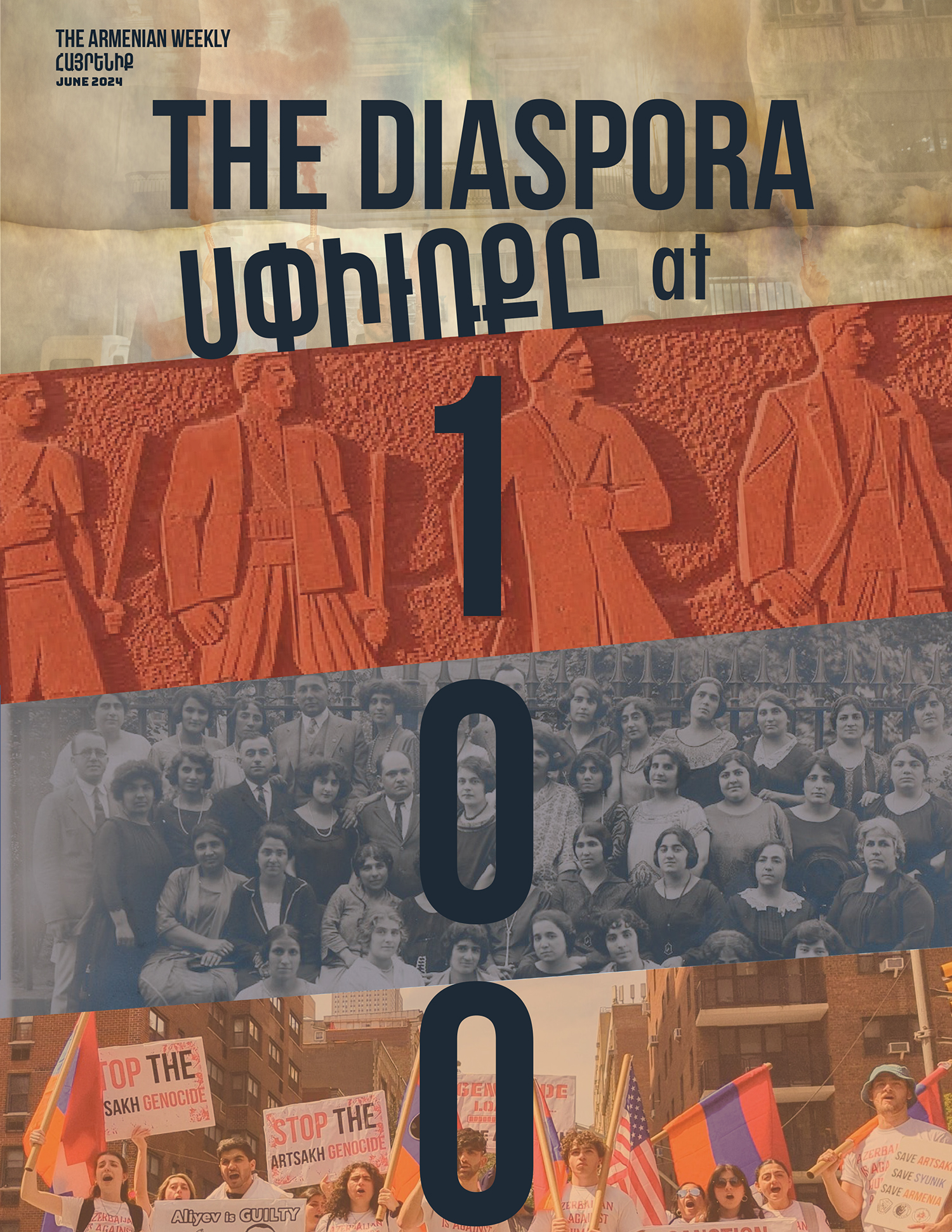

The following is the editorial introduction to the “The Diaspora at 100” special issue magazine. “The Diaspora at 100” is a landmark publication featuring essays by leading intellectuals, scholars and artists from across the global Armenian nation. The magazine in its entirety is available to read here.

The following is the editorial introduction to the “The Diaspora at 100” special issue magazine. “The Diaspora at 100” is a landmark publication featuring essays by leading intellectuals, scholars and artists from across the global Armenian nation. The magazine in its entirety is available to read here.

By Hayg Oshagan and Khachig Tölölyan

This volume originated from three impulses. The first was the desire to mark in 2024 the 125th anniversary of Hairenik, the major newspaper of the Armenian American diaspora, whose first issue was published on May 1, 1899. Additionally, we wanted to mark the centenary of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which ended Genocide survivors’ hopes of returning to their lost homeland and thus designates the formal beginning of the post-Genocide Armenian diaspora. Last but not least, these dates underscored the need for a contemporary assessment of the current realities of that diaspora, especially in but not limited to the USA.

We the co-editors neither wanted nor could achieve a panoramic, encyclopedic volume or a scholarly survey covering every aspect of even a single diasporic community, let alone of the global Armenian diaspora. We therefore chose a selective approach, based not just on some major communities but also on a sampling of ongoing processes that are reshaping the Diaspora — for example, contemporary cultural practices like music, or the changing aims and aspirations of pan-diasporic institutions (like the Church, the AGBU, the major political parties). Ultimately, this volume offers both an overview of our contemporary diasporan life, especially but not exclusively in the USA, and thoughtful discussions of many ongoing, transformational practices and performances.

In speaking of “the Diaspora” we are aware that the term marks not a single, united and concrete global community but rather a concept and a set of relationships. What actually exists in the world of daily life are ethnic Armenian communities with unevenly developed but always present “diasporic” characteristics; their links with each other and the Republic of Armenia constitute and define the capitalized Diaspora.

Details of the crucial relationship with the homeland are not within the scope of this collection of articles for three reasons. First, because we do not have the space and resources to tackle that issue in its entirety. Second, because the Republic of Armenia is currently engaged in a difficult, opaque process of redefining both itself (as a reshaped State/Petutyun) and the ways in which it will conduct its relationship with the Diaspora; that process is a moving target beyond our aims in this volume. Finally, we believe that the Diaspora cannot be treated simply as an appendage to the homeland; to the extent possible, it must be understood on its own terms.

The Diaspora is not a temporary, ephemeral phenomenon that is bound to end either by a wholesale return to the homeland or by complete assimilation. As one of us (KT) has argued in his scholarly work, what is at issue is not a return to the homeland but repeated re-turns; the diaspora turns towards the homeland in many ways short of complete immigration to and resettlement in Armenia, such as that which partially occurred in 1946-8. This wordplay concerning re-turnings is a way of indicating that in the past century the changing diaspora has turned towards the homeland in multiple ways, has engaged with it and will again (nerkaght-migration to the homeland; tourism and Birthright-type visits; financial assistance and frustrated investment; medical and myriad other forms of expert assistance; political advocacy for the Republic in the U.S., in the form of the ANC and AA, etc.). In the past 33 years since independence we have only begun to explore the many possible kinds of Diaspora-Homeland engagement. That will continue, but it will flourish only when we have fully acknowledged that the Diaspora is here to stay, and will continue to function and develop, with its communities, institutions and different localized operational and behavioral procedures. The Diaspora’s engagement with the homeland will persist, in changing forms that it is not our intention to pursue further here.

In this text, our writers explore the current state of some specific communities (Montreal or Aleppo, say) and many characteristic practices of diasporic political, institutional, social and cultural life. So the volume consists of short essays written by individuals who offer a quick overview of a community, a phenomenon or a practice, based whenever possible on their own personal experience and perspective. As co-editors, we have consciously avoided the homogenizing style and approach, the flattening out of experiences and perspectives. Here, clergymen who are also recognized as practicing intellectuals join professors and performers in offering a kaleidoscopic view of some aspects of both the U.S. diaspora and larger, transnational organizations and practices.

As an overview of the Diaspora at 100, we will make three fundamental assertions that in our view are foundational for the Diaspora. And although we did not ask our authors to discuss or develop these points specifically, they do form the basis upon which our opinion of the importance of the Armenian diaspora, and of this volume, is founded.

First is the affirmation that the Armenian Diaspora is a permanent reality. It is neither a temporary condition predicated on an eventual return to the homeland, nor a sort of purgatorial moment before assimilation renders it extinct. Previously, the Armenian nation has been diasporic in various times and places for hundreds of years. Diasporan communities change, grow, go into decline, Armenians move from one community to another, but the entirety of it, the diasporic nation, as it were, survives precisely because of a diasporan sensibility, we might even venture to say an identity, that allows and enables a people in motion to find new homes and found new communities. For every Beirut and Aleppo that Armenians leave, there is a Los Angeles and a Montreal that become new diasporan capitals.

Second, we know that there will be no return to Armenia for the vast majority of Armenians living in the Diaspora. This is not just based on the realities of emigration from Armenia, but also on the fact that there are no examples of full-scale return in comparable cases. Israel did receive large inflows of Jews at certain times (survivors of the Shoah; refugees from Arab lands after independence in 1948; emigres after the collapse of the Soviet Union), yet in recent years immigration to Israel averages 18,000 and emigration 45,000 per year. Half of the Jewish people remain outside the state of Israel. In the Armenian case, it makes good sense to think of “return” in other terms: visits that impress or transform diasporan consciousness, economic and cultural engagement, as well as virtual connections that lead to engagement always and commitment sometimes, rather than to physical re-settlement.

Our third argument is that the Diaspora is its own reality, with its own past history and its own future to chart. The Diaspora is not wholly dependent on the homeland state. Its sole purpose is not helping the Armenian state survive and prosper, important as that is, nor are Diaspora-Armenia relations always the defining element of the nature of the Diaspora. We need to give up the idea that the diaspora cannot exist for its own self, that it cannot be inknanbadag. To paraphrase the Jewish philosopher Spinoza, each existing entity must and does strive “to persevere in its being,” to preserve its own existence. We think of the Diaspora as an entity with its own agenda for the future, existing not just for the homeland, though always with it.

Our final point is a continuation of this thread, and asserts that the Diaspora needs as much attention, concern, commitment and investment as the homeland does. Over the past 30 years, since the independence of Armenia, accentuated by the liberation of Artsakh, pan-Armenian attention has been focused on the homeland. This has meant our intellectual as well as our emotional engagement and concern. This process of shifting our focus to the homeland has deprived the Diaspora of much needed attention. Given that possibly as much as 75% of our nation lives in the Diaspora, attention to national priorities necessitates an equal focus on the Diaspora as on Armenia.

The temptation to stage a competition for attention between the homeland and Diaspora should be avoided; this is crucial. No rational case can be made for the neglect of the homeland. And none can be made, or should be attempted, as regards the Diaspora. They are both critically important to the Armenian nation, for its survival and future. It is our concern that unless we focus more attention on the Diaspora, devoting to it the necessary resources and support, developing more realistic, hence more adequate theories and perspectives of the Armenian Diaspora, we will deprive our collective transnational reality of its capacity to survive and prosper.