From the December 2019 Special Anniversary Magazine Dedicated to the 120th Anniversary of the Hairenik and the 85th Anniversary of the Armenian Weekly

The Armenian Diaspora was forming long before the genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire nearly decimated our nation. Its beginnings were the entrepreneurs, traders, students, and the adventuresome who settled beyond their homeland—some permanently and others for varying periods of time. The process was accelerated when the survivors of the genocide were mercilessly cast adrift from their ancestral land. Where they went to rebuild their shattered lives was more a matter of chance, than by design. For many, humanitarian organizations determined their final destination.

One country that had attracted Armenians before the genocide was the United States, especially the northeastern region, where coastal cities such as Philadelphia, New York and Boston were important points of entry.

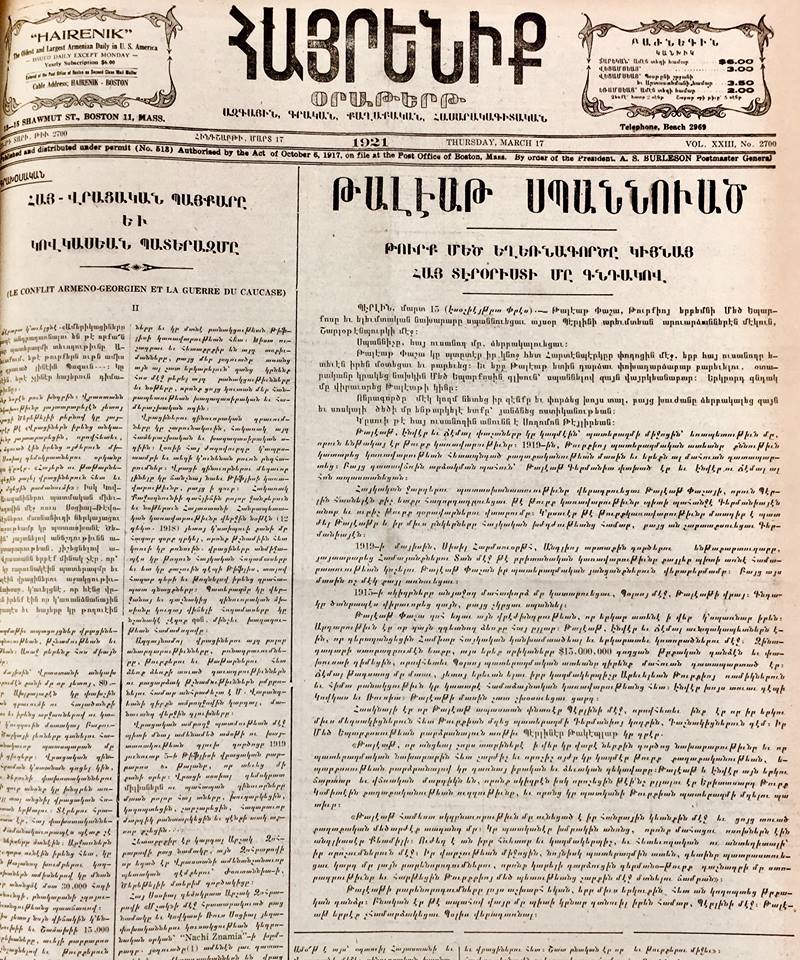

It was in New York that the Hairenik was first published in 1899. Although that city can claim birth rights to the Hairenik, its offices were moved to Boston the following year. In 1986 the Hairenik relocated to a newly constructed building in Watertown, a suburb of Boston, where it remains to this day.

It is not possible to appreciate how traumatized these survivors were. Thrust into a new environment, separated from family members and lifelong friends, their world suddenly shattered. Few, if any, ties to the past remained. Their future was a blank slate. Only time could tell what would be recorded. For most, there was little understanding as to why such a calamity had fallen upon them. Many were haunted by unspeakable experiences they had endured which they re-lived over and over again during the quiet of the evenings. Could it have been any worse? Not likely. Yet their greatest concern was not about self, but about the fate of missing family members and friends.

As the first wave of survivors reached the U.S., the Hairenik had already become a well-established publication. The fact that an Armenian language newspaper was being published in this foreign land could not help but buoy the spirits of the survivors. The Hairenik served as a vivid reminder that they were neither “lost” nor “forgotten.” Rumors were rife and information was scarce. This was a transformative period not only in their personal lives, but in the life of the nation. So much had happened so quickly. The mass killings of some 1.5 million of their people; the Treaty of Sevres, which was beneficial for Armenia, was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne that favored the perpetrators of the genocide; and the first free and independent Armenian Republic was quickly subverted by the Bolsheviks who had seized power in Russia. It was through the pages of the Hairenik that some sense could be made of their world that was being rapidly reshaped.

The Hairenik connected them to other Armenians, if not actually, then symbolically. It was a good feeling. It helped assuage the emotional and psychological burden carried by the survivors as they adapted to a new country and the task of rebuilding their lives. The Hairenik was one of the few tangible links many of the survivors had that not only connected them to their roots, but reinforced their determination to succeed. Given its wide readership, the Hairenik was a valuable medium for survivors seeking information about their loved ones.

During this celebratory year during which we recognize the 120th anniversary of the Hairenik and the 85th anniversary of its English-language sister publication The Armenian Weekly, we should remind ourselves that a newspaper is nothing more than paper and ink. What makes a newspaper vital and its longevity noteworthy are the editors, men and women, who give life and credibility to its printed pages. Both the Hairenik and the Armenian Weekly have been fortunate to have had a succession of men and women appointed as editors who were dedicated and intellectually equipped for the task.

Two editors of the Hairenik need to be mentioned, not because they overshadow the others, but because of the unique circumstances associated with their tenure as editors.

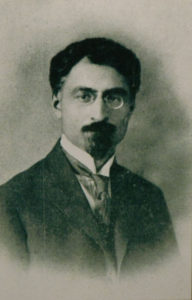

Atom Yardjanian (well known by his pen name Siamanto) was at the helm of the Hairenik for only a short period of time (1909 to 1911). He was sent to the U.S. by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) to serve as editor of the Hairenik. He was a young man who had achieved prominence as a poet. It was unfortunate that he decided to return to Constantinople in 1911. He was among the first of the Armenian intellectuals from that city to be surreptitiously rounded up by the Ottoman Turkish authorities to be tortured and then murdered. His death and that of other Armenian intellectuals was the prelude to the mass killings and deportations that took the lives of some 1.5 million Armenians. His untimely death at the age of 37 was a tragic loss for the nation. His appointment typifies the caliber of men that were called upon to serve as editors.

Artashes Chilingirian (better known as Ruben Darbinian, a name taken years earlier in Germany to hide his true identity from authorities) has the distinction of being the longest serving editor of the Hairenik (1922 to 1968). Mr. Darbinian had served in the government of the first free and independent Armenian Republic and had considerable experience as editor of various ARF publications before assuming the position at the Hairenik.

His tenure witnessed the maturation of the Diaspora. It was during the post-World War II years that Armenians came into their own. No longer “survivors” they had successfully adapted to their new environment and, with their children, were active contributors to their adopted country. The demographic composition was also changing as their children were slowly becoming the majority.

It was under his watch that a column in English was included in the Armenian language Hairenik. It was so well received by readers that what began as an experiment in 1932 became a full-fledged English language publication in 1934 to join the Hairenik as a sister publication. James Mandalian was appointed as the first editor of the new publication whose masthead read, Hairenik Weekly. In 1969, its name was changed to the Armenian Weekly.

The Weekly was an instant success. Its readers were drawn from an ever expanding pool of Armenians who were more comfortable with English than Armenian. It was the language learned in school and constantly heard outside the home. The content of the Weekly was eclectic. It included original works by Armenian writers, political analyses of events relevant to the takeover of the first free and independent Armenian Republic by the Bolsheviks and the post-genocide period. Later it contained articles reflecting the ARF’s position with respect to Turkey and communist Russia. Local news was also an important component, especially the activities of the youth.

It should be noted that the Hairenik and the Armenian Weekly are “not-for-profit” publications of the ARF. These publications were significant factors in the acclimatization of the survivors to their new environment. The ARF was a respected entity. Its activist agenda in Anatolia and the Caucasus not only was known to the survivors, but the position of the ARF on major issues resonated with many of the survivors. The party was a proponent of Armenian nationalism and ideologically supported a greater Armenia (that included Wilsonian Armenia). Its socio-economic philosophy was egalitarian. As Armenian nationalists they were avowed anti-communists. And, in the aftermath of the genocide and the favorable treatment of Turkey by England and France (Treaty of Lausanne) at the expense of Armenians and Armenia, the ARF became the principal adversary on the world stage of the Turkish government’s policy of denial and historical revisionism with respect to the genocide and its consequences. It is not hyperbole to say that reading the pages of the Hairenik or the Weekly was reassuring and even inspiring at a time when the past was too painful to remember and the future was in doubt.

In 1991 when the second free and independent Armenian Republic was declared, the Hairenik and the Armenian Weekly were seasoned publications. They fulfilled a vital role in introducing Armenia to a diasporan population that knew little about the country of their heritage. Quite frankly, there had been little interest in knowing about a country that had been under Russian communist control for some 70 years. During much of this time the world was in the throes of the Cold War when Russia was considered a threat to the countries of the free world.

Once again, the Hairenik (now with its sister publication, the Armenian Weekly) filled the breech. They introduced generations born in the Diaspora to their motherland as well as being instrumental in nurturing an interest in Armenian affairs. Readers were kept informed through reports, analyses and commentary that encompassed all relevant aspects of life in the newly established second free and independent Armenian Republic.

A few years later, in 1994, a ceasefire ended a war waged by Azerbaijan against the Armenians of Nagorno Karabakh (Artsakh) who had voted unanimously to declare their independence. Diasporans knew very little about the new state, its creation or its geopolitical importance. Again, it was the Hairenik and The Armenian Weekly that ably and reliably introduced their readers to the land and people of Artsakh.

The Armenian Weekly has become an important source of information concerning all aspects of the Armenian homeland. It is also a very important venue for the exchange of ideas concerning contemporary issues facing Diasporan communities, Armenia and the newly created de facto state of Artsakh. The editors are committed to publishing positions that are thought provoking and do not necessarily support accepted orthodoxy. It has become a valuable medium for budding journalists, seasoned writers and academicians to express themselves on issues and problems confronting Armenia and the diasporan communities.

The introduction of an online edition has given the Armenian Weekly a worldwide readership. The newly launched podcast pilot, which will soon hopefully blossom into a weekly program, can provide a platform for relevant content for the new generation. The published commentary offered in response to articles indicates a readership that is knowledgeable, conversant with contemporary issues and acutely concerned with conditions in Armenia and Artsakh. It is also a testament to the loyal following that the Armenian Weekly has developed and become a place of real participation.

Both the Hairenik and The Armenian Weekly have become vital institutions in the Armenian community. Nurturing interest supported by information creates a knowledgeable readership. That noble purpose has become the hallmark of these newspapers. However, we should never forget that this achievement belongs to the succession of exceptional men and women editors appointed by the ARF who labored selflessly for the benefit of our people and a free and independent Armenia.

Be the first to comment