Special Issue: Genocide Education for the 21st Century

The Armenian Weekly, April 2023

In the spring of 2019, a social studies teacher at the Bronx High School of Science (Bronx Science) asked if I would speak to her Holocaust class about our family’s experience during the Armenian Genocide. I was her second choice. She had already asked our daughter Sarinar who was enrolled in the class, but she had volunteered me instead. Probably due to its history and location, Bronx Science is a leader in Holocaust and genocide education. It even has a Holocaust museum which houses many artifacts of actual survivors who attended or were otherwise associated with the school. I had visited the museum on more than one occasion, and the assistant principal in charge of the museum and many of the teachers involved in Holocaust education knew me well. I accepted the teacher’s request without hesitation.

Speaking about personal or family experience seemed painfully boring for the exceptional students at one of the city’s most selective schools who were taking the class as an elective. It had to be a compelling class, with PowerPoint and all; otherwise it would be a flop, Sarinar’s social standing at the school would take a nose-dive and, worst of all, the subject matter would be disrespected. Though I have some unrelated experience in teaching, including as a teaching assistant in graduate school and training new analysts at a major Wall Street firm in infrastructure finance, teaching a class to high school students seemed out of my depth.

The horror stories I heard from my grandparents were no match for Instagram and Snapchat, media that excite this generation of teenagers. Without any formal training in pedagogy or history, I had to rely on my experience of understanding complex concepts and events that defy normal human activity. I also had the benefit of raising two children in New York City and having some idea of what could hold their interest. If a story had context and a coherent flow, it stood a fighting chance. The story had to be relatable; therefore it had to be through the eyes of one of their classmates. Also, it had to have positive elements so that it would at least minimally offset the unimaginable horror. I feared that if in the minds of a group of high school juniors and seniors there was no hope of a happy ending, I would lose them right from the start. At the end of the day, I had to draw a line from the Conference of Berlin to the classmate sitting next to them.

Fortunately, most of the students were familiar with history and geography thanks to previous classes. This was key for providing context that included 19th century Europe where human rights and dignity were becoming more fundamental and respected; the Ottoman Empire as the “Sick Man of Europe” in this space; the state of the Armenian nation and other religious minorities in the empire, focusing on the population as second- or third-class citizens with no real safety and security or economic rights; and lastly, the Conference of Berlin which shed international light on these problems and placed demands on Turkey to improve the condition of the Armenians and other religious minorities.

Perhaps the most challenging part was maintaining coherence in the story or trying to make “sense” of a decision to annihilate an entire component of an empire’s population. Why would a state commit genocide of its own citizens? Even our grandparents never gave us a satisfactory answer to this question, which would inevitably follow each session of the Genocide stories. “Because we were Christian.” “They hated us because they were jealous.” “They were bad people.” Their responses, which may have been partly true, were never fully convincing, and I was afraid that my students would also remain unconvinced. But a bit of history seemed to provide the answer. The Balkan Wars were particularly sobering for the Ottomans because they led to loss of territory following an uprising of the indigenous population. To the authorities, the writing was on the wall that the Armenians on the other side of the empire were next. If they eliminated the population, they would hold on to the land. It made “sense.”

Then came the challenge of finding something positive in a story about an abhorrent event. It turns out that even when humanity is at its worst, some people can be redeemable. We knew from our own stories of survival that sometimes it was thanks to the kindness, generosity or even courage of some Turkish or Kurdish people. My grandfather’s survival depended on the handouts of Muslim villagers after he had walked away from the caravan when he realized that the outcome was going to be horrible if he stayed. He and his younger brother became street urchins, begging and stealing for survival until the Near East Relief Foundation arrived. Many Holocaust survivors also have kind and generous Czechoslovakians, Hungarians and others to thank for their fate. Pointing out such parallels proves to be relatable for teenagers and makes the overall horror somewhat easier to process.

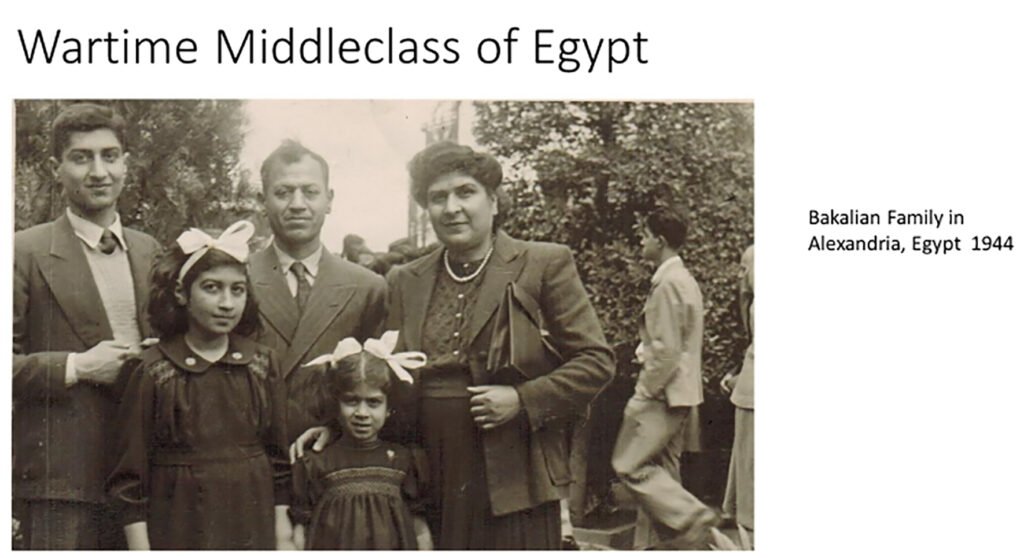

In a sense, the mere presence of their classmate among them illustrated the happy ending. But the long arc of deportation and its unspeakable details, an American orphanage in Greece and settlement and prosperity in Egypt made the story relevant. Then came repatriation to Soviet Armenia, where my grandparents viewed their survival as victory in and of itself, maintaining a positive attitude. My parents, however, could never adjust to Communism, forced Russification at the expense of our national identity and inheritance and were forced to leave – ultimately resulting in Sarinar as their classmate. Much of this rings familiar to New York City students, as many of them are immigrants or children of immigrants who also have experienced hardship.

Based on this general framework, I created a PowerPoint presentation with 28 slides. They began with a map of the Ottoman Empire, highlighted with the six cities and towns that were home to six of Sarinar’s great-grandparents, and ended with an image of her as a three-year-old at the Bronx Zoo. In between, there were bullet points covering each of the aforementioned components with accompanying images. I also addressed Turkey’s persistent denial. At the time, the US had not yet recognized the Genocide, but the current version of the presentation features the US and other governments’ recognition. In general, any involvement by the US, such as missionaries, relief organizations and recognition proves relatable for students, which is key for maintaining their interest.

The first presentation was for a combined group of Sarinar’s Holocaust class and interested students taking Advanced Placement (AP) Global History. Two weeks prior, the teacher had assigned readings that were recommended by the AP guidelines. The class was a success, and there were many thoughtful questions after the 30-minute presentation thanks to the students’ preparation. Several other social studies teachers and an assistant principal also attended, and we all had a meaningful conversation after the students were dismissed. The assistant principal suggested that I continue teaching the class, even though Sarinar was graduating. I agreed, but recognized another challenge.

Though I had taken great care to get the facts right, I’m not a historian and the material was not vetted by an expert. That’s when I reached out to Dr. Khatchig Mouradian to make sure there were no glaring errors. To my relief, I had no material errors, and Dr. Mouradian offered suggestions that would enhance the presentation, such as having more photographs and making sure that the story remained through Sarinar’s perspective, even though she would no longer be present. He also suggested that I expand my audience to schools other than Bronx Science, as genocide education is now part of the New York and New Jersey high school curricula. Again, I agreed.

Since then, I’ve taught the class in both New York and New Jersey. It is generally well received, and teachers appreciate the fact-based comprehensive nature of the class and the total absence of hyperbole. I typically will temper some of my comments with guidance from the teachers and always ask permission to mention some of the more graphic elements, like sexual assault. Preparation by the students seems to be essential; at a minimum, some knowledge of geography and history is vital. This brings me to my next challenge – a request to teach a class of middle schoolers in a New York private school.

Bravo, Mr. Khrimian! I recall fondly the many years you humbly volunteered your time to Bronx Science on our School Leadership Team and in many other capacities. I am thrilled to see you have brought your expertise and truly engaging manner to young people across our communities!

An excellent work Kevork

100% in agreement

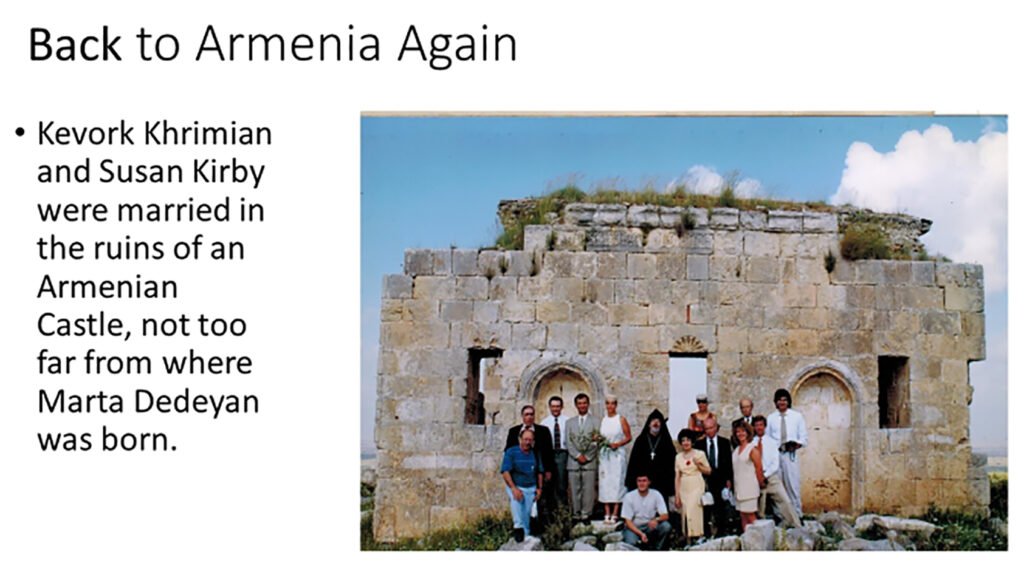

Kevork isn’t the necessity of time and realities on the ground that now we need to celebrate our weddings not in the ruins of past, (which doesn’t belong to us) but celebrate it in Syunik, in Goris, in Jermuk ?

Hi Kevork, What a great project you’ve undertaken. I expect your story will inspire others, too.

I enjoyed seeing the photo of your wedding party. It brought back lots of memories from ancient Armenia.