On February 19, 2020, I received an email from writer and scholar David Calonne, whose review of my 2017 novel The Naked & the Nude was published in the Armenian Weekly last summer. Calonne was invited to guest lecture about William Saroyan at the University of Chicago. He asked if I could share any influence of Saroyan on my writing. The following brief memoir is my response to his request and is being published in the Weekly in honor of the famed writer’s 112th birth anniversary.

I started writing stories when I turned 14, and it was in that same year that I read in an anthology of short fiction what was really a kind of prose poem by William Saroyan called The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze, which was like a piece of music that moved me so deeply I wanted to sing like it for the rest of my life.

I was born in 1940, and by 1954 Saroyan’s little poesy was already 20 years old and had moved many other writers, including as you may know Jack Kerouac, who was born in 1922 and must have also been about 14 when he read it with the same kind of thrill.

But it would take a while for me to read more of his work, since the work of Hemingway was having an even greater effect on me, and yet sensitive to the music of writing I was already aware of how their voices were related.

Then turning 19 I had to leave college, and I moved to Greenwich Village where I found in the local library near my room a copy of The Saroyan Special that was a selection of almost 100 of his short works that he had written in his twenties, and they all had that special music that was related not only to Hemingway’s but in all the other writers I loved.

Some of the selections were as special as The Daring Young Man, and while others were repetitive and excessive they were all readable, and he would remain one of my heroes until here now in this humble tribute when I just finished re-reading one of his masterpieces, The Human Comedy, that he wrote around the time my father was crippled by a stroke after I had just turned three.

My father’s stroke was one of the most important events in my psychodrama that would lead to my first book, which was published in 1971, and my publisher Pantheon mailed the galley proofs to Saroyan for a blurb, and though his reply arrived too late, Pantheon mailed it to me.

It was handwritten on a little sheet of note paper from a notepad, and I was deeply upset when I lost it. I was very troubled at the time due to the end of a painful relationship, and living in emotional turmoil I had let friends of friends crash in my pad; so when I found the note was gone I suspected someone had stolen it, which caused me a terrible grief since I treasured that little note as if it were from a father, and unable now to remember it verbatim it blurs in my memory like the memory of my father before the stroke.

It said he got the galleys as he was boarding his plane from New York to Paris where he was living at the time, and he read them on the plane, but I never learned anything more and I lost touch with Pantheon soon after.

Yet I remember it said something about my book being written with the passion of youth that grabbed the reader immediately, and I do remember verbatim the last line that touched me very deeply: It lingers in the mind.

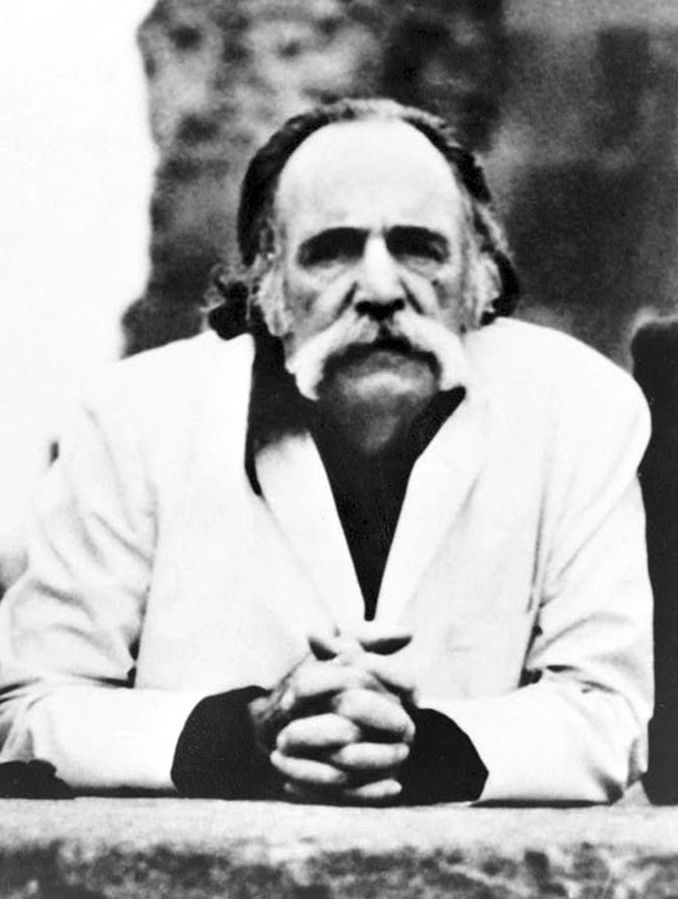

And this line would forever linger in my mind until now remembering the only time I would meet him in person when he was living in Fresno a year or so before he died, which was in 1981.

I don’t know why he moved from Paris to Fresno, but I went to visit him as soon as I found his address. My mother had moved there by then, and I would drive from Berkeley to visit her on the weekends. It was on one of those weekends I drove from where she lived near Herndon and Cedar Streets to the other side of town where he had bought a little home like hers, and he was gruff when he opened the door as if I might be a door to door salesman or whatever, until I told him my name and that I had come to thank him for what he wrote about my book years earlier.

Oh yes, he said in his strong voice that I had never heard before, though it was exactly like how I had imagined it from his plays that I had seen over the years; and his personality was the same as in his narrators and personas, which was the opposite of mine and was actually a lot like my mother’s with the same kind of warmth and openness, and when he saw I was shy he immediately went into a monologue that was non-stop.

The hallway and the rooms were stuffed with books and stacks of newspapers and magazines and who knew what else while a record was playing on a little phonograph and a television was on with the sound off while he was writing, as if he needed constant stimulation like in a Paris apartment in a busy street, and the walls too were covered with pictures as if a blank space was an enemy that had to be filled, and among them were little paintings that were painted in watercolor as if by a child.

Were they by his grandchild, I asked timidly, and instead of feeling insulted he merely said no, he painted them himself, and he returned to his monologue as if he were spontaneously composing one of his plays or stories from a bric-a-brac of memories, until seeing I was going to stay reticent he didn’t have anything more to say, and I left feeling so sad and angry with myself and my damn shyness.

He had been my father figure since I was a boy, and there was so much I wanted to ask him like I wanted to ask my father who couldn’t talk to me, and he had no clue as to how deep he was in my psyche as if I were just another fan, and he died a year or so later.

———-

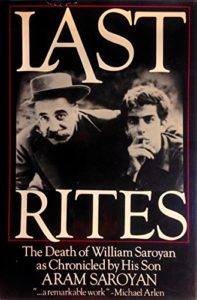

Later that same month, I decided to email Aram Saroyan, commending him on the 1984 publication of Last Rites—a profound essay written through his tortured lens about the last few weeks of his father’s life.

Dear Aram,

I just finished reading your book about your father, Last Rites, and it is the most moving book about a father and son that I have ever read, and it makes me feel embarrassed that I was so naïve in writing my little memoir about him a couple of weeks ago when I was so ignorant of how abusive and selfish he could be with you and your sister, particularly your sister whose own death was so sad, which reminds me not only of the dark side of other writers but so many of us who were wounded in childhood and never fully recovered, of Tolstoi and his illegitimate children and Hemingway and his transsexual son to whom he never spoke again in the last 10 years of his life and Frost whose son killed himself. “Beware of this, O ambitious youth,” wrote Melville, “all mortal greatness is but disease.”

On one hand I regret not knowing of your book these past 40 years since it was published, and on the other I think I was not ready for it until the years would pass to our old age before I would finally meet you and email you my little memoir and ask if you had written about your father and then find your book in the Berkeley Library, and I am now hoping I can find on line the one about your mother. Your childhood family had such a sad story, and yet I love sad stories when they end like yours with heartbreak and tears that make us see what the Buddha meant by what he called Old Age, Sickness, and Death, in his First Noble Truth.

Aram’s reply to Pete

Peter, Thanks so much for your generous response to Last Rites—I’m gratified and touched. At the same time, I urge you not to mar your own touching cameo about Bill and you before you read my memoir. In my opinion it’s irrelevant to the piece which should and does stand as a valid portrait of the two of you, a moment all its own which the reader will and should appreciate for itself. Warmly, Aram

A lovely piece. Najarian’s books do have a way of lingering in the mind, as Saroyan said. They deserve a wider audience.