Ever since the previous (84th) Armenian Patriarch of Bolis, Mesrob Mutafyan died on March 8, 2019, conspiracy, gossip, intrigue, natural/normal competition, speculation and Turkish government interference with and intrusion upon the process of electing a new Patriarch have been pervasive.

I have no great love for religious institutions. But the Armenian Apostolic Church is OURS, and if someone is disrupting its processes, generally messing with it, or usurping its independence, then I feel compelled to chime in. In this case, since the actual election process is starting December 7th after much gamesmanship, I think a very condensed chronology of what’s been going on would be helpful to readers (and me), particularly since much more about this issue has appeared in Armenian than English in our communities’ publications.

After Mutafyan’s karasoonk, June 27 was set as the date to elect a locum tenens (interim Patriarch) whose main duty would be organizing the election of a permanent Patriarch. On the eve, literally, of the election, a decision by Turkey’s Interior Ministry passed through the Bolis Prefecture postponing the election by one week was conveyed to the Armenian community through Archbishop Aram Ateshian (who is also one of the candidates for the permanent position and has something of a reputation for cooperating a bit too much with the Turkish authorities). Of course this set off a round of social media chatter that he had arranged for the delay because he feared not be elected. But Bishop Sahag Mashalian (another candidate for the permanent position) confirmed Ateshian’s story.

Garo Paylan, an Armenian Deputy in Turkey’s parliament quickly directed some very pointed questions at Interior Minister Suleiman Soylou. Meanwhile, Mashalian spoke out against Ateshian asserting that the latter had sent a secret letter to the ministry which triggered the delay and Ateshian responded that Mashalian was always seeking “interferences” (i.e. empty conspiracy-mongering).

Ultimately, Mashalian was elected Locum Tenens by a 13-11-1 vote on July 4, the postponed date. The following day, Ateshian was elected chair of the religious council. On July 11, Turkey’s Constitutional Court published its earlier ruling that the government of Turkey’s interference in the internal affairs of a religious institution violated freedom of religion and was unconstitutional. Later, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom would condemn the Turkish government’s interference in a religious community’s internal election.

An electoral commission was established to prepare the new Patriarch’s election. At its regular meeting of July 29th, a timetable was unanimously adopted targeting December 7 for the election of the clerical delegates, December 8 for the election of the lay delegates, and December 11 for the election of the new patriarch by the delegates. On July 31, this schedule and a request for bylaws to govern the election were sent to the Turkish government through the Bolis prefecture in a letter signed by the commission’s chair, Khosrov Keoletavitoghlou, and Mashalian, as Locum Tenens, following the established rules. The timetable was also sent to the Interior Ministry for approval. But there was no progress by the Locum Tenens in inviting potential candidates.

On September 23, the Interior Ministry sent, through the Bolis governorate, bylaws governing the patriarchal elections. The document is lengthy, but the key provisions are found in Item 25, thus:

1- A candidate’s father must have been a citizen of Turkey

2- A candidate must have the Turkish government’s trust/confidence

3- A candidate must be in the employ of the Bolis Patriarchate

4- A candidate must be at least 35 years old

5- There must be no court judgments against a candidate

6- A candidate must be ready to accept patriarchal responsibilities in a timely manner

The third point set off a firestorm since it was new. The 1961, 1990 and 1998 patriarchal elections had been governed by the other five points only.

The new restriction reduced the pool of potential candidates to only three, excluding at least ten others. Remember that the Bolis seminary had closed down many years ago, and no new clergy has been trained there. Also, three patriarchs – Khachadourian, Kalousdian and Kazanjian – who served during the life of the Republic of Turkey had come from outside. This led to another protest by Paylan, who pointed out, among other issues, that the new rule runs afoul of the finding of Turkey’s constitutional court because it is contrary to the traditions of the Armenian community, church and patriarchate. With this constraint in place, a democratic and fair election is precluded and potentially qualified candidates are excluded.

As a result, the organizing committee, at its September 30th meeting decided to proceed with further steps in the election only after consulting with all the leaders of Armenian community institutions. A meeting with those leaders was called for October 3. Meanwhile, a group named “Pubic Initiative” was demanding that the authorities protest and pursue the amending of Item 25, reminding the Armenian community of its hard-won right to choose its patriarch according to its own rules and traditions.

At the October 3rd meeting, the clerical council’s report was heard first. The clergy supported going forward under the government’s rules without protest. Then, each community institution’s representative was heard – 18 were for proceeding and 12 wanted to object. The electoral commission’s vote was split 8-8. But in light of the positions taken by the institutions and clergy, the decision was made to proceed with the election as scheduled. This led some members to resign in protest.

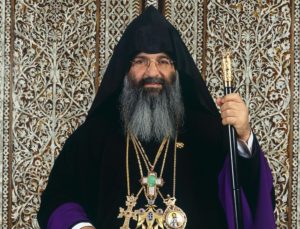

In an October 20th letter, Archbishop Karekin Bekjian, the third eligible candidate under the new rule along with Ateshian and Mashalian, withdrew. He cited the danger the new rule posed for the future of the Patriarchate and called on the other two to also withdraw their candidacies. Bekjian had served as Prelate in Germany, and was elected Locum Tenens in 2017, but was prevented from taking office by the Turkish government and later went back to Germany. The Prelate of the Diocese of Coocark/Googark (in the Republic of Armenia), Archbishop Sebouh Chouljian, followed suit and withdrew his name. Like Bekjian, he called for the withdrawal of the others, too. He contended that the election would lack legitimacy and urged Ateshian and Mashalian to stand up for their brothers of the cloth and community.

On November 5th, the Public Initiative group filed suit to stop the election. They argued that since everyone agrees the new rule is bad, but no one acts accordingly, their requests to formally protest and ask for revision of the rule have gone unheeded, and proceeding with the election sacrifices the future to salvage the present, they were forced to go to court.

“Nor Zartonk” also jumped into the fray. You will recall it was the driving force that helped save “Camp Armen” and restore it to its rightful owner a few years ago. Not only is Nor Zartonk supporting the lawsuit, but it is also calling for all Armenians to boycott the election (they would otherwise be electing delegates who would subsequently vote to elect the patriarch). On top of this, Chouljian confirmed that during a meeting in Echmiadzeen, Mashalian had asked him to call on his supporters not to boycott the election. Chouljian turned down the request.

On November 9, Dicran Gulmezgul, chair of the board of trustees of the Carageozian Home had a 90-minute meeting with Interior Minister Suleiman Soylou (quite lengthy for that level of government). The latter wanted the election to proceed as authorized by the government since he claimed the rules were drafted in consultation with (unnamed) members of the Armenian community. He proposed establishing a permanent set of election bylaws (that would please all parties) subsequently, so that this kind of situation could be avoided when the time came to again choose a new Patriarch.

On December 4, a court dismissed a suit filed by Simon Chekem, board of trustees member of the Three Altars church of Bolis’ Beyoghlou neighborhood. The court found that he should have sued the Electoral Commission, not the government. It’s not clear to me if this is the same suit as the one referenced above.

So it appears the election will proceed, barring any last minute legal surprises and on December 11, the 85th Patriarch of Bolis will be elected. The two choices are known to be far too accommodating of the Turkish government. This turns off many potential voters, along with the injustice imposed by the new rules that excludes qualified candidates for the first time, going against the church’s traditions. Turnout may be quite low for these reasons coupled with the calls to boycott. It seems the church member lists, i.e. voter rolls, are not updated and the electoral commission has been evasive about them, simply claiming that approximately 60,000 people are on those lists. Half the electoral commission ultimately resigned. All of these factors will make for a patriarch whose legitimacy is questionable. He will therefore be far more reliant on the Turkish government for authority, thus making him far more pliant and less likely to serve the Armenian community’s interests.

Under the circumstances, my choice would be to boycott the election. If you have any friends, relatives, in-laws or acquaintances who live in Turkey, encourage them to boycott the delegate elections slated for this Sunday (that is if you read this in time). The only argument for voting and electing a patriarch now and under these circumstances is that the seat has effectively been vacant for 13 years, allowing for much mischief and unresolved community issues and needs in the absence of a definitive leader. Nevertheless, a boycott is the better option because accepting this level of disruptive intrusion by the Turkish government in our affairs sets a horrible precedent for the future.

Boycott, if you’re an eligible patriarchal election voter, and encourage others to do the same whether or not you are one.

Be the first to comment