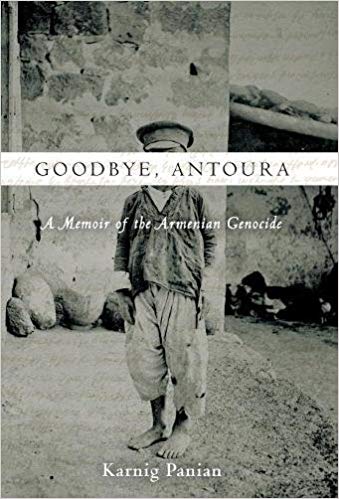

GOODBYE, ANTOURA

GOODBYE, ANTOURA

A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide

By Karnig Panian

191 pp. Stanford University Press

$22.50

The book Goodbye, Antoura is a memoir by Armenian Genocide survivor Karnig Panian. In the memoir, Panian reviews his life, revealing painful experiences and tyranny as an orphan in Antoura, Lebanon. The orphanage was a Christian monastery that the Turkish authorities occupied to convert Armenian children and teenagers to the Islamic religion and culture. The author describes in vivid detail the horrific circumstances his friends and classmates endured while many perished under harsh rules, punishment and lack of food. While he experienced several episodes of darkness and sadness in his life, he depicts the inhumanity of genocide with the dilemmas he and other young children faced under captivity. The children were controlled by a regime that was determined to wipe out the presence of Armenians in their historic land. The Ottomans gained the most in their economy from the Armenian population. The Armenians’ labor and skills were unmatched. They engaged in every aspect of the empire under the Turkish rulers over a span of decades; however, when the Young Turks usurped total rule, they began the deterioration of their relationship with the Armenians who were always the most loyal citizens.

The book was originally published in Armenian in 1992; however, Panian’s daughters’ Chaghik (nee Panian) Apelian and Houry (nee Panian) Boyamian wanted to have their father’s memoir read by a new generation of Armenians and non-Armenians. Panian’s story inspires humanity through his portrayal of a child’s perseverance, courage, stamina, faith and will to survive at all odds. He represents other children who survived and perished collectively under similar ordeals, and how they worked to avoid atrocities, banishment, suffering and death. The children and adults who survived were deprived of their youth, family, well-being and a normal life in a civilized society. The youth were forced into adulthood by the enforcement of military decree and usurpation by the Young Turk regime.

Readers can feel the gravity of the pain of losing a loved one, and especially the depth of a child who is experiencing death all around him in a genocide. Not only has he witnessed the demise of his immediate family, but also of his contemporaries. The victim wonders if the society has gone mad and what his descendants did to deserve their fate.

Karnig Panian passed in 1989. He was a teacher and devoted himself to the Armenian community of Lebanon. The memoir was published by the Hamazkayin Armenian Educational and Cultural Society of Beirut, Lebanon, and by the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia in Antelias, Lebanon as “Memories of Childhood and Orphanhood.” The Stanford University Press edition includes Chapter 9 of the unpublished manuscript. The principal contributors to the new publication are noteworthy in their respective specialties. The Panian family is indebted to several advisors and scholars for their fervent support of the new publication. They are mentioned in the book.

The Foreword was written by distinguished scholar Dr. Vartan Gregorian, president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York. His long career in academia illustrates a commitment to education. The unique features of the English edition are credited to translator Simon Beugekian and editor Aram Goudsouzian. The Introduction and Afterword were both written by Professor Keith David Watenpaugh, whose academic career reflects his longtime commitment to human rights and genocide studies. Others in these fields, like Professor Richard G. Hovannisian, rallied for the fruition of the new publication as well. Notably, Kate Wahl, the Editor-in-Chief of Stanford University Press, California encouraged, guided and supported the publication procedure.

Dr. Gregorian’s Foreword gives the reader insight into the human tragedy of genocide. He analyzes the chilling examples of dehumanization etched in young Panian’s mind as a child. Gregorian gives details of atrocities and cites historic and contemporary genocides. Cleverly, he draws transparencies of genocides, attributing man’s inhumanity to man “when the world becomes indifferent” and when “images of atrocities” are forever in the news or on television.

The memory of Panian’s writing about his experiences can never be denied or forgotten. Dr. Gregorian states “…Memory cannot be assassinated…” Panian was not only a survivor, but a witness to the history that overwhelmed his youth. Gregorian reminds readers of the victim’s revelation of truth saying, “…We can never forgive and forget the suffering of all Karnig Panians…” Significantly, the memoir encapsulates a collective memory and responsibility of everyone touched by his suffering and message.

Clearly, Panian’s experiences comprised a chain of events similar to others, yet also unique. His stamina and courage as a five year old exceeded many who had similar experiences who were older than him. The deportation of the Armenian populace did not compare to any other minority of the Turkish Empire during World War I. Armenians were singled out, further removing them from their historic kingdom and territories once occupied by their antecedents.

Today, a plethora of genocide denialists and state historians of modern Turkey claim that the Armenians were evacuated from war zones for their protection. This assertion is baseless since historical documentation and eye witness memoirs have provided accurate information about their falsified rationale. Dr. Gregorian added in the Foreword, “…Truth cannot be denied.” The late senator, ambassador, scholar of ethnicity and presidential advisor Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York once penned these poignant words that can be applied to the denialists and falsifiers of the Armenian Genocide: “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.”

Young Panian witnessed the horrors of deportation. He saw members of his family and their friends die. His beloved mother perished in front of his eyes as did others in the caravan when they were forced to march with very little to eat and drink. She attempted to keep her children and loved ones fed as long as she had the strength. Although Armenians left many empires, they existed in history in a new land and maintained their status quo while managing to survive; however, the Young Turks did not give them options, and their extirpation was part of the Genocide of 1915 which was covered up by World War I. In Panian’s own words about Antoura,“…it was easy to die, and so hard to survive.”

Food was lacking and the children were very hungry, while medical assistance was negligent. They would escape in the middle of the night to gather food and vegetables from the local farms, taking risks and putting their lives in jeopardy. In their despair, fear and bleak situation, they rebelled against the Turkish authorities and their quest to Turkify them. If they were caught disobeying, they were severely punished; their bare feet were struck with clubs among other horrific torture methods.

The scope of the book covers a Foreword, Introduction, Panian’s memoir, Afterword and Acknowledgements. The Introduction is insightful for those who are unfamiliar with the events of the Armenian Genocide, World War I, Antoura orphanage, the Turkish leaders, League of Nations and other aspects of the entire era; Dr. Keith David Watenpaugh discusses the details without giving a long explanation of each area mentioned. He alludes to Panian’s story as a reflection of a later work by Holocaust survivor Primo Levi’s account of surviving the Auschwitz concentration camp.

In his memoir, Panian explains in detail the experiences and trauma he went through: Childhood, Deportation, The Desert, The Orphanage at Hama, The Orphanage at Antoura, The Raids, The Caves, Goodbye, Antoura and Sons of a Great Nation. The book was published in English on the centennial anniversary of the Armenian Genocide in 2015.

The author writes about the visit of Jemal, one of the three leaders of the triumvirate in charge of the Turkish regime, who visits Antoura. Jemal is the Minister of Marine. After the pomp and ceremony of his visit which the orphans were forced to take part at Antoura, Panian noticed a woman who remained behind after Jemal’s departure. Halide Edip was a well known Turkish nationalist and writer, and was principally responsible for instruction at the orphanage. Her father was a former secretary to Sultan Abdul Hamid. She was a feminist, activist and novelist.

In the time frame of World War I and the Genocide, she was a supervisor of Ottoman schools. Panian wrote about watching her stoical response when students were harshly beaten. He said: “Neither the teachers nor the staff members, – not even Halide Edip – batted an eyelid at the display of savagery.” After World War I, she became a political advocate and propagandist for Kemal “Ataturk.” She traveled to the United States and spoke to various college groups. She propagated the view that there were deaths of both Turks and Armenians which overshadowed the Armenian Genocide and the killing of other ethnic minorities in the Ottoman Empire. Edip began the cover-up and denial of the Turkish regime’s crimes which has continued to the present day. She was never prosecuted for her views or actions in the post-genocidal era even though she was responsible for transferring children from their Armenian culture and changing their language by using Islamization to eradicate their Christian backgrounds. Professor Watenpaugh explains earlier that Edip’s mission was to advance the Turkish state by converting children’s identities. He points out that the 1948 Convention pertaining to the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide explains: “Genocide means any of the following acts with intent to destroy, in whole or in part,a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: … Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” Clearly, she was guilty of war crimes against the Armenian people. The book reviewer thinks there should be no statute of limitations of criminal behavior or actions of people who perpetrate genocide against innocent people. Watenpaugh also makes excellent comments about the distinction of prewar Christian orphanages compared with those created by the Young Turk regime who killed the parents of the orphans to create state orphanages.

In the Afterword, Dr. Watenpaugh capsulates Panian’s final return to freedom and his relationship with the American Red Cross and Near East Relief (NER). He also describes orphans without a country and survivors from different cities of the Ottoman Empire and their unknown futures. Ray Travis, an unusual member of the NER and new American headmaster of an orphanage in Jubayl, Lebanon, welcomed the Armenian children to their delight. He had worked hard supporting the Armenians of Aintab.

Watenpaugh also mentions the contribution made by missionary Dr. Stanley E. Kerr, who made sacrifices in the city of Marash, circa 1920. Kerr was the author of “The Lions of Marash: Personal Experiences with American Near East Relief, (1919-1922).” For the reader, Dr. Stanley E. Kerr was the grandfather of Steve Kerr, head coach of professional basketball team the Golden State Warriors. Kerr’s father was Dr. Malcolm H. Kerr, an academic of Middle East studies. On a personal note, the book reviewer had a family member who was orphaned during the genocide and who was saved by Dr. Stanley Kerr. Years later, she saw a man crossing 50th Street and 6th Avenue in New York City near Radio City Music Hall and asked if he was Dr. Kerr. He replied that he was, and she said, “I was one of the Armenian children you helped [after World War I].” Dr. Stanley Kerr was well known among Armenians in the city of Marash.

Panian mentions many well known Armenians in the city of Marash. The writer discusses many other survivors and their successes, including the construction of NER facilities by Armenian refugees and orphans. Many survivors were assimilated in Syria and Lebanon who were aided by the NER which provided education. Later, Armenians found their transformation to Western society easier to cope with, although their peers had more difficulty. Essentially, as time lapsed, Panian was strongly involved in revitalizing the Armenian community. He was educated as an electrician, but followed his passion to teach at the well known institute of learning in the Beirut Djemaran. With civil war and strife in Lebanon and the Middle East, many Armenians have left, including Panian’s descendants; however, the memory of the brave children of Antoura will never be forgotten, along with many others from different locations.

Dr. Watenpaugh says the depopulation of Armenians has lessened the viable support of Armenian institutions including schools, newspapers and churches. The Armenian population is currently four percent of Lebanon’s population with the presence of the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia (the Holy See of Cilicia) in Antelias. The Western Armenian language is also threatened in Lebanon without a dominant Armenian population or economic resources; this is also true throughout the Middle East. The Islamic State, says Watenpaugh, has jeopardized the existence of non-Muslims in Deir al-Zor, Raqqa and Mosul. Armenian memorials and churches were destroyed without repercussions. Panian and Armenian leaders assisted in reconstructing the Armenian community. In the contemporary scene, writes Professor Watenpaugh, much has disappeared because of “hate, violence, and lack of … opportunities.” In sum, a community like Antoura says Watenpaugh “is an artifact” where survival took place. Armenians can never forget those who perished and those who survived for their eternal memory.

At the end of the powerful memoir, Houry Panian Boyamian, one of Panian’s daughters, expresses her acknowledgements. She reiterates her father’s love for his family, friends, students and teachers. She also describes her father’s love for his mother, who held a unique place in his life; she inspired him to devote his life to honoring her by perpetuating the Armenian culture, language and heritage. The entry is moving and informative for a wider audience to understand the legacy of Panian and others in Antoura during the 1915 genocide. In a final tribute of appreciation to all who supported the fruition of the new publication, she poignantly says: “…Karnig Panian’s legacy lives on in the younger generations, including his grandchildren… and great-grandchildren… ” It is her fervent hope that the book conveys her father’s will of tenacity and courage. The book certainly serves as a monumental contribution to witnessing the history of a genocide.

Thank you for the insightful and thoughtful review. I will order the book.

Hello Gary,

I’m not sure if you remember me or not, but we did some work together many years ago. I’m happy to see you still active, and I enjoyed your thorough review of Karnig Panian’s important book. I’m a big fan of Goodbye Antoura and assign it as a required reading in my sociology of genocide course. Panian tells a deeply moving story in simple, accessible language, and the response from students has always been very positive.

There is a straight line between the 1915-23 genocide of Christians in Turkey and the genocide of Yazidis by ISIS in Iraq from 2014 onwards. This is why this Mr Kanian’s testimony has contemporary relevance to the wider community as well as to Armenians. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam. (Gaelic for May He Rest In Peace.)