My name is Nareg Hovsep Seferian.

It ends in “-ian” – characteristic for most Armenian surnames, also with its other spelling, “-yan.”

“Seferian.” That means “traveler.” My ancestors were probably merchants. Little surprise there for any Armenian. The sefer part is ultimately an Arabic root, but it surely became a surname for Armenians under Turkish or Persian rule. “Safarian” is another version. So, alongside the Armenian suffix, that surname reflects the mark of medieval and modern empires and neighboring cultures.

“Hovsep,” my middle name, is Armenian for “Joseph” – a name from the Bible, Hebrew via Greek. This is an indication of how Armenians have long formed part of the broader cultural landscape around the Mediterranean and Middle East. It also indicates the Christian heritage which forms a significant part of the Armenian identity. It is my father’s name. And my nephew’s name – the first-born grandson of my immediate family. That tells you something about naming practices prevalent in Armenian culture.

“Joe,” by the way, is my restaurant or coffee shop name. It can be convenient to have one of those.

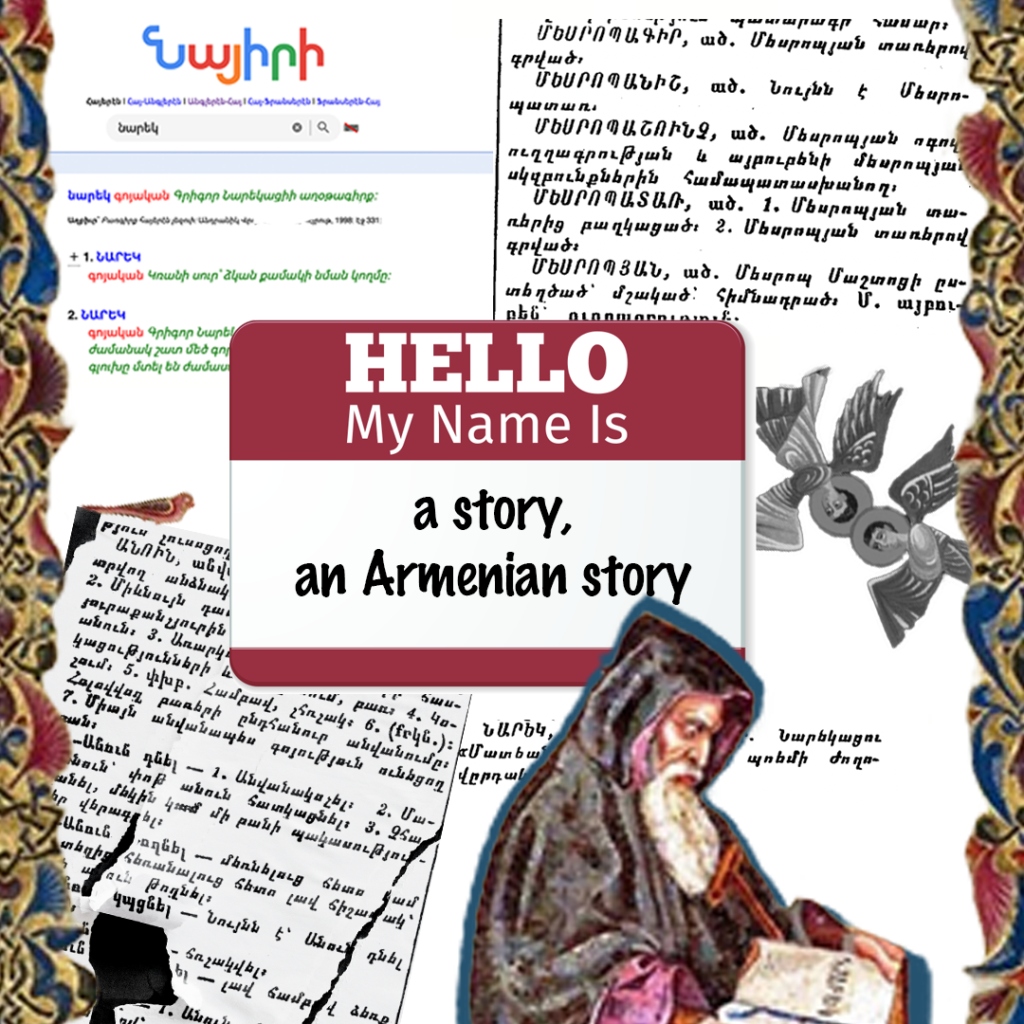

“Nareg.” Now there’s a rich story, set a thousand years ago, featuring a monk at a monastery near Lake Van. He is known as Grigor-Krikor Narekatsi–Naregatsi, depending on your preferred Eastern Armenian or Western Armenian pronunciation. Among many works, St. Gregory of Nareg is most celebrated for writing The Book of Lamentations, a series of mystical prayers. It is considered the holiest text after the Bible in the Armenian tradition. The Nareg, as it is more commonly called, is invoked to cure illnesses.

My full name tells a story. It tells an Armenian story – a multi-cultural and multi-geographical story, with both religious and mundane elements, a story highlighting both Homeland and Diaspora.

I grew up in India, where I was most probably the only Nareg out of literally a billion people. When I went to college in Yerevan, there were four other people in my class with my name. At first, I felt like I had been deprived of something special. But very soon, it occurred to me how wonderful it was to find myself in a place where that name is known and cherished, where St. Gregory and The Book of Lamentations is venerated, where I didn’t have to repeat my name or spell out N-A-R-E-G when introducing myself. Where I do not need to have a restaurant or coffee shop name.

According to Hrachya Ajarian’s Dictionary of Armenian Personal Names (Հ. Աճառյան. «Հայոց Անձնանունների Բառարան», ԵՊՀ, 1942), “Nareg” appeared as a masculine given name only in the early 20th century. Think about your own name, how you relate to it and how it forms part of the cultural landscape where you are. Maybe your surname does not end in “-ian” or “-yan.” It could end in “-uni,” “-oglu,” “-ov,” “-nts,” or nothing in particular. What does your surname mean? Do you know how your family received it? What about your name? Why was it chosen?

To find out about your own name, you can access Ajarian’s dictionary and a whole lot more on Nayiri, perhaps the richest resource of the Armenian language online. You could also ask your parents and the elders in your family.

(Here’s another layer to it: how are your name and surname spelled? Armenian families have passed through so many Middle Eastern and European languages that a diversity of transliterating Armenian have come up in the Latin alphabet. For example, “Meguerditchian,” “Mkrtchyan,” “Migirdicyan,” and “Mkrtschjan” are all the same surname.)

Many Armenians have multi-faceted names, middle names and surnames. Maybe your name is common in English, Russian, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Maybe it is something from those cultures with a private Armenian equivalent. Perhaps you have a public name only in Turkish. Part of the legacy we bear causes us discomfort or pain. All of it makes us who we are.

Tarkmanchats – the Feast of the Holy Translators – is celebrated in early-to-mid-October every year. In 2022, it is on Saturday, October 8. More than one person has told me that the Armenians are the only people who set aside a special day to commemorate translators – Mesrop Mashtots and his students above all, who, by tradition, produced the Bible in Armenian in the early fifth century AD. We emphasize how that translation was a seminal event in the crystallization of the Armenian cultural identity and, certainly, the language. Mashtots is credited with creating the Armenian alphabet, after all. It was in his time that Classical Armenian was codified or standardized as a literary language. There is a strong Armenian tradition of translation that goes far beyond holy scripture. As a global nation, many Armenians experience multilingualism and translation in their day-to-day lives. We also tend to trans–late quite directly, “carry-across” meaning and culture from continent to continent.

Tarkmanchats is also the day the Armenian church remembers St. Gregory of Nareg. That makes it my name day. In the past, many babies were named for saints and other figures commemorated in liturgical calendars on or near the days of their birth. A name day and a birthday were often conflated. The traditional greeting to someone on their name day is, «անունովդ ապրիս», anounovt abris, “May you live with your name” – i.e., may you have a long life, true to your name.

Nowadays we have many interesting and rich names which may not feature on church calendars, so many of us cannot claim a name day of our own. I say let’s go with Tarkmanchats for all of us. I doubt Mesrop Mashtots would mind, and I expect all the Mesrops out there would be glad to share the celebration. I know I would, as a Nareg myself.

So on Saturday, October 8, discover and celebrate your name, and – if you feel inspired – post something with the hashtag #ArmenianNameDay. You could add #ՀայԱնուն too. (That’s HayAnoun – Armenian Name.)

At this moment, when the Armenian nation is facing serious challenges, it may seem trite or even insulting to go about posting something with a hashtag. I hope, however, that Tarkmanchats this year – and every year – can serve as a reminder of a significant part of our identity, that no matter how distressing the situation in Armenia or Artsakh, we not only carry, but celebrate our Armenian heritage. Something so fundamental to how we think about ourselves attests to the pathways of our culture. It reflects the resilience of the Armenian identity.

My name is Nareg Hovsep Seferian. What’s yours?

Peter Antonian, my father immigrated from Armenia in 1906, he was 16 and was married and had two children that were to come later, he thought them dead after the war, and they didn’t reappear until 1956 in Marseille, France. For years, he went by the name Moses Antoian being afraid that when he arrived they would not let him off the ship.Our cousins got him to change it back to Antonian from Antoian, as a kid I received a new lesson about the (old country) every night. Also, I learned the more important stories from my uncle George Kallagian, the owner of Near East Pilaf, the stories he told are so horrible some about when they were led out of the country to Syria.

Parev Nareg,

My name is Perouz Seferian. I was named after my grandmother who was stoned to death on the caravan trail. When Armen Aroyan took me on pilgrimage along the caravan route, he asked me if I wanted to start at my village of Kalan and follow the caravan route to where it ended in Diyarbakir. I asked to start in Diyarbakir and follow the route back to their home in Kalan. It was my personal act of defiance and resistance. I wanted the Turks and Kurds to know that Perouz was still here, that she knew what they had done, and that it would never be forgotten.

Following is an excerpt from my father’s writing about the murder of his grandmother.

“My grandmother became very tired and was unable to walk any longer. My mother and Ankin, the wife of my father’s brother, Setrag, walked with her for some distance, holding her by her arms, but my old grandmother fell, completely exhausted. My mother and Ankin lifted her, carrying her in turn. My grandmother was on my mother’s back when gendarmes came from behind. One of them furiously pounded my mother’s head with the butt of his gun. She fell down with my grandmother still on her back. Screaming, covered in blood, my mother got up and escaped. The gendarme ordered my grandmother to also get up. She was not able to move. Furious, he picked up a large rock and smashed it into her face. A second gendarme helped him slaughter my grandmother by repeatedly hammering her head with the butt of his gun.

Forced forward with the lashing of whips, we all followed the caravan with shattered hearts, ceaselessly lamenting the death of our beloved grandmother. Her body was left uncovered, unmarked, on that cruel mountain road between Dogyrmai and Asagikoy.”

I enjoyed reading your article. I have a question; how come many Armenian surnames in Russia and the former USSR ended in -iants/-yants instead of -ian or -yan?

I have searched the web and the only explanation I have found is that the -iants or -yants ending of Armenian surnames serves as a possessive suffix. If true then why is is used mostly in Russia?

I am taking the liberty of an input here. You raise a good question. It can be interpreted in various ways. From what I surmise, the “iants/iantz” or “yants/yantz” derive from a dialect of our language that was spoken/used in certain regions of Armenia, from Armenia of the centuries past to right before the 20th century. I remember my Kharpertzi medzmama’s dialect included words that were of local roots only spoken in her region. Some incorporated in the mainstream language, coming from writers, authors of the area, and thus acknowledged and used with the next generation. “Iants/iantz” or “yants/yantz” denotes to one’s family belonging. As in “Ian” “yan” but enhanced, for lack of better words, with the “”ts” “tz” those being the intonations derived from the melding of local languages, in this case Russia or the eastern countries. In my husband’s last name as his is Mergeanian, observe how the simple mid part of the name “jan” is spelled “gean”, a result of the Romanian language influence. Hope this was helpful.

Your article was a wonderful tribute to the Armenian culture. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for your inspiring article. We need to continue to thrive even in the worst of moments of our history, keeping in high spirits of our sourp heritage and faith.

My Armenian literature teacher in highschool back in the 70s Beirut was Mr Nazaret Seferian, we students called him Baron Seferian. Quite an astute scholar, he taught us the value of our language. We sure were lucky to have had him as our teacher.