Special for the Armenian Weekly

The first time I came across photojournalist Scout Tufankjian’s work was about six years ago; it was during one of my aimless bookstore strolls that the Armenian last name caught my eye. The name was printed on the cover of a book with a picture of then-newly elected U.S. president Barack Obama shaking supporters’ hands with the words “Yes We Can” plastered on top in big, block letters. I must say, I was quite proud to see an Armenian photographer covering one of the most memorable U.S. presidential campaigns in recent years. Through her book, Scout had presented a behind-the-scenes look at one of the most talked-about moments of the time, a perspective that the public was rarely given a chance to see.

I began following Scout’s work closely in the coming years. From her travels to Eastern Anatolia and Haiti, to her coverage of the revolution in Egypt in 2011 and 2012, her work captured the truest human emotions in a variety of settings and situations.

Born in Boston to an Armenian-American father and Irish-American mother, Scout’s paternal ancestors hail from Musa Dagh, the mountainous region on the Mediterranean coast known for its people’s heroism during the Armenian Genocide. I immediately felt a strong connection to Scout, since my father’s family also came from the same region of Cilician Armenia.

But it wasn’t until earlier this year that Scout and I had the chance to meet and connect on a personal level. She had come to Toronto to photograph the Armenian community as part of her Armenian Diaspora Project, a project that would lead her to Europe, Lebanon, and as far as India to document diasporan communities. Coming off a hectic leg of her journey, which included visits to Armenia, Hong Kong, and France, Scout only had a few days in Toronto, but she managed to catch everything she could. Her demanding schedule and lack of time didn’t deter her from getting the job done and even squeezing in a quick visit in to Montreal to visit the community there.

Scout is truly a renaissance woman. She is doing what so many of us have only dreamt about: traveling to every corner of the world and visiting Armenian communities along the way. I recently had a chance to interview Scout to learn more about her upcoming book, which will present her years of work documenting the Armenian Diaspora.

***

Rupen Janbazian: For the past four years, you have been documenting Armenian communities around the world as part of the Armenian Diaspora Project. When and how was this project conceived?

Scout Tufankjian: Well, I started working on the project seriously about four years ago, in the wake of two years spent covering Obama’s first campaign, but it was really conceived years ago. When I was a kid, I would often spend weekends with my grandparents, who—for reasons I never figured out—would spend the day house hunting. They never moved or anything like that, but in between looking at houses (and a stop off at the zoo to keep me entertained) we would visit their friends for a cup of tea or soorj. As the grown-ups talked, I would pour over the Armenian magazines and newspapers their friends kept on the coffee table.

I grew up in Whitman and Scituate, which was a little outside of the main community in Watertown and Arlington, so I never went to Armenian school or the clubs. We’d make trips into Watertown to buy braided cheese and lahmajun and to go to the church bazaars, but my main access to the greater Armenian world outside of my family and our friends was through these magazines and newspapers. I would see pictures of AGBU school kids in Aleppo or the Homenetmen agoump in Buenos Aires and wonder about them. What did I have in common with these other kids? What was it like being Armenian in Kolkata or Addis Ababa? What were these communities like? Pre-internet, the only way to really find out the answers to these questions was to go to the library. But as you can probably guess, all I could find there were books about the genocide. Now, obviously genocide narratives are important, but that wasn’t what I was looking for. I was looking for who we are now; where we are; what our lives are like; how 100 years of diaspora has affected us. And I kept waiting for someone to write that book. It sounds a little ridiculous, but eventually, I just got tired of waiting and decided to do it myself.

R.J.: You have visited and documented Armenian communities around the world—from Europe to India. What have been some of the most memorable moments during this journey?

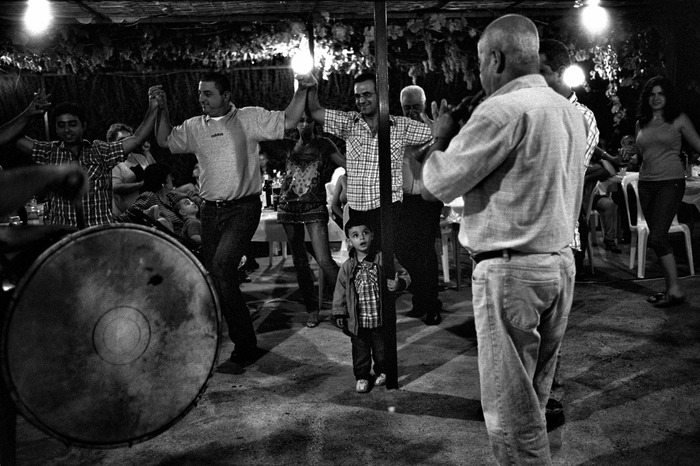

S.T.: Too many to mention: eating manti and laughing with the Atamian/Honsorian family in Kessab; watching the 2010 World Cup in Damascus; dancing to dhol zurna in Anjar; drinking tea with migrant workers in Moscow; attending Easter mass at Sourp Giragos in Diyarbakir; celebrating Vartivar with Istanbul Armenians on Kinaliada the morning after a concert by the Armenian/Turkish/French band “Medz Bazar”; making paper flowers at a pre-wedding feast in Paris; swimming with Syrian-Armenian refugees in Karabagh; listening to Ethiopian jazz sung by the Ethiopian-Armenian musician Vahe Tilbian; watching kingfishers swoop around the Armenian church in Singapore; seeing Charles Aznavour perform in São Paulo; watching adults try (and fail) to control the irrepressible Kevork in Vakifli; marching in the New York Pride Parade with AGALA the day after New York became a marriage equality state; playing tavla everywhere, from the basement of a police station in what was once Hadjin to the club at Sourp Hagop in Montreal; watching an amazing young Australian dance group practice; sharing perfectly silent meals with the monks of San Lazzaro Island in Venice; cheering on the Armenian college students at a Kolkata rugby match, and so, so many more.

R.J.: Talk about some of the challenges these communities are facing today.

S.T.: It seems to me that this is a particularly important and fragile moment in Armenian history. One hundred years after the genocide, the Ethiopian community is down to a few families. Egyptians worried about post-revolutionary upheavals are immigrating to Los Angeles in droves. In Beirut, the last remaining Armenian refugee camp from the genocide era is being demolished and the families evicted. At the same time, the amazing family that welcomed me into their home in Kessab has been driven from it by the advance of the brutal Syrian Civil War and tens of thousands of refugees, many of whom I first photographed in pre-war Syria, have fled the formerly strong and vibrant communities of Damascus and Aleppo to Armenia, Lebanon, and parts further afield. Even more secure communities like Brazil, France, and the United States are worried that, as the younger generations lose the language and marry non-Armenians, their physical survival and their success in their new homelands is at the cost of their culture. So it really didn’t seem like there was a single community that didn’t face challenges of one sort or another.

R.J.: The diaspora is often viewed as a monolithic entity. Although the theme of exile and genocide runs through all, each community—and often each family—is also burdened and influenced by the cultures and realities of their adoptive cities. What were some of the differences between the communities that came through in your photographs?

S.T.: Every community has been influenced in one way or another by their adoptive cities, whether it is France’s support for the arts giving rise to a fantastically vibrant community of French-Armenian artists and musicians, or Kolkata’s Armenian rugby players. The fact that the Lebanese-Armenian community is one of the few where Armenian is still the lingua franca is almost certainly connected to the insularity born out of the Lebanese Civil War. LA is a perfect example of this in a way. To outsiders there are “The Armenians”: a monolith. But to us, you have the genocide-era Armenians, the Beirutahai, the Parskahai, the earthquake/war-era Hayastantsis, and the more recent Hayastantsi economic migrants. And while the outsiders aren’t wrong in that we are all Armenians, each of these communities has their own unique spin on Armenian culture and traditions.

R.J.: What do you see as the advantages of telling stories through photographs?

S.T.: I’m definitely not a writer, so the only way I can really tell our story is through photography. But beyond that, there is a universality to images that allows for a greater connection between the subject and the audience. Especially since this is a portrait of a people who live in over 85 different countries and speak umpteen different languages, I wanted it to be able to speak to and for as many people as possible.

R.J.: Between 2006 and 2008, you covered then-Senator Barack Obama’s campaign for president, taking over 12,000 photographs and ultimately releasing a book—titled Yes We Can: Barack Obama’s History-Making Presidential Campaign—that featured a selection of the photographs and made it to The New York Times’ Nonfiction Best-seller List. How was the Armenian Diaspora Project different than covering the campaign? What were some of the challenges you encountered?

S.T.: Well, the great thing about covering a campaign, especially in the later stages, is that everything other than the actual taking of the pictures is handled for you. Once you climb on board the plane or bus, you are basically led around and the only decisions that you have to make involve who, what, where, and when you take the actual images. The campaign staff handles transportation, food, scheduling, access, and anything else you can imagine. With this project, however, all the decisions were mine. Where to go, when to go, what to focus on, who to meet with—all of those decisions were mine. So if I made a wrong call, it was completely my fault, which was a bit terrifying.

But the flip side of that is that this is the most personal project that I have ever worked on (and can ever imagine working on). Covering the two Obama campaigns was an amazing experience that I will always treasure, but this project means so much more to me.

R.J.: The Armenian Diaspora Project was successfully crowd-funded through the Kickstarter platform. Why did you choose the crowdfunding route and what are some of the advantages and disadvantages of this type of fundraising?

S.T.: The project was originally entirely self-funded, using the proceeds from my earlier book. Once those funds ran out, I would save up and go on trips as I could afford to. And I could have continued on that route for the next 30 or so years and eventually have a book ready to go by 2035, or something like that. Maybe. But I really wanted to have something finished by the Centennial of the Genocide, so that we could celebrate our survival and accomplishments at the same time that we were mourning our losses. So after a lot of consideration, I decided to try crowdfunding. Frankly, it was a scary thing to do. I’d been working on this project on my own for so long, that I was really worried that I was the only person it would mean anything to. Maybe I was doing it wrong. Maybe no one would care. So for me, seeing the success of the crowdfunding campaign and how the project resonated for other people was so unbelievably moving. I love how crowdfunding allows other people to really be a part of it and turn it into something that the entire community has some ownership over.

R.J.: In August 2012, you took a photo of Michelle Obama and President Barack Obama hugging each other, and the Obama campaign staff sent this picture out on the official Obama Facebook and Twitter accounts the night of the election, Nov. 6, 2012. This picture became the most liked photo on Facebook and most retweeted Tweet in history. Can you comment on the power of social media and how it has helped you as a photographer?

S.T.: I never could have done this project without social media. Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration, but it would have been very different. I first started this project before social media became as popular as it is now, and the main way I got in touch with people in the communities was through the organizations. The organizations continued to be a huge and important resource for me, but as you know, there are loads of Armenians who aren’t involved in organizations, and I wanted this project to represent them as well. And I can’t overstate how helpful Facebook was in getting in touch with these people, especially in the last year of the project, once I had set up a Facebook page for it and word had begun to spread.

R.J.: The book’s release date was originally slated for April 2015, the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide. Can we still expect to see the book by then?

S.T.: Yes! If we stay on schedule, it should be out by March 30 (fingers crossed!) and will be titled, There is Only the Earth: Images from The Armenian Diaspora Project. I hope to have the Amazon listing up soon, as well as a dedicated website for the project, but until then, people can get in touch with me at armeniandiasporaproject@gmail.com and I can put them on a mailing list to keep them up to date on the book release!

Obama lied when he said he would acknowledge the Armenian genocide as president, and so did our alleged “friend” Samantha Power (now UN ambassador) who has had nothing to say about our genocide since she was appointed by Obama 6 years ago.

Will we and Scout ever learn?

We have another prominent Armenian photographer in the Detroit, MI area. Her name is Michelle Andonian. She, too, has traveled extensively and is also doing a centennial project.

What a great article! The writer asked questions that elicited interesting responses from Scout. Looking forward to her upcoming book.

Dear Vahe. Why to immerse into political dialogue of Obama or Power or ….. Enjoy the photographer, encourage the project, commend her devotion, and constructively add to it through pinpointing betterment, while remaining apolitical. Thank you.

I am so thrilled Scout has taken on this important project. PROJECT SAVE of Watertown,MA. saves the

archival photos, and Scout documents the current community. What wonderful ways to preserve the

history of the Armenian people.

You have brought a new blueprint to the ongoing history of Armenan people throughout the world…I look forward to reading your book.

Thankyou Scout for your inspiring work…you have given Armenians around the world a heightened awareness of our history. I look forward to reading your book.