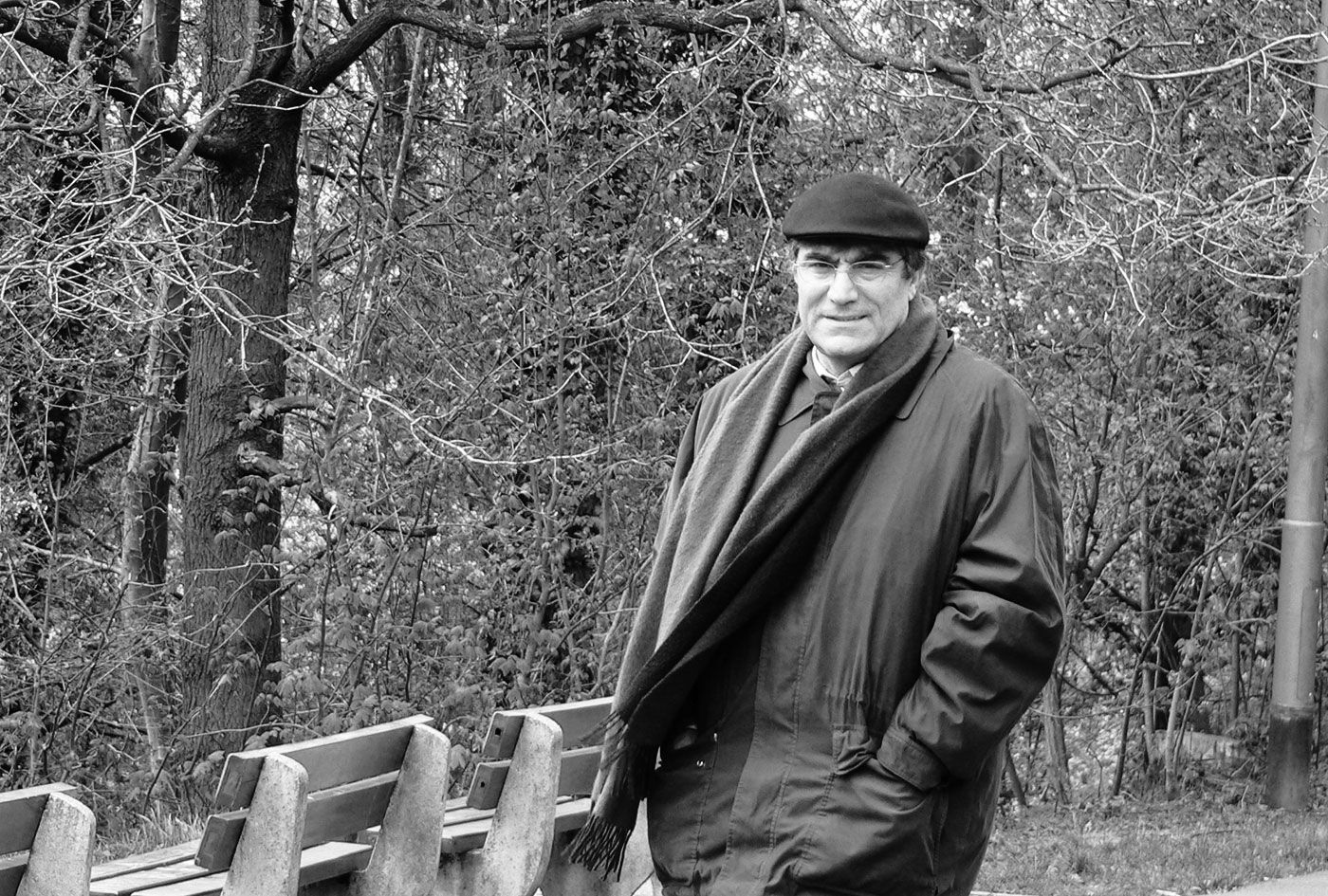

Remembering Hrant Dink

On January 19, 2007, a 17-year-old self-proclaimed Turkish nationalist killed Hrant Dink, the editor of Istanbul’s bilingual Turkish and Armenian weekly Agos, outside his office. News of his murder stunned people inside and outside Turkey.

The 53-year-old Dink was guilty of nothing more than having the courage to defend freedom of the press and to promote human rights and tolerance in Turkey. Turkish leaders harassed him and took him to court repeatedly on trumped up charges of “insulting Turkishness.”

In 2005, Dink was indicted under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code and was given a six-month suspended sentence, after which he received threats from Turkish nationalists who viewed him as a traitor.

Through Agos, Dink played an important role by promoting freedom of speech, democracy and human rights. He was also an advocate for Turkey’s small Armenian community. With great tact and consideration, Dink expressed his views. Without compromising the truth, he bore his own witness to the truth as he saw it, and for that reason, he became one of the prominent Armenian voices in Turkey.

For more than a century, successive Turkish governments have denied the fact of the Armenian Genocide and have vilified those who dared to speak about it. Dink tried to convince Turkish society of the necessity of an honest and critical encounter with the past. Governmental prosecution and nationalist elements tried to silence him, but they could not. He had the moral courage to stand for his principles, becoming our version of Martin Luther King Jr. — and thus, a champion of nonviolent freedom of expression in Turkey.

Finally, the Turks resorted to brute and fatal force, using a teenage agent of the state to silence him.

Years have elapsed since Dink’s tragic death, and I am left to ponder a few things. What made Dink the unusual person that he was? What was the core of his inner strength? What impact did his death have on others?

I have come to believe that what made Dink an unusual being was his sterling character. Character is the greatest ingredient in a human life. Wealth, prestige and intellect are admirable qualities, but without good character, they are like the spokes of a wheel with no hub to tie them together. Dink was a public-spirited, upright and good man who sought the common good. He was endowed with courage born of loyalty to all that is noble.

Dink’s character was not built automatically overnight but through Christian education. Dink received a solid Christian education at Badanegan Doon (boarding home) of the Armenian Evangelical Church of Gedik Pasha. This boarding home, where Dink spent eight years, was run by a young visionary and devout Christian leader by the name of Hrant Guzelian. This relatively older Hrant had a tremendous impact on the younger Hrant, as well as on the other borders, including his future wife Rakel Dink. The core of this couple’s inner strength was their Christian faith and their personal experience with Jesus Christ. They both became humble and loyal disciples of Christ at an early age, and together endured numerous hardships and challenges.

As a result of Dink’s heroic stance, he was able to put a decisive crack in the armor of that infamous Turkish law, and in his death, forced the Turkish government to consider changing it. His greatest legacy was the creation of a movement of intellectuals in Turkey to follow in his footsteps, becoming advocates of freedom of expression.

Dink’s death made many people in Turkey face the Turkish denial of the Armenian Genocide. Unfortunately, that denial is still a continuing crime against the Armenian people. Let us hope that the day will come when Turkey will acknowledge its crime against the Armenian people, as well as against humanity, and will make proper restitution.

May Hrant Dink’s courage, sense of justice, his dedication to the Armenian Cause and his faith in God inspire us and abide with us. May we resolve that his memory and legacy endure in our midst as an everlasting benediction.