” picture.

Unpacking the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict requires identifying the harmful roles played by nationalist narratives, but the process is not aided by placing fact and fiction on the same footing as Abdul-Ahad too often does. Each rock may have two names: but if one side calls the rock a rock and the other insists that the rock is actually a tree, can we not at least agree where the problem lies?

“A comprehensive overview of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict”?

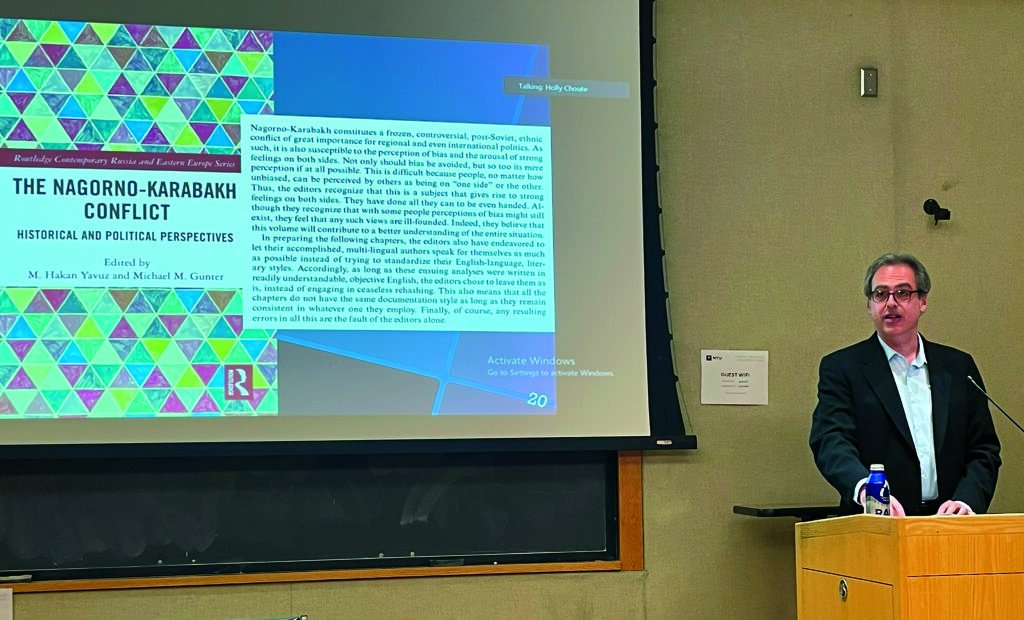

In late 2022 an ostensibly scholarly book appeared, The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Historical and Political Perspectives (Routledge, 2022), edited by M. Hakan Yavuz and Michael M. Gunter. Considerations of space preclude a lengthy discussion of the ongoing contributions of Yavuz and Gunter to the denial of the Armenian Genocide; I have already done so elsewhere, as have others.27 Suffice it to say that they have long been in the forefront of efforts to conjure an academic controversy about “the events of 1915.” It is this background, rather than any training in or expertise on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, that appears to have placed them in a position to extend their reach to editing a volume on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The editors make the grandiose claim of providing “a comprehensive overview of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the long-running dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Armenian-majority region of Azerbaijan.” Caveat emptor.

The editors provide a bathetic preemptive apologia as a preface, stating their deep sensitivity to the fact that the subject of the book is

susceptible to the perception of bias and the arousal of strong feelings on both sides. Not only should bias be avoided, but so too its mere perception if at all possible. This is difficult because people, no matter how unbiased, can be perceived by others as being on “one side” or the other. Thus, the editors recognize that this is a subject that gives rise to strong feelings on both sides. They have done all they can to be even handed. Although they recognize that with some people perceptions of bias might still exist, they feel that any such views are ill-founded. Indeed, they believe that this volume will contribute to a better understanding of the entire situation.

In the ranks of overdetermined protestations of impartiality, this ranks with Gunter’s own almost comical assertion in the preface to his 2009 Armenian History and the Question of Genocide that “Given the ‘received wisdom’ on the Turkish-Armenian issue, some will argue this book is a Turkish apology. It is not!”

Such reassurances are far from convincing.

It will have to be the task of other writers and reviewers to unpack the historical distortions larded into the 452 pages of The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. For the purposes of this discussion, it will be enough to note that the book’s primary task of presenting an account of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict that aligns with Baku’s preferred narrative is fully compatible with the long-standing efforts of the editors (and at least some of the authors) to cast all possible doubt on the Armenian Genocide. The book is replete with references to “genocide” in scare quotes, the “so-called Armenian Genocide,” “genocide allegations,” “claims of genocide,” and so on, which are a “natural” and synergistic companion to the book’s main objective.

In fairness, one must note that co-editor Yavuz is not entirely a newcomer to the world of pro-Azerbaijan, anti-Armenia activity. Of particular note in this regard is a special issue of the Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs (or JMMA, vol. 32, no. 2, June 2012) co-guest-edited by Adil Baguirov and Umut Uzer. According to the journal’s editor-in-chief Saleha S. Mahmood:

When we were approached with a proposal to dedicate a Special Issue of JMMA to one of the world’s ongoing, unresolved and perhaps now a ‘forgotten’ conflict, that of Nagorno Karabakh in the Caucasus, I was not quite sure if we can have the richness and variety in form and content that characterizes each issue of our Journal. Encouraged by Associate Editor, M. Hakan Yavuz, who connected us with the two guest editors of the proposed issue, Umut Uzer and Adil Baguirov, we took on this challenge.

Mahmood is effusive in his praise of the issue’s articles, concluding that they “all make for fascinating reading,” which is true but probably not in the sense that he means it.28

Adil Baguirov not only guest edited the issue but also authored the first article, extending traditional denialist rhetoric to a more recent issue in “Nagorno-Karabakh: Competing Legal, Historic and Economic Claims in Political, Academic and Media Discourses.” The guest editors declare at the outset that “[i]t is clearly evident that the NK conflict has been generally misunderstood, ignored or distorted as well as understudied in academic circles as well as exploited for political purposes.” It soon becomes clear that what they mean by this is that the NK conflict has been generally misunderstood, ignored or distorted as well as understudied in academic circles as well as exploited for political purposes by Armenians.

Baguirov is the co-founder of an entity known as the Karabakh Foundation (as is acknowledged in his contributor bio), of which JMMA Associate Editor M. Hakan Yavuz is also the only listed member of the Board of Trustees and its Chairman Pro Tempore (which is not acknowledged anywhere in the issue).29

According to a lengthy exposé by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, which dubbed Baguirov “Baku’s Man in America,” he is “known to have close ties to President Aliyev” and was the recipient of funds from the “Azerbaijani laundromat,” which is “a set of intertwined bank accounts used as a slush fund by the country’s elite to buy luxury goods, pay off European politicians, and launder money” in order to “influence American policy in the interest of Azerbaijan.”30

Questionable Origins of an Oxford Centre

There seems little doubt that Azerbaijan, emboldened by its military victory and fueled by petro-dollars, will increasingly seek to purchase the kind of academic semi-credibility that Turkey has for decades sought through the cultivation of scholars willing to present its state narrative as historical fact or at least worthy of consideration as such.31 Even before the war, the 2018 establishment at the University of Oxford of the Nizami Ganjavi Centre through a £10 million donation from a mysterious entity called the British Foundation for the Study of Azerbaijan and the Caucasus (BFSAC), a UK-based foundation with intimate ties to the sister-in-law of Azerbaijan’s dictator Ilham Aliyev, was an indication that Azerbaijan recognized the value of investing in scholarship that reflects favorably on a state hungry for legitimacy.

A 2021 Times Higher Education report on the Ganjavi Centre contained numerous revelations that raised concerns that the Centre may be less than purely academic, among them that “The donation [that established the Centre] was brokered by Nargiz Pashayeva, sister-in-law of President Ilham Aliyev, who since 2003 has ruled Azerbaijan amid accusations of torture, the jailing of political opponents and corruption” and “A member of the family of Azerbaijan’s autocratic ruler [i.e., Nargiz Pashayeva] sits on the board of a University of Oxford research centre that studies the country, raising conflict of interest concerns for academics.”32

The same article quotes Prof. Robert Hoyland, former head of the Ganjavi Centre, as stating that the gift that created the Centre came from “a donor based in Europe” and “was not made to or from BFSAC, but to Oxford University directly, and the deed of gift was made between those two parties.” Hoyland’s assertion flatly contradicts Oxford’s own narrative of the creation and funding of the Ganjavi Centre, and renders the claim of the unnamed Oxford spokesman quoted in Times Higher Education that the university “was made aware of the original source of funds for this gift, which does not come from a government” far from reassuring, particularly in light of the skill with which Azerbaijan’s rulers have hidden the origin of the wealth they have spread around the United Kingdom, as has been extensively documented and reported.33

Indeed, even if Oxford’s own prior statements are correct and the BFSAC was the source of the £10 million gift, given the central role played by Nargiz Pashayeva in the Foundation, the absence of information on where it obtained such a large amount of money, and the comments of Azerbaijan’s ambassador to the UK that the incorporation of the Nizami Ganjavi Centre was one of the “tangible achievements” of his seven-year tenure, there would still be crucial questions that must be answered.34

Rewriting the Past to Dictate the Future

There is a famous, perhaps apocryphal story about French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, who, when asked what future historians will think about the problem of who was responsible for starting World War I, is said to have responded, “This I don’t know. But I know for certain that they will not say Belgium invaded Germany.”

Commenting on this Clemenceau anecdote, Hannah Arendt wrote that “considerably more than the whims of historians would be needed to eliminate from the record the fact that on the night of August 4, 1914, German troops crossed the frontier of Belgium; it would require no less than a power monopoly over the entire civilized world. But such a power monopoly is far from being inconceivable, and it is not difficult to imagine what the fate of factual truth would be if power interests, national or social, had the last say in these matters.”35 Echoing John Adams, she writes: “Facts assert themselves by being stubborn, and their fragility is oddly combined with great resiliency.”

But facts need help to assert themselves. Within Turkey and Azerbaijan, the kind of “power monopoly” Arendt finds “far from being inconceivable” is a reality. Turkey, Azerbaijan and their hirelings continue their well-funded efforts to overwrite the historical record with their “alternative fact” account of the Ottoman extermination of the Armenians, of the history of Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh and of the region generally. Although their efforts are widely rejected in most—but not, alas, all—international academic circles, in the less rigorous realms of journalism and think tanks, their efforts are more profitable. With Armenia in a position of abject vulnerability as a result of the 44-day war and the subsequent Azeri incursion into Armenia proper, it is increasingly clear that powerful forces are lining up not only to dictate Armenia’s future but also its past.

Endnotes:

1 I would like to thank Khatchig Mouradian who offered helpful comments and suggestions on this article and arranged a talk comprising an early version of it at Columbia University in 2018.

2 For the full text of Adams’ argument for the defense, see The Adams Papers, Legal Papers of John Adams, vol. 3, Cases 63 and 64: The Boston Massacre Trials, ed. L. Kinvin Wroth and Hiller B. Zobel (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965), pp. 242–270.

3 Peter Baehr, ed., The Portable Hannah Arendt (New York: Penguin Books, 2000), p. 552. The essay was originally published in The New Yorker, February 25, 1967.

4 See, for example, Michael Vinson Williams, Medgar Evers: Mississippi Martyr (Little Rock: Univ. of Arkansas Press, 2013), p. 237.

5 See Simon Maghakyan and Sarah Pickman, “A Regime Conceals Its Erasure of Indigenous Armenian Culture,” at https://hyperallergic.com/482353/a-regime-conceals-its-erasure-of-indigenous-armenian-culture/.

6 See, for example, the statement by Amnesty International on Feb. 9, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/02/azerbaijan-blockade-of-lachin-corridor-putting-thousands-of-lives-in-peril-must-be-immediately-lifted/.

7 I differentiate Biden’s statement from the oft-cited 1981 Proclamation 4838 of April 22, 1981, “Days of Remembrance of Victims of the Holocaust,” made by Pres. Ronald Reagan, which stated that “the genocide of the Armenians before it, and the genocide of the Cambodians which followed it—and like too many other such persecutions of too many other peoples—the lessons of the Holocaust must never be forgotten.”

8 The texts of all relevant resolutions and statements may be found at https://www.armenian-genocide.org/affirmation.html.

9 On Turkey’s role in the 2020 war, see for example Haldun Yalçınkaya, “Turkey’s Overlooked Role in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War,” arguing that “Turkey’s most significant contribution to Azerbaijan’s victory in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War was neither the drones it supplied nor the military advisors it allegedly provided, but three decades of meticulous army building” (https://www.gmfus.org/news/turkeys-overlooked-role-second-nagorno-karabakh-war). However, see also Ece Toksabay, “Turkish arms sales to Azerbaijan surged before Nagorno-Karabakh fighting” (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-armenia-azerbaijan-turkey-arms/turkish-arms-sales-to-azerbaijan-surged-before-nagorno-karabakh-fighting-idUSKBN26Z237. The fact is that Azerbaijan’s military victory was made possible by both Turkish military hardware and expertise.

10 Bedross Der Matossian, “Ambivalence to Things Armenian in Middle Eastern Studies and the War on Artsakh in 2020,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 54.3 (August 2022), p. 534.

11 For Ülgen, see https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/07/26/redefining-u.s.-turkey-relationship-pub-85016; for Gutbrod and Wood, see https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/14/armenia-turkey-genocide-ottoman-empire-history-rapprochement-diplomacy-public-opinion/; for Abdul-Ahad, see https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n12/ghaith-abdul-ahad/each-rock-has-two-names.

12 Jennifer Dixon, Dark Pasts: Changing the State’s Story in Turkey and Japan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), p. 11.

13 See “An Open Letter Concerning Historians Who Deny the Armenian Genocide: October 1, 2006,” https://genocidescholars.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Scholars-Denying-Armenian-Genocide-.pdf.

15 Incredibly, the court found that such a statement “did not amount to advocacy of hatred or intolerance.” See https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/cases/ecthr-perincek-v-switzerland-no-2751008-2013/.

16 https://twitter.com/sinanulgen1/status/1386378244048441344?lang=en.

17 See https://edam.org.tr/en/executive-and-supervisory-board/. According to the website, “EDAM does not take institutional positions on public policy issues, therefore the views published herein, in order to promote debate on topics of interest to EDAM, are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of EDAM.” Yet the statement on Biden’s declaration was made by EDAM as an institution. Perhaps denial of the Armenian Genocide is not a “public policy issue”?

19 See “Carnegie Europe and Thomas de Waal under critique,” at http://www.agos.com.tr/en/article/25781/carnegie-europe-and-thomas-de-waal-under-critique and https://drive.google.com/file/d/1r0B2KxaQINdG-qO-1IsdJChFEovHxSsj/view.

20 “We are here today to… celebrate this glorious victory.” See “In Azerbaijan, Erdogan calls for new Armenian leadership,” https://www.dw.com/en/erdogan-praises-azerbaijans-glorious-victory-calls-for-regime-change-in-armenia/a-55898699.

21 The absurdity of emphasizing the “reconciliation process” calls to my mind Bob Dylan’s response when asked if “it’s pointless to dedicate yourself to the cause of peace and racial equality.” He replied: “Not pointless to dedicate yourself to peace and racial equality, but rather, it’s pointless to dedicate yourself to the cause; that’s really pointless. … To say ‘cause of peace’ is just like saying ‘hunk of butter.’ I mean, how can you listen to anybody who wants you to believe he’s dedicated to the hunk and not to the butter?” Quoted in Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews (New York: Wenner Books, 2006), p. 105.

22 On these Azerbaijani efforts see, inter alia, George Bournoutian, “Rewriting History: Recent Azeri Alterations of Primary Sources Dealing with Karabakh,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 6 (1992-1993), pp. 185-90; “The Politics of Demography: Misuse of Sources on the Armenian Population of Mountainous Karabakh,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 9 (1996-1997), pp. 99-103.

23 See, for example, “’One nation, two states’ on display as Erdogan visits Azerbaijan for Karabakh victory parade.” https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20201210-one-nation-two-states-on-display-as-erdogan-visits-azerbaijan-for-karabakh-victory-parade.

24 https://www.gmfus.org/news/turkeys-overlooked-role-second-nagorno-karabakh-war.

26 https://coe.mfa.gov.az/en/news/3509/shusha-declaration-on-allied-relations-between-the-republic-of-azerbaijan-and-the-republic-of-turkey. The declaration states, inter alia, “Emphasizing that the wise sayings of the founder of the Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, and the national leader of the Azerbaijani people, Heydar Aliyev, ‘The joy of Azerbaijan is our joy and its sorrow is ours too’ and ‘One nation, two states’, are regarded as the national and spiritual heritage of our peoples.”

27 See Marc A. Mamigonian, “Academic Denial of the Armenian Genocide,” Genocide Studies International 9.1 (Spring 2015), pp. 61–82. For important additional discussion see Richard G. Hovannisian, “Denial of the Armenian Genocide 100 Years Later: The New Practitioners and Their Trade,” in Genocide Studies International 9.2 (Fall 2015), pp. 228–247; Keith D. Watenpaugh, “A Response to Michael Gunter’s Review of The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey: A Disputed Genocide,” in IJMES 39.3; Israel Charny, “Review of Michael M. Gunter, Armenian History and the Question of Genocide,” in International Journal of Armenian Genocide Studies 1.1, pp. 88-93.

28 Saleha S. Mahmood, “A Word About Ourselves,” JMMA 32.2 (June 2012), no page number. It is also worth noting that, since around 2006, articles that skew to Turkey’s denialist narrative and book reviews praising works that deny or cast doubt upon the Armenian Genocide began appearing regularly in the pages of JMMA, later to be joined by writings uncritically supportive of Azerbaijan. This trend at JMMA roughly corresponds with the commencement of the modern era of academic denial of the Armenian Genocide that was inaugurated with the appearance of Guenter Lewy’s The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey: A Disputed Genocide (University of Utah Press, 2005), which was published through the efforts of M. Hakan Yavuz, the journal’s book review editor. In a marvelous example of vertical integration, Yavuz, the individual who arranged for the publication of Lewy’s book in the first place, is the same individual in a position to have it reviewed favorably in JMMA by Yücel Güçlü, a career foreign service employee of the Turkish Foreign Ministry whose own genocide denying book Armenians and the Allies in Cilicia, 1914–1923, would, in turn, be published by the University of Utah Press in 2012. All in all, since 2006 not a single work presenting the Armenian Genocide as a historical fact has been reviewed favorably, and not a single work attempting to deny the “genocide allegations” has been reviewed unfavorably. One wonders if any other issue has received as consistent treatment by this journal which professes to provide “a forum for frank but responsible discussion of issues relating to the life of Muslims in non-Muslim societies.”

29 In a happy coincidence, Baguirov is married to the daughter of ex-Turkish ambassador to the US, architect of modern Turkish denial in the US, and advisor to Hakan Yavuz’s Utah Turkish Studies Project, Šukru Elekdağ.

30 Jonny Wrate, “Baku’s Man in America,” online at https://www.occrp.org/en/azerbaijanilaundromat/bakus-man-in-america.

31 This is not to suggest that such efforts have not been made before now. Most notorious, perhaps, was Harvard’s Caspian Studies Program, funded “through a $1 million grant from the US Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce and a consortium of oil and gas companies led by Exxon, Mobil, and Chevron, all of which had commercial interests in the region,” and headed by Brenda Shaffer. For detailed exposés see https://www.occrp.org/en/corruptistan/azerbaijan/2015/06/22/profile-of-an-undercover-lobbyist-for-azerbaijan.en.html and https://www.rferl.org/a/azerbaijan-lobbying-western-media-brenda-shaffer/26592287.html.

32 On the Ganjavi Centre, see https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/concern-over-azerbaijan-ruling-family-influence-oxford-centre.

33 See, for example, https://www.transparency.org.uk/azerbaijan-laundromat-NCA-latest-news-Westminster-Magistrates-Court.

34 As far as we can determine, the BFSAC has ceased to exist; see https://register-of-charities.charitycommission.gov.uk/charity-search/-/charity-details/5080778/governance. The comments of Azerbaijani Ambassador to the United Kingdom Tahir Taghizadeh can be found at https://aze.media/diplomat-on-the-line-ambassador-tahir-taghizadehs-seven-years-in-london/.

35 The Portable Hannah Arendt, pp. 554, 570.

Be the first to comment