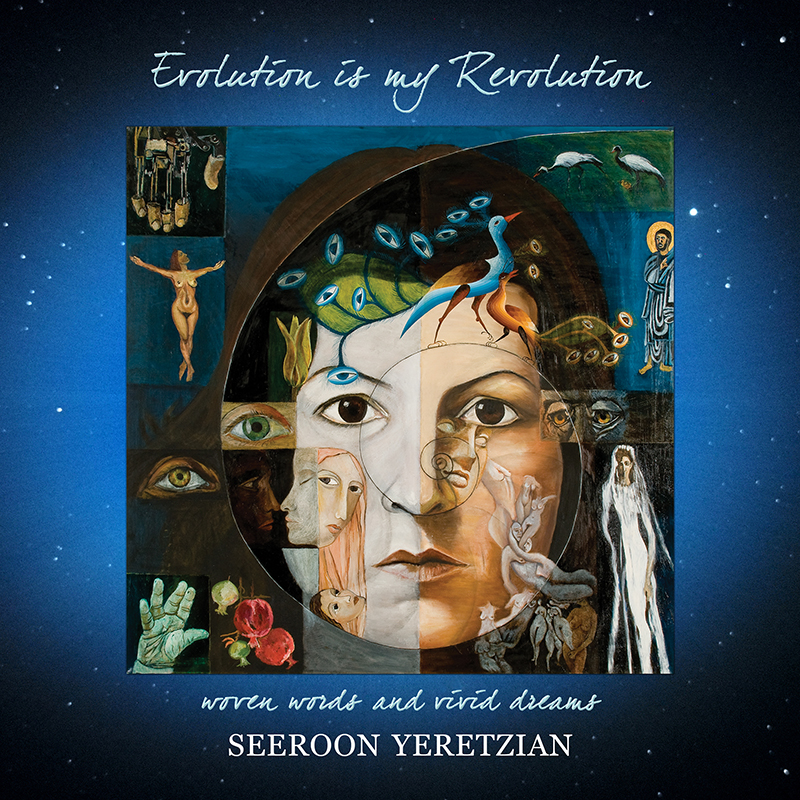

Ever since she was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease) in 2012, a disease that, in her own words, left her with a “live head on top of a useless body,” I have heard nothing but expressions of pity for Seeroon Yeretzian. “Meghk e Seeroone,” we all utter in disbelief. It is indeed impossible to reconcile the photograph of the smiling woman standing tall next to her “Words to the Reader” on the front page of her newly released book, Evolution Is My Revolution (ABRIL Books, 2018) and the real-life woman we witness today, “a chunk of useless garbage,” bent double, bound to a wheelchair.

Ever since she was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease) in 2012, a disease that, in her own words, left her with a “live head on top of a useless body,” I have heard nothing but expressions of pity for Seeroon Yeretzian. “Meghk e Seeroone,” we all utter in disbelief. It is indeed impossible to reconcile the photograph of the smiling woman standing tall next to her “Words to the Reader” on the front page of her newly released book, Evolution Is My Revolution (ABRIL Books, 2018) and the real-life woman we witness today, “a chunk of useless garbage,” bent double, bound to a wheelchair.

Evolution Is My Revolution was written on a DynaVox EyeMax computer, a miracle machine without which the book would not have been possible. Besides the 50 poems that give us an intimate look at the evolution of the artist, the volume includes Seeroon’s paintings, generously interspersed throughout. The intersection of image and text helps bring into focus the mood evoked both in the paintings and in the poems. The visual art also adds to the aesthetic appeal of the elegant volume.

Because she could no longer paint, Seeroon turned to writing to express “all my cries of happiness and sadness.” And although, by her own admission, a better painter than a writer, the poems do reveal a writer’s sensibilities. Seeroon has a gift for choosing the right word, the exact image, to communicate what she so keenly observes both within herself and around her. Her, “I wanted to travel across time…./But instead I crash-landed in present-day America, shot down as an alien,” delights us with its insight into the realities of our lives.

Seeroon can be playful and witty too. Lines like, “I am alone . . . I loved aloneness because I was married to an alone man, but together, two alones were not alone;” or “Life is a life sentence,” display a sensitivity to rhythms and to words. The very informal, almost conversational, tone of her poems helps draw the reader into her confidence. “The minute I went to bed, an incredible dream hit me;” or, “She had showered, crispy clean, and,/hiding under the cover, was waiting for her man,/to start their documentary in their bedroom-stage,” are catchy first lines. It is true that Seeroon’s writing is sometimes rough and may, on occasion, display an awkwardness in phrasing, but it never bores, a quality so sadly lacking in much writing. We all read to be entertained and if there is pleasure in the reading, some instruction will certainly follow.

Seeroon is very much aware of the horror of her situation, of her vijag, yet she has resolved not to let “the ALS cross” “diminish her purpose.” Rather than lament the life she could not live, the speaker in the poems is grateful for ‘the curse’ that helped revive her spirit, and that granted her “forbidden freedoms.” The disease did indeed awaken her mind’s inner dreams and liberated her from the shackles of taboos and religions. “It gives me the freedom to find myself,” she writes.

It is this newfound freedom that the book celebrates. With her super senses and a heightened imagination, the persona “un-roofs” the homes in her neighborhood and goes inside to expose the banalities of people’s daily lives, their marriages, their ownerships. In vivid, surreal dreams, she observes the Earth, “scarred and parched of water,” shaking with anger; trees dying and screaming for help; and “all living creatures overwhelmed with a feverish thirst.” She even comes face to face with God and has Him apologize for the suffering He has caused humanity. One does wish, at times, that her meaning was less directly spoken out.

It is this newfound freedom that the book celebrates. With her super senses and a heightened imagination, the persona “un-roofs” the homes in her neighborhood and goes inside to expose the banalities of people’s daily lives, their marriages, their ownerships. In vivid, surreal dreams, she observes the Earth, “scarred and parched of water,” shaking with anger; trees dying and screaming for help; and “all living creatures overwhelmed with a feverish thirst.” She even comes face to face with God and has Him apologize for the suffering He has caused humanity. One does wish, at times, that her meaning was less directly spoken out.

In the book, there is no trace of the woman who had been shy “all my life.” There is instead unrestrained joy in, “Freedom from ‘Who will say what?’/Freedom from hearing ‘Shame on you!’” “Meghk e Seeroone” has become irrelevant. Her “Don’t feel sorry for me,” still rings in my ear. I cannot help wondering, however, if the rejoicing is a mere mask to hide the pain, the frustrations and the humiliation of being “struck with the worst disease on Earth.” “Take my useless body, if that pleases You,/ . . . turn me into ash and blow me away like dust,/but/do not dare touch my spirit and my soul,” she writes in defiance. But in anger too.

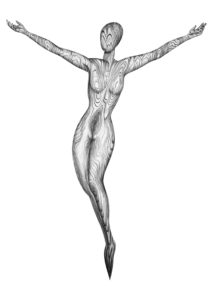

Seeroon can be frighteningly bold, and some will find her audacity to have us rethink the principles we take for granted irreverent, and the explicit sexual content of the poems, along with the nudity in her paintings, provocative. Let each judge for himself. I hope we all agree with her, however, that love is the only “true meaning of God,” and that a gentler, “life-loving and peace-loving” God, or God(dess), might well be a good replacement for a “cruel and punishing God.”

The artist lives with the promise of a new “god waiting to be reborn,” “and I deserve that,” she affirms. But the painful knowledge remains. Thinking of another tortured soul, she writes: “God is punishing me as He punished his Son, but/His Son mercifully was tortured for only one day./I wish I ended up on a cross and died in one day too.” Did the artist foresee her own crucifixion with her paintings of crucified women?

The book is a triumph. Our “Meghk e Seeroone” has dwindled to a whisper but, alas, it is still true of the woman who “does not deserve this!”

Be the first to comment