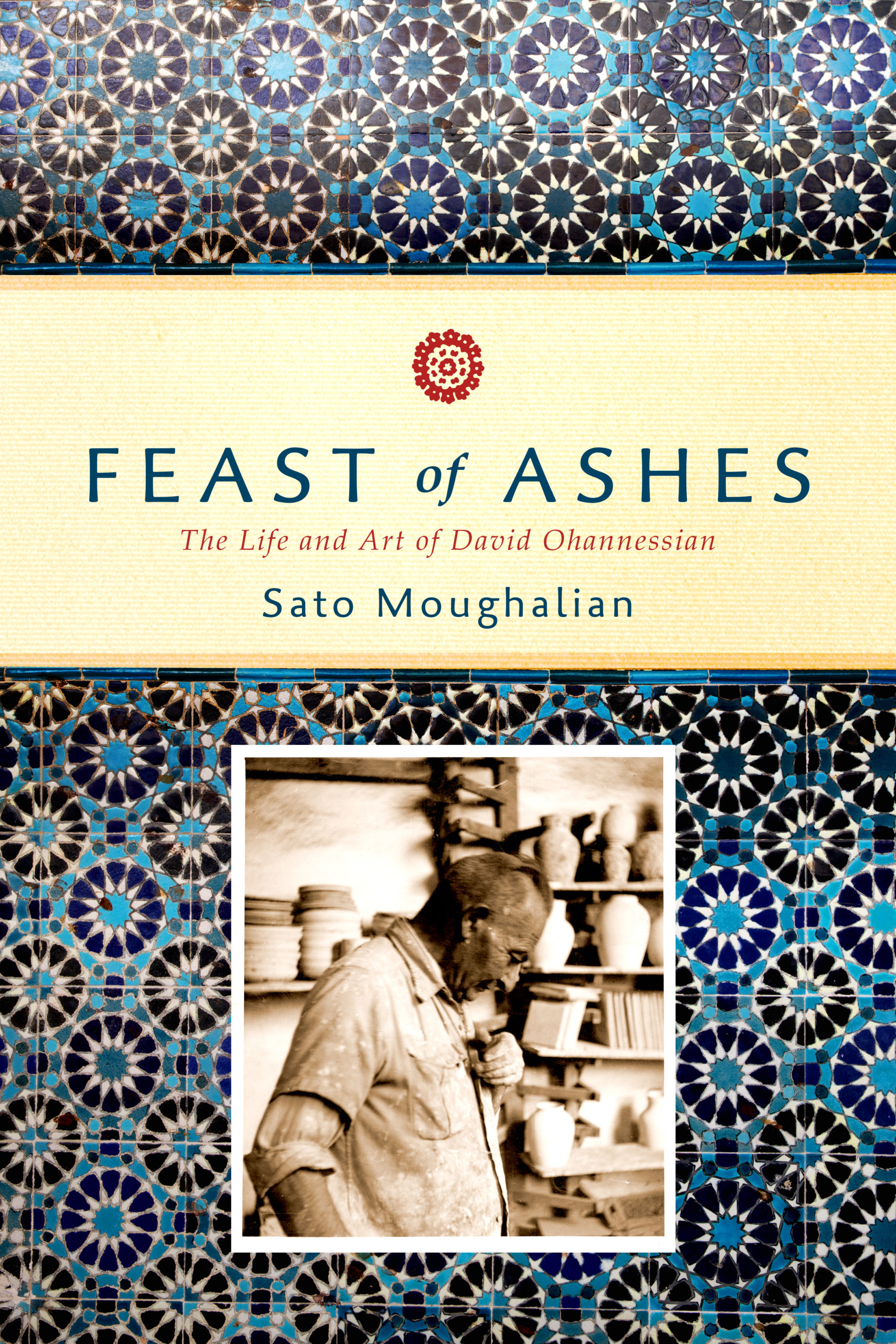

Feast of Ashes is the story of my maternal grandfather, David Ohannessian, who mastered the art of ceramic making in Kütahya, in Ottoman Turkey, in the years before the First World War. During the Armenian Genocide, he narrowly escaped a death sentence and, with his wife and young children, survived deportation to Syria. In 1919, he founded a new workshop in Jerusalem and established the tradition of glazed, painted ceramics and tiles in Palestine as a resident art there.

Today, that art is known as Jerusalem Armenian ceramics and has become a defining feature of Jerusalem. The tradition continues to thrive in workshops led by descendants of the other two families in the first generation of Kütahya-Jerusalem artisans—the Karakashians and the Balians, as well as other Armenian families who joined the Jerusalem trade in later years, the Sandrouni brothers, Hagop Antreassian and Vic Lepejian.

But long before I traveled the world in search of my grandfather’s traces and sat down to write the story of his life and art, I was an immigrant child in New Jersey, whose family fled the violence of Egyptian nationalism for the safety and promise of American freedom. I grew slowly into an understanding of our Armenian heritage and the legacy of my grandfather’s remarkable artistic achievements.

Feast of Ashes, the biography of David Ohannessian, begins and ends with my personal accounts—how I became determined to uncover the true story of our family’s exile and journeys and how I ultimately came to terms with what I found.

(Reprinted with permission)

Prelude

The Search

“EVERY PERSON HAS A STORY,” said my mother in her lilting half-British, half-Armenian accent. “It’s just a matter of listening and coaxing out the heart of it.” But at the prickly age of thirteen, I had absolutely no idea what she was talking about and often found her fondness for this kind of lyrical rhapsodizing most annoying. She was trying to explain something she had heard in her college writing class that day, something that resonated strongly with her. She sighed, puffing out her plump cheeks, and pushed her glasses up on her narrow nose before turning back to the textbooks sprawled all over the table.

This was the nightly scene of my 1970s adolescence in our small barn-red, white-trimmed house in the leafy New York City suburb of Highland Park, New Jersey. Both of my parents were attempting to replace educational credentials they had lost in their flight to the United States from the Middle East. Each evening, after an early dinner of cumin-scented beef or green bean stew, cooked in the way my mother had learned during her Jerusalem girlhood, my father would withdraw to his paper-crammed study on the ground floor to prepare for his next engineering exam at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

At my mother’s insistence, my parents had scraped together the down payment to buy that little house in 1963, just a few years after fleeing Alexandria and the burgeoning nationalism led by Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. “Egypt for the Arabs!” was the slogan they’d heard shouted in the streets of Alexandria as the 1950s ended. As my mother and father watched their Jewish and fellow Armenian Christian friends quietly disappear from their workplaces and homes, they realized that the time of relative safety had already run out. They used the little savings they had to purchase black-market Egyptian exit visas and prepared to leave with me, their baby daughter, in tow—all of us beneficiaries of an American immigration system that favored educated, English-speaking people trained in needed professions. An engineering job, arranged by a relative, awaited my father in the States.

An Egyptian lawyer they knew offered to bring their small valuables—inherited jewelry and some gold—to the airport and deliver them just before the flight so that they could avoid suspicion as they passed through the exit interview. He never showed. Arto and Pheme Ohannessian Moughalian climbed the stairs and entered the plane with me in their arms and $140 in my father’s pocket. Their meager possessions, packed into a few shallow wooden crates, were stowed in the cargo hold below. Once they were seated, Pheme wept, at the loss of her gold crucifixes and bracelets—handmade by her great-grandfather—and for the even greater bereavement of leaving behind every place she had ever known and loved. As the airplane taxied on the runway, my mother crossed herself, as she always did when beginning a journey.

In our living room, a white-painted brick fireplace faced the front door. On the mantel, high above the reach of a child’s hands, stood a lustrous pottery vase, about ten inches tall, covered with a vibrant cobalt blue glaze. Even in winter dusk, light bounded from its faintly dimpled curves. Large floral medallions in green and white filled the field, with stylized red carnations laced between them. Feathery leaves traced graceful arcs around the flowers. Turquoise and white diamond figures circled the neck of the vase, strung together with tiny knots of red glaze that piled up in relief.

We never ever put flowers in the vase, and from that I learned that sometimes objects exist just to be admired. On the rare occasions my mother took it down, and the rarer occasions still when I was allowed to hold it, I was always surprised by its heft. The glassy surface stayed cool to the touch. I ran my hand along the inside and traced the smoothed imprints of fingers, which had left furrows in the clay as the vase was shaped on the potter’s wheel.

“Your grandfather made that,” my mother said.

David Ohannessian, her father—Baba, she called him. This was as close as I would come to touching my grandfather’s hand. I had never met him; he died before I was born. But this vase, with its elegant form and dancing flowers, which had emerged so many years earlier from the ashes of a far-off kiln, survived my mother’s journeys, from her native Jerusalem to Damascus, Cairo, Beirut, Alexandria, and finally America. It was always present and watched over us.

Brooding, threadbare carpets with tribal icons in shadowy reds and blues covered our wooden floors. An antique mahogany and ivory-keyed upright piano, given to us by the aptly named Miss Goodhart, an elderly librarian friend, commanded one wall. In the Middle East, a piano in the living room was a sign that a family valued culture, especially European culture. In our case, in America, the piano’s very bulk and ungainliness was a signifier that neither it nor we were going anywhere anytime soon.

Most evenings, I knew I had to leave my parents to their separate silences and went upstairs to my own room. Like my mother, I loved to read. I had decorated the inside of my bedroom closet with deep brown corkboard and haremed up the space with an Indian print bedspread swathed around the clothes pole in a hippie version of a desert tent. A reading lamp and pillow were everything I needed for the hours of solitude I spent inside. Books were our family’s common ground. Books bound us together, surrounded us in every room. Books provided a limitless escape from the confines of our daily lives.

…..

We studied the Holocaust in school. Every few years there was a screening of Night and Fog, the 1955 French film—one of the first documentaries to show extensive footage of the concentration camps. My mother explained that there had been terrible Armenian massacres with huge deportations as well. But she rarely spoke of it at any length; she was choked by anger and sadness whenever the subject came up. Years afterward, I read that as many as one and a half million Armenians had been slaughtered or forcibly marched from the regions they had historically inhabited in the Ottoman Empire, only to die of starvation or disease in the Syrian desert between 1915 and 1917.

As a young child, though, I had only the vaguest understanding that my own family had been swept up in these catastrophic events. At my Jewish friends’ homes, on their parents’ bookshelves, certain titles consistently appeared: The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, QB VII, Judgment at Nuremberg, Night, Inside the Third Reich, Treblinka. At twelve or thirteen, I started compulsively borrowing these books from the library. As I read them, I often felt a familiar surge of terror but didn’t understand why. I tried to speak to friends and their parents about the nearly incomprehensible acts the books described. All they would concede was that an uncle had perished, or that a parent or sister had survived. A few even bore tattooed numbers—usually concealed, but sometimes visible in an unguarded moment. The books were right there, bursting with answers, but no one, I discovered, wanted to talk about his own relationship to the subject.

During those years of focused reading in the 1970s, I also began to notice a ghastly wasting disease in a few of my schoolmates, often after their parents’ divorce or some other major rupture. First, they would pick at their food and grow thinner. Then they would become distracted. Skin wizened, bony outlines emerged. Tufts of fine down appeared on their cheeks and arms. Usually, hospitalization followed. We learned that this illness was something called anorexia nervosa. Years later I wondered: were these young women suffering only because of traumas in their own lives, or were they showing a kind of unconscious loyalty to the anguish of their ancestors? Why in a time of such relative ease and plenty would they set themselves on the road to death?

Neither of my parents was very tall. At my full-grown height of five feet four inches, I towered over them both. My mother had copper-colored hair, which faded but persisted in its redness over the years. Her natural condition was roundedness. “We Ohannessians tend to put on weight,” she would say, with a matter-of-fact cheerfulness in that otherwise gamine-obsessed era. My father had wiry black hair, a protruding nose, spoke hesitatingly and much less often than my mother, with her rapid and highly inflected staccato. He had learned a total of seven languages in his native port city of Alexandria, but spun his sentences very slowly, punctuating them with uhs. He cleared his throat or rubbed his knees to gain time. He had a lifelong passion for the pure sciences and achieved a kind of ecstatic oblivion while immersed in a theoretical physics book. Once, he dutifully escorted my American-born, baseball-loving brother, David, to an Old-Timers’ Day game at Yankee Stadium. Thirty-five thousand fans thundered to their feet and roared cheers when Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio, and Phil Rizzuto strode onto the field. The nine-year-old boy glanced down at his seated father, deep in the throes of quantum mechanics.

My mother’s superb cooking and hospitality took flight at holiday times with skewers of marinated lamb kebabs grilled with herbed onions, peppers, and tomatoes, garlicky yogurt salads, butter crescent cookies, crispy cheese-filled phyllo triangles, raisined pilafs, cumin-scented ground beef kuftes, stuffed grape leaves, and lemony charred eggplant dips that bit the tongue. We were banished from her kitchen as the house filled with aromas that brought on ravenous appetites and later in the day, waves of laughter during lively conversations. She would take the seat at the head of the table, my father next to her. Mmm! she would cry out after her first bite, which always came before the guests had even finished passing around the dishes of food. “This is delicious!” The cuisine was alluringly exotic and also a redeeming counterpoint to our ordinary condition of “otherness.”

On quieter nights, my mother’s buoyant exuberance might deflate into a kind of bleak despair. As I was growing up in that little house, I occasionally witnessed my parents lose their grounding in the everyday world. They sometimes burst into a rope-veined agitation, seized by some specter of unutterable grief, dissociated from their normal selves. These storms were terrifying and we would never talk about them afterward, but they would pass. Not much of it made any kind of sense to me. How could I know, absorbed as I was by music, boys, my own all-too-frequent door-slamming rages, and the rambling 1 a.m. conversations about the nature of the universe on my newly installed private phone line, that in my own family’s living memory there was a time when the freshly washed laundry I took entirely for granted was an unimaginable luxury? That a knock on the door in the middle of the night could mean the end of life as we knew it? That some neighbors could save our lives while others might destroy them?

By the time I left for college, I had met many people who had a direct connection to the Holocaust. Some had grown up in the shadow of their own parents’ childhoods in concentration camps. Others had parents who threatened to disown them if they married a Gentile. As a child in 1939, the husband of my recorder teacher, an esteemed Rutgers professor himself, had sailed on the German ship M.S. St. Louis, which carried Jewish refugees to Cuba and then Florida; most were turned away and sent back to dark fates in Europe. One girl was a member of her father’s second family, the first having been murdered by Nazi hands.

My mother told us that her parents had been exiled from their home in Turkey, but the details of the story remained indistinct. While I yearned to know more about our family’s past, especially after having taken a college course in “Armenian Civilization,” where I was introduced to the term “genocide,” I also dreaded what I might learn. Over time, it began to feel as though there was some kind of high-voltage fence encircling the facts of our lives. I wanted to get closer to knowing what had happened, but mostly it seemed safer to keep away. I did know some specifics, of course. I knew that my grandfather had been a ceramic artist from Kütahya, an Anatolian city famous for its tile work, in what had been the Ottoman Empire, and that he was an acknowledged master of its then four-hundred-year-old tradition. Sometimes, I would read a reference to him in an art journal or newspaper. One relative or another would proudly circulate the clipping.

Eventually, my mother revealed that he had been arrested and sentenced to death in 1915 but had somehow been released from prison. He, my grandmother, and the first three of their small children—the ones that had been born by then—had been deported toward the Syrian desert of Deir Zor in 1916 and had ended up in Palestine, where my grandfather replanted his art in Jerusalem. My mother also told us that she and most of her family had fled the terror of bullets and explosives in her beloved native city of Jerusalem and had become stateless in 1948.

But my grandparents had survived. And my parents had survived. They had made a giant leap of faith and traveled to yet another foreign country in the hope that they could root themselves in a different kind of society—one that was free of constant threats, upheavals, and loss. I came to see that my grandparents’ fundamental task had been to keep their family alive. Not only had they done that, heroically, but they were also able, somehow, to take a centuries-old art form and give it a new life in Jerusalem—a tradition that continues to flourish today. They went on to create a family of seven children, each of whom would add his or her gifts to the world.

In time, those offspring would disperse across the globe and, in turn, bring new lives into being. They would become teachers and librarians, chemists, poets, and artists themselves. They and their children, like the children of so many immigrants, would bear the burdens of dislocation and unmourned losses, but also embody a ferocious desire to create order and beauty and to search for knowledge and a place in the world.

…..

My mother derived enormous satisfaction from her teaching and made enduring and devoted friends. After too few years in her job, she was stricken with the debilitating rheumatoid arthritis that tightened an ever-narrowing circle around her physical life and compelled her to take medical retirement in 1983. She grew calmer and more contemplative. In the mid-1980s she began to think more about her past. The death of her younger brother in 1988 spurred her and her sisters into action; they began collecting oral histories from everyone who had known their parents. Perhaps she felt her own impending mortality and wanted to leave something tangible behind.

In 1992, three years before she died, my mother finished notating fifty pages of carefully collated family stories. She made copies for my brother and me, and for all of her fourteen nieces and nephews. At last we had a record of the collective memory of her generation: the handed-down dialogues of our forebears, stories of my mother’s parents’ birthplaces, their courtship and marriage, my grandfather’s achievements, the brutal exile from Turkey, and their new life in Jerusalem. The stories were veiled in loving language. Descriptions of the cruelest episodes were softened with the patina of distance and time. As the illness consumed her body, she increasingly struggled to breathe. In her final days, the weight of unspeakable grief I had watched my mother bear throughout my childhood metamorphosed into a radiant, otherworldly longing to see her parents once again.

During my first years as a professional flutist, I’d gained experience in performing and developed close relationships based on the shared joy of making music. I learned to embrace the hours of daily practice—smoothing out a scale, using focus and repetition to chip away the distance between an idea in music and its actual result in sound. Those efforts bore rewards in chamber music concerts during which we musicians might revel in the bliss of perfect communion, synchronizing swells and falls, rushing forward or lingering on a note in complete coordination. In music—in the throb of a tone, the power of an attack—I found a channel for intense feelings of love, yearning, and loss, emotions that I could not express or even identify in words.

Eventually, my parents had abandoned their well-intentioned but futile pleas for me to become a doctor, lawyer, or in short, to enter any “real” profession. By my early twenties, I began to travel as a musician, playing concerts and seeking out architecture and art while touring. I had demanded this kind of life, and little by little I was finding a place for myself. But the big questions remained unanswered. How did I become the person I am? Where did these stubborn drives toward art and music come from? Who were my people? Where exactly did we come from? And on whose shoulders did I stand?

My mother had always tried to fill in the gaps, recounting to my brother and me episodes from her childhood and excitedly pointing out towering figures in Armenian culture: William Saroyan, Arshile Gorky, Mesrop Mashtots, Nerses Shnorhali, and of course, Gomidas Vartabed, whose large framed portrait graced our living room wall. Once, while I was in college, St. Vartan Armenian Cathedral in New York City announced a performance of the world-renowned Soviet Armenian string quartet named for the musicologist-composer, giving the audience only a few days’ advance notice. My mother had insisted that I attend with her, paying me the lost wages from my Sunday bookstore job. For her, Gomidas and his music represented a profound connection not only to her Armenian identity but also to her father, to her earliest memories of his voice raised in song, and to the many stories he had told her about meeting and hearing the revered Armenian priest and musician. During that concert, I too fell instantly and passionately in love with the poignant melodies in haunting settings and immediately began to incorporate Gomidas’s music into my own repertoire.

Still, I craved a deeper connection to my artist grandfather. I read anything that mentioned him or his work and discovered that some art historians in the 1980s had begun to write about the establishment of the Armenian ceramics tradition in Jerusalem. As I pored over museum catalogues and articles, I saw that a significant number of biographical details were incorrect. Dates of his birth and death were off, the particulars of his arrival in Jerusalem distressingly incomplete. These writers were working with the materials available to them, and I began to understand that history, as it appeared in books, was not always a recounting of what had actually happened—it was the writer’s own version of the story of what happened.

Some intriguing books and papers about my grandfather’s art appeared in the 1990s and 2000s. From them, I learned more about the early years of the British Mandate in Jerusalem and the way in which my grandfather’s mastery of an old ceramic tradition intersected with the need to restore the badly dilapidated Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, a sacred Islamic monument covered with Persian and Ottoman tiles. These texts contributed to the story of David Ohannessian and his work and were built on the writings that had come before. They fueled an urgency in me to try to discover more.

Throughout my childhood, a 1916 book called The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire lay buried on a shelf in the dimly lit upstairs hallway. Four days after I finished high school, I’d loaded up a borrowed station wagon, eager to depart for New York City and the adventures that lay ahead. As I prepared to leave my parents’ home for good, at the age of seventeen, my mother pulled me close, kissed my cheek, and then passed the book into my hand. For decades, it remained untouched on my own bookshelf, moving with me from apartment to apartment, like an undetonated bomb, waiting for me to find the courage to confront what it contained.

In 2005, ten years after my mother’s death, I finally took a deep breath and opened the volume. Inside the mottled leaves were reports from Armenian Genocide eyewitnesses—British, Italian, and American diplomats, German missionaries and teachers, Danish nurses, and survivors. Page after page recounted marches, massacres, forced conversions, rape, torture, and assault. In the restrained language of the First World War era, Armenian women were “teased,” “ravished,” “outraged,” “ruined.” Armenian men were “flogged without mercy,” “horribly mutilated,” “put to the sword.” These were my people.

* * *

ON APRIL 20, 2007, I bid on what was described as an “Iznik-Style Pottery Bowl, Kütahya, First Half Twentieth Century” in a Christie’s London auction. The inside of the half-round form had intense greens and blues with a central lobed medallion that by then I recognized from my grandfather’s classic design vocabulary. On the outer surface of the bowl were vines and the same stylized red carnations I had admired as a child. Two Armenian alphabet letters were painted on the bottom, under the glaze.

I had stumbled on the auction catalogue by accident and decided to try to buy the bowl as a totem or a kind of symbolic gift from my grandparents to me. I liked the idea that I could build a bridge between generations by “repatriating” one of what was possibly my grandfather’s works. After a nerve-rattling 5:30 a.m. phone call from the London bidding desk, a few tense moments straining to hear what was happening in that sales room on the other side of the Atlantic, and then ninety harrowing seconds of bidding, the bowl was mine!

I had also inherited the beautiful blue vase from the mantel of my parents’ house. When the newly purchased bowl arrived, it looked right at home. In fact, the two pieces seemed to come to life. They urged me to find more of their relatives.

One afternoon, after a rehearsal in her apartment, composer Eve Beglarian and I were drinking coffee and exchanging family stories from our shared Armenian heritage. “You know,” she said, “you are one of the lucky ones. Your family left breadcrumbs behind.” She pointed out that unlike many other children of displaced people, my family had artworks that had survived our various upheavals and held some of the threads of our story. If only I could find more, document the circumstances of their creation, and perhaps trace my grandfather’s footsteps, maybe then I could satisfy the old hunger to connect with my family’s past and resolve the multitude of disquieting and unanswered questions.

Later in 2007, my cousin David Donabedian gave me a document written by our aunt Sirarpi Ohannessian, who had died in 1999 after a series of strokes. She had left her longtime home in Washington, D.C., when she first became ill and settled in Los Angeles to be closer to her sister Mary. Sirarpi was the eldest of David Ohannessian’s seven children, an applied linguist and researcher. The eight-page record she left behind included a brief biography of her father and the lineage of his ceramic tradition. Tantalizingly, it also contained a list of his monumental ceramic installations in Jerusalem, Istanbul, Konya, Kütahya, Lebanon, England, Ireland, and France. She had compiled the list in Beirut in 1952, while her father was still alive, but some of the entries contained only minimal descriptions.

I began to wonder if these works still existed today. If they did, would it be possible to find them? Would the stories my mother had preserved provide more clues to their whereabouts? Could I follow the trail of these “breadcrumbs” and do the serious detective work needed to find a fuller history of my grandparents’ lives and the ceramic art that my grandfather had founded in Jerusalem in 1919? And could I learn to understand the historical forces that had shaped my family’s experience and attempt to see the world as it might have looked through their eyes? Would there be some reconciliation, or even redemption, for their suffering, along the way? Over the next months, these questions seized my attention and creative energies.

I called and emailed my cousins, hounding them for any old records, photos, or letters they might have in their possession. Documents began to trickle in. In September of 2013, my cousin Armen and his wife Jean Markarian were cleaning out their garage in Los Angeles and unearthed the mother lode: the box of archival materials that our aunt Sirarpi had painstakingly preserved. Inside were stencil pattern designs, original drawings, account books from Jerusalem, travel records, letters in Armenian, Turkish, Arabic, and English, notebooks with ceramic forms and designs, photographs of completed installations, calling cards, articles, catalogues, glaze recipes, British Mandate documents, proposals, and even kiln designs. They express-mailed the carton, and I opened it to find a wealth of clues that began to answer all sorts of questions about our grandfather’s life and work.

A few weeks later, Jean was in New York. We met for dinner at a favorite Greek restaurant near Carnegie Hall, and she handed me a shopping bag with a bubble-wrapped object inside. “We found something else in the garage,” she said, “and I think it belongs to you.” Underneath Aunt Sirarpi’s buried trove of papers, she and Armen had found a luminous blue tile with an Islamic inscription—a product of my grandfather’s workshop in Jerusalem—framed in gold.

She pointed out the faintly penciled inscription on the back:

for Sato Moughalian

from S. Ohannessian

Fourteen years after her death, Aunt Sirarpi’s legacy had been handed to me.

I saw her bequest as a sign that I had to keep following the trail. I had to seek out and tell my grandfather’s story.

In a sense, it is my story too.

Wow! Thank you. We lost our best and brightest and their gene pool in 1915and it has taken a hundred years to rebuild the Armenian intelligentsia. It is the grandchildren and the great grandchildren filling that void. Again… thank you.

Great story – so glad you pursued your grandfather’s story for all of us. My second cousin is a Mougalian, so we were particularly interested in this book. My elderly Dad was amazed by the photos in your book also. Thank you!

Helen Knar Cirrio, thank you so much for your comment and for sharing the book with your Dad–that was very heartwarming to read! Moughalian is not a very common name, so maybe your second cousin and I are related.

I was captivated and touched by your wonderful article. Reading your book I also discovered that your grandfather was born in Mouratchai, in the province of Boursa. My father Sahag Sinanian was also born in Mouratchai in 1903. From this large Armenian village, only my father and his uncle Sinan Sinanian survived, and eventually ended up in Lebanon. Thank you very much for shedding light on the history of this village. Much appreciated, I wish I had more information and more detailed of the history and origin of this Armenian village who initially came from the Armenian Highlands as briefly mentioned in your book.

Thank you very much, Stepan Sinanian, for your kind words. At some point, I will write more about the village, since during the research I found more than I was able to fit into that chapter. There are some endnotes that cite articles and documents I found, and I’d be happy to be in touch directly.

Hi dear Saro, my friend Noushin Framke sent me this article long ago that I just Des covered tonight and read with nostalgia!

Your mother Fimi, a beautiful lively red head was a few classes ahead of me at the Jerusalem Girls’ College. Her beautiful sister Mary was one of my teachers in seventh grade and the eldest sister Dirarpi was my mother’s friend. Their brother I think his name was Ohanes married our YWCA British swim teacher Miss B.. her family name started with B oh my gosh I think it was Miss Burns? My parents Haroutune and Mary Boyadjian in Jerusalem.,

We’re friends with the family. My father taught at St George’s School and in 1948 when the British left Palestine he was the first non British headmaster..

congratulations on your career as a flutist. I am a painter and have a website :- lucyjanjigian.com and DVDs in You Tube!! I lived in NJ till six years ago when I moved to CA to be near my daughter!! I got so homesick and it took me back to JGC DAYS!!

Thank you and please get in touch . My phone:- 201-294-0939

Would luv to chat with you. I was very sorry your mother suffered so much with RA..

Salaam with Best regards and luv, Lucy