This book began when my mother insisted that I meet my cousin Nancy. I’m not sure what the cousin relationship is, as Nancy is married to my step-first-cousin, Robert Vinetz; but for my mother, family was family and there were no rankings or levels. Nancy, my mother said with particular firmness, had been to Turkey, and she wanted to talk about her trip. Everyone knew that Turkey was the center of my world. I finally met her at a party my parents hosted to celebrate my PhD in Islamic Art and Architecture with an emphasis on Turkey and its Ottoman past.

This book began when my mother insisted that I meet my cousin Nancy. I’m not sure what the cousin relationship is, as Nancy is married to my step-first-cousin, Robert Vinetz; but for my mother, family was family and there were no rankings or levels. Nancy, my mother said with particular firmness, had been to Turkey, and she wanted to talk about her trip. Everyone knew that Turkey was the center of my world. I finally met her at a party my parents hosted to celebrate my PhD in Islamic Art and Architecture with an emphasis on Turkey and its Ottoman past.

But my new cousin Nancy Kezlarian had been to a Turkey I did not know. She had traveled there among a small group of other Armenians and had visited her father’s birthplace of Sivas, her paternal grandfather’s hometown of Tokat and her maternal grandfather’s village of Tadem. In Husenig, she even found her maternal grandmother’s house, and she had brought back stones from all four ancestral places. Meeting Nancy seemed like a cosmic moment. My PhD dissertation, and then book, relates the importance of Ottoman houses as images in Turkish memory as the Ottoman Empire waned and the Turkish Republic emerged. In other words, it was about how memory gets stuck to houses. But I had not considered that the period I was covering was also the period of the Armenian Genocide, which was the reason that Nancy’s family had lost their houses and their connection to their beloved homeland. It was why her trip had been a pilgrimage, not a vacation.

Only during my research in Anatolia in the mid-1990s had I come to realize that there was an ominous black hole in my received knowledge and thus in my own work. But I didn’t know how to go about a repair until Nancy appeared with her stories about Armenians who were searching for their houses. Nancy [Nancy Kay in my book] is the one who introduced me to Armen Aroyan. Armen, as my book documents, made Nancy’s and thousands of others’ “homecomings” possible. He welcomed me on his buses, which then gave the pilgrims permission to welcome me, a non-Armenian (and a “Turkish scholar” to boot) on their very personal trips.

I made my first pilgrimage in 2007 with no knowledge of what was ahead of me or even what I was chronicling. I only knew that the pilgrims with whom I would travel were searching for their ancestral towns and villages, the ones lost to their own parents and grandparents. Almost all held a secret hope: that they might even find the ancestral house. Over the course of eight years, I joined Armen with 12 different pilgrimage groups, crisscrossing historical Armenia in caravans of mini-buses that were bursting with emotions: yearning, mourning, excitement, pride, love, loss and rage. By 2015, I had accompanied over 100 pilgrims, each of whom had created their own precious, individual moments. I also had amassed scores of accounts from other pilgrims, including many who had not traveled with Armen. These accounts were gathered from memoirs and books, some from as early as the 1950s, but also from blog posts, films and even interviews from serendipitous meetings. A good chunk of enriching information came from the trip-memoirs that Armen’s pilgrims had written for a book he was compiling called The Pilgrim Speaks, and a selection of videos he had made of these journeys, now housed at the University of Southern California’s Dornsife Institute of Armenian Studies. My linchpin, however, was the series of conversations with pilgrims that went on long after their journeys, many having become treasured friends.

By my final trip in 2015, I had amassed an enormous archive of feelings. The year before my final trip, I was invited to be a research fellow at the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas at Austin (UT). There, in a little windowless office, I could go through all my notes, put them into my computer so they would be organized and searchable, and try to make sense of earlier trips from what I knew of later ones. My first trip, the only one taken on a large tour bus, was filled with members and families of the western region of the Armenian Relief Society (ARS), all high-spirited yet deeply serious, and, to my confusion, speaking Armenian among themselves. In a generous rotation, one from the group would sit next to me to fill me in on what was happening; for example, why the bottle of Arak/Raki had come out, and why people were suddenly singing and dancing in the aisle. The bus had entered Cilicia. By 2015, I was familiar with a large number of these “locale” songs, had learned their history, and could put that part of these trips into a category. But the magic of that moment could only come from being there—revived in my notes that had recorded it.

In Austin, I could also transcribe the videos that Armen had lent to me, plus the ones I had taken myself. Most were in English, some in Armenian, often with Turkish or Kurdish in the background. Magically, two brilliant young UT graduate students appeared after hearing one of my talks and offered to be my assistants. Lisa Gulesserian translated videos and even books from Armenian and helped contextualize them, while Mine Tafolar translated the Turkish from videos in all sorts of dialects that went beyond my grasp, including the many songs sung to the pilgrims by local children. A fortuitous email connection with a Kurdish graduate student in Turkey solved the problem of translating Kurdish. As I began to review what had happened, what was said, what was sung and what was danced, I found that I was juggling over 400 pilgrims, each of whom, it seemed, imagined their ancestral house as their homeland’s beating heart.

I surprised myself when I couldn’t help but identify the categories of experiences that I had watched as spiritual ones. This did not seem like an appropriate direction for a scholar, even one who is concerned with memory and feelings. But when pilgrims found their houses or the places where they had once been, they responded as if they were standing on holy ground. For one, signs and symbols of something consummate floated everywhere. In Yozgat, Mary Ann arrived from Massachusetts to find that her ancestral house had been made into an ethnographic museum, furnished as if it had been left in the early 1900s. However, it had no reference to her family or even that it had been an Armenian house, although it was in a historically Armenian neighborhood. But when she saw an organ among its furnishings, she knew this truly was her house.

“There, in one of the upstairs salons, was a turn of the century organ with a Mason and Hamlin Boston label, which I felt was truly a sign to me, as a church organist, that this was my family home and also that it was welcoming me back.” Later, she added, “Imagine, an organ, and from Boston!”

Yet, for Mary Ann it was also a tense moment, as her house had become a marker of a homogenized “Turkish history,” signaled by the Turkish flag that stood in front of it. If history had not been what it was, she might have shown her Yozgat family photographs to the receptionist or to the armed guards at the door. Mary Ann’s husband Ed, however, looking at the two Turkish-speaking guards, had no desire to replace past appropriations with new commonalities. Instead, with his ever-present wit, he said to them, in clear English, “This is my wife’s house, and you are fired!” (But he said he wouldn’t have done it if he hadn’t felt confident that they would not understand.) But Mary Ann’s focus was on the sign that she was home. The house’s welcome could not heal what had happened to her family and why she never knew her own grandmother, but a spiritual connection had filled the void between her present self and her ancestral past.

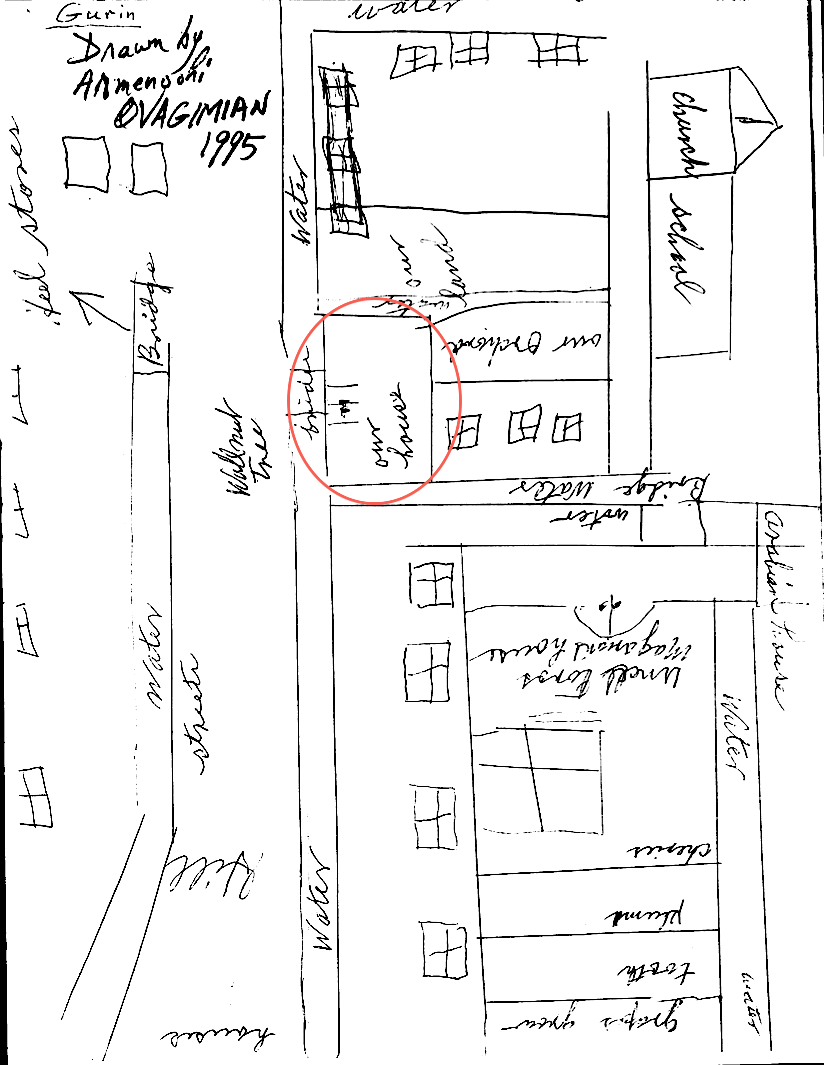

Priscilla hunted for her family house in Husenig. Although a house-by-house and street-by-street map had been recreated of pre-genocide Husenig, there was still some ambiguity. That is, until a sign materialized.

“One boy held out a baby chick to me, asking if I wanted it. To you, this might mean nothing, but to me it was like a miracle. I must tell you that nowhere else on this trip did I see any chickens. I must also tell you that when I was a child, my father would give my sister and me and our cousins baby chicks or baby ducklings for Easter. I immediately had the feeling that he was right there with me.”

Signs and symbols seemed to emerge from nowhere. But pilgrims also instigated special kinds of engagements, which I identify as a series of rituals that they seem compelled to perform. Some were invocations; the pilgrims stood on their own “home ground” and spoke aloud to their ancestors (almost always ones they had known). Some made shrines or left votives (hiding photographs in places that stood for their lost house). Some rituals involved the digging and carrying of earth or stones, which released the spirits of the land. Each, in the moment of performance, actively re-situated the pilgrim in their homeland’s living history. Anoosh, for example, could now say that he had spoken to his father in Keghi.

As early as 2014, I described my project to Kate Wahl at Stanford University Press, who is deeply supportive of Ottoman-Armenian related work. She was excited about what was unfolding. But by the time it was ready for press, the approach that investigated rituals, signs and symbols had grown to include how pilgrims used the things they carried with them, like old passports, hand drawn maps, photographs and especially stories and music, as intermediaries between the people they loved and their homeland, lost to a brutal exile.

Moreover, when they encountered Islamized Armenians, sometimes relatives, in a place they thought had been emptied of Armenians altogether, their homeland took on new life yet again.

Watching what seemed like the actualizing of a true pilgrim’s quest, I also came to interpret these pilgrimages as poetry and the pilgrims as poets. What became clear to me and what I present in my book is how what each pilgrim did on reaching the heart of their homeland, conveyed, like a successful poem, the experience of being moved.

Utterly fascinating. Vestiges of a lost world. Highly spiritual bordering on ghostly.

Dear “Armenian Realist”:

With all due respect, I don’t see how you’re being a “Realist.”

Perhaps you are implying that ‘Western Armenia is gone forever so let’s just reminisce around the dining room table with some Turks and eat shish kebab.’

President Erdogan has been expressing genocidal aims against Armenians and Armenia:

(1) “Remnants of the Sword.”

(2) Praising the genocidal invasion of the Caucasus and Armenia by Enver and the “Army of Islam” in and after WW 1 by Ottoman forces and later Kemal Ataturk.

Maybe that is something we should be a “realist” about?

I wonder what the author, Dr. Bertram, thinks about the 2020 war against Armenians by Turkey and Azerbaijan, with the help of Israel.

Thank you Professor Bertram for undertaking this research and publishing this book.

I participated in the Zoom conference organised for your book by the Promise Armenian Institute at UCLA and I was particularly touched when you explained that you, as a person of Jewish ancestry were not interested in undertaking a similar “pilgrimage” yourself for your own family’s ancestral village (s), but that you were personally touched by the emotions you witnessed during these Armenian pilgrimages.

Nations are made of individuals with different feelings at different times in their lives. I believe that we should cultivate moments of friendships between people rather than moments of strife. I therefore renew my invitation to come and visit the medieval Jewish cemetery in the valley behind our mountain in Yeghegnadzor (Yeghegis).

As a small detail, may I also suggest that the musical instrument (made in Boston) shown in a photo in this article is more accurately called an “Harmonium”, not an “organ”. A harmonium is a foot-operated wind/keyboard instrument, of the same family as “organs”, but it is a stand-alone instrument without those huge pipes typical of organs.

These trips are not “pilgrimages” but one of very few available avenues by which the dispossessed can reconnect with their indigenous patrimony. I resent any notion that simply visiting the lands of our ancestors heals trauma and provides definitive closure in and of itself. We belong on our ancestral homeland and one day that will be permanent.

“We belong on out ancestral homeland.” How does that apply to people that a mixed race? I am 50% Western Armenian… although I’d love to Turkey for research, I don’t want to live there. I’d rather connect with my 5% Swedish heritage. I’m Atheist – I would not survive. Both sides have different versions of god, and I don’t accept either version of god.

To catch the poetry of a home place, and the experience of what it was like to be in a home place of one’s family, is a wonderful gift.