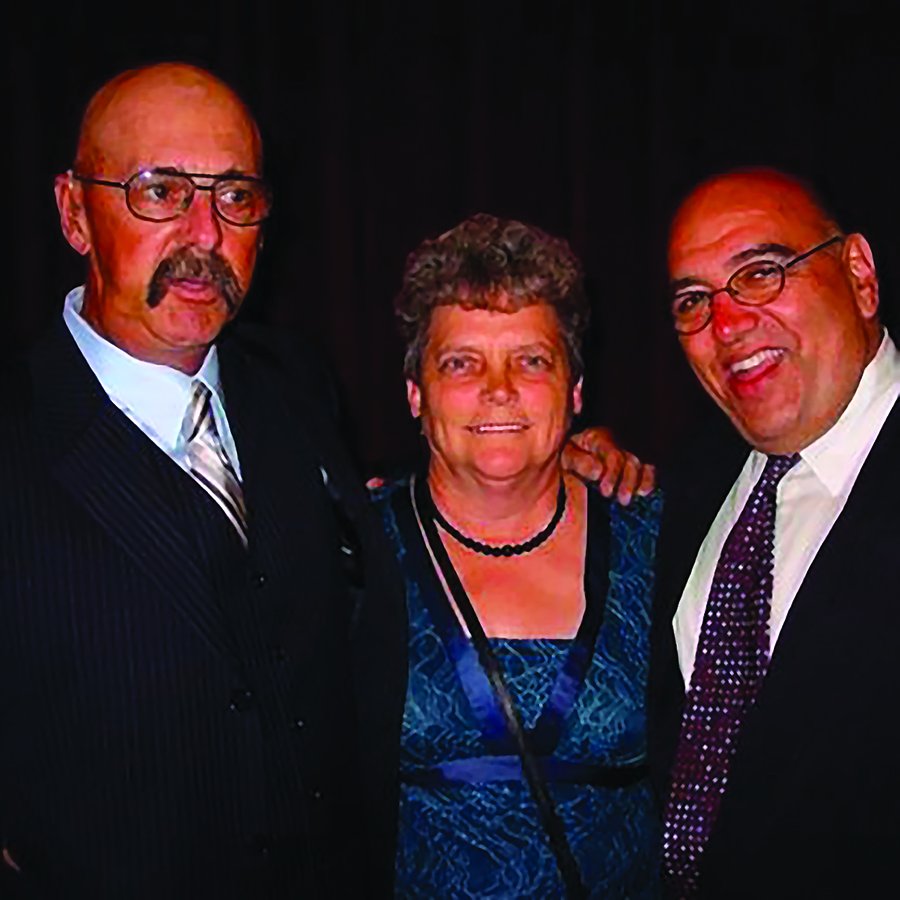

Michael “Manoog” Kaprielian never told his parents—Vartkes and Elizabeth (Dolbashian) Kaprielian—about any of it while they were alive. “It would have devastated them,” he said about his experiences in Vietnam in a conversation with the Weekly. This year, however, Kaprielian was featured in two “Veterans Voice” articles by Mary K. Talbot of the Providence Journal, the oldest continuously-published daily newspaper in the United States.

Talbot’s June 28 article enumerated the Vietnam veterans’ experiences marching in the country’s oldest Independence Day parade in Bristol, RI, for the first time after their return to the US following the war. After 40 years, “Vietnam veterans felt that it was time to organize, stand up and be proud of their service and sacrifice.” The servicemen returning from Vietnam came back to a country that did not visibly celebrate their homecoming. There were no ticker tape parades, no welcome home gatherings with balloons as they disembarked.

As they worked to gain recognition in Washington, DC and around the country for their service, the Vietnam veterans finally marched in the Bristol Fourth of July parade. Kaprielian, who joined his comrades in those early days of marching in the parade, remembered that they were relegated to the back of the procession, rather than up front with the rest of the military divisions. This meant that the Vietnam veterans were met with the spectators who remained until the very end after the other divisions had completed their march along the two-and-a-half-mile route. Uncertain how they would be received, the veterans were nervous but “found comfort being in the company of each other,” according to Kaprielian. Unexpectedly, the veterans were met with applause and respect when attendees rose to their feet as they passed by. It’s been several decades since that first parade which has become a place where, as the article states, the Vietnam veterans “could feel comfortable, even when our nation didn’t always feel comfortable with us,” Kaprielian said.

Independence Day, July 4, saw Talbot featuring Kaprielian and his lifetime of service in her “Veterans Voice” column. Kaprielian told the Weekly that the “transparency of the article may be rupturing the terra firma of silence toward my parents, family and the environs of my place of birth.” After 50 years of not speaking about his experiences, “lost now may be my sacrosanct world to gather myself among those who, from my infancy, may have held me in their arms,” he shared, referencing an emotional meeting with local Anna Najarian at an event held at Sts. Sahag and Mesrob Church in honor of then-Catholicos Karekin I. “The last time I saw you, your mother let me hold you,” she told Kaprielian, reminding him of the strength and warmth of his home community.

Kaprielian’s father Vartkes was a tank commander in the Battle of the Bulge during World War II; his grandfather and namesake was an Armenian Legionnaire. Having grown up with Kaprielian in the Providence Armenian community, we knew that he had served in Vietnam, but nobody could truly know what he experienced…and how it informed his continuing service to others, both in and out of Armenian circles.

The Weekly shares here some of his story as told to Talbot for the Providence Journal:

“I was in the rivers in Vietnam,” says Kaprielian. He served as part of the “Brown Water Navy,” working on inland waterways, disrupting enemy supply lines, from 1970 through 1971. It was a period during the Vietnam War when the United States was trying to withdraw and preparing the South Vietnamese to assume a larger combat role. Trying to encourage the South Vietnamese to finish the battle, American forces would “set up the South Vietnamese to finish the battle and get up their strength and courage to continue on,” he remembers. Unfortunately, “They would usually just fail and run out and we had to pick up and finish.”

Being able to spot the enemy was also a challenge during this period of transition. “It was confusing. We didn’t know who was friendly and not friendly,” says Kaprielian, who was captured one morning when he awoke in a restricted area to find his boat gone. If not for the bravery of a fellow American who rescued him, along with the grace of God, Kaprielian believes his life would have been over.

Even standards of honor and bravery were hazy. Toward the end of his tour, Kaprielian was involved in “a very big battle in which my little boat was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation” for their efforts along the Mekong Delta. However, “even though the Chief of Naval Operations involved congratulated us on awarding us the Presidential Unit Citation, they lowered it. They lowered all of the medals … that’s the way things were,” remembers Kaprielian. Military life during the Vietnam War played out much differently from the plots of war movies he had watched as a child where the heroes and the villains were separate and distinct.

At the end of his tour in Vietnam, Kaprielian left the unpopular war not knowing the reception he would receive upon his return to the States. “We didn’t want to openly say we were veterans. As a matter of fact, I separated from military service not through the normal practice of coming to Charleston, South Carolina, but asking for my separation in Europe. I separated in Italy with a voucher that was good for a year to walk into any military base to fly home. I didn’t have it. I just couldn’t face my own nation.”

Kaprielian put on a backpack and traveled Europe to begin processing what he had just experienced. He eventually landed at a base in Germany and flew back to the United States with long hair, a beard and no dress uniform.

Kaprielian’s journey back home would be a long one. “Vietnam veterans are a snapshot of America that just didn’t turn out all right and never made it into the family album,” he says.

In the days after the article’s revelations, Kaprielian offered some thoughts in an interview with the Weekly. “As a Christian, Armenian-American, humanitarian and Rhode Islander,” he said, “my reflection upon celebrating freedom and independence has evolved.” Kaprielian feels his life, which was saved through the bravery of Ron Currie of Maine (who passed away in 2006) “was purposed, to pay it forward, attending to disasters both natural and manmade including the terrorism visited upon the World Trade Center.”

When he returned to the US through Los Angeles in 1972, he was “embraced warmly by a cadre of Armenians” including Vahe Berberian, Ara Madzounian and Kevork Santikian, something he did not expect as one who was suffering the aftereffects of the ravages of the Vietnam War. “The Armenian community saved me, and it was at that moment that I dedicated myself to the Armenian community,” he explained. “It was never about me and my story.” Rather, Kaprielian has insisted that the focus be on those he has served.

Among Kaprielian’s vast experiences on the frontlines, one in the jungles of the Mekong Delta stood out to him, as it was a chance meeting with a fellow Armenian. Dale Doodigian, armed with an M-16, was patrolling the area with a German Shepherd when he ran into Kaprielian, who quickly recognized an Armenian comrade. Following their encounter, Doodigian was able to reconnect with family on the east coast after the war, another one of Kaprielian’s connections with a purpose.

Today, Kaprielian owns Ani Luxury Suites in Providence, an apartment building he renovated and where he has since provided housing to over 100 refugees, in addition to welcoming guests from around the world. He recalled the first refugee he ever welcomed named Uba, who had suffered unimaginable atrocities before arriving at his doorstep. She had come from Somalia in a wheelchair with a three-year-old. He likened her uncertainty about how others would view her arrival to his experiences as a newly returned Vietnam veteran. At the time, Kaprielian’s other tenants were scholars and highly regarded professionals, and he wasn’t sure how they would respond to the new member of their little community. He was pleasantly surprised. Some kindly provided diapers and clothing for Uba’s child, while a Japanese scholar helped with her wheelchair and laundry.

“Now I know what freedom feels like,” said Uba. Those words gave Kaprielian the clarity he needed to understand the meaning of his sacrifice and service, in his words: “to truly embrace our nation’s freedom.”

Manoog’s military pedigree extends back a little further on his mother’s side. The fedayee “Kayl Vahan” was a Dolbashian (Minas Dolbashian – born Palu-Havav).

God bless Manoog for his commitment to help

others. I have known him for decades but learned

so much from this article. He comes from a wonderful

family who in their own right are talented. So happy to

see his story being told.