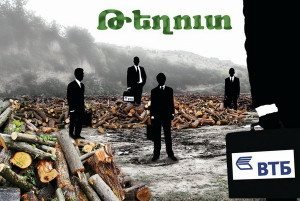

The Teghut Defense Group (TDG), an environmental protection organization, fights against threats to Armenia’s natural treasures. As their name suggests, their primary focus is protecting the lush Teghut Forest located in the Lori region. The group opposes a mining project by the Armenian Copper Program (ACP), which has already received approval from Armenia’s Nature Protection Ministry and will clear-cut 1,500 acres of the forest to extract copper and molybdenum.

Activists are concerned about the effects of mining on the region. They say mining waste will be dumped in the nearby Duqanadzor River Gorge, contaminating the area’s water supply and leading to birth defects. The group cites the Alaverdi case as a comparable example: Prior to the ACP’s operations in the area, no birth defects had been reported in Alaverdi; by 2009, after nine years of factory activities, 28 cases of birth defects were reported. The number had risen to 107 three years later.

The group is also outspoken about another iron mining project near the Datev Monastery, in the village of Svarants. In April, Hetq editor Edik Baghdasaryan wrote an op-ed titled “Who can Save Tatev from Greedy Mining Interests?” Baghdasaryan pointed the finger at two National Assembly MP’s, Vardan Ayvazyan (who had once served as minister of nature protection) and Tigran Arzakantsyan, who were responsible for selling three mines in Armenia to Fortune Oil, a Chinese company. One of the mines was the Svarants mine; the other two are located in Hrazdan and Abovyan. According to Baghdasaryan, Ayvazyan’s son and Arzakantsyan are the owners of Spice Steel, the company holding the exploratory license for Svarants.

“All government structures in Armenia have just one thing on their mind—how to embezzle state funds,” Baghdasaryan wrote. “Officials working in these state institutions are only interested in one thing—how to advance their private businesses through the abuse of their office.”

Environmentalists pursued the Teghut issue in court. Three organizations—Transparency International Anti-Corruption Center, Ecoera (Ecodar, in Armenian), and the Helsinki Citizens Assembly Office in Vanadzor—filed a suit with the Administrative Court of the Republic of Armenia. The case was rejected twice, after which Ecoera and Transparency International filed a claim with the Court of Cassation.

“Only one of the applicants, Ecoera, was allowed legal standing because it had environmental protection mentioned directly in its statute,” Arpine Galfayan, a member of TDG who has been following the case, told the Armenian Weekly. “The local courts took the complaint back and forth in the Administrative and Cassation Courts, but in the end all the levels of courts denied the right of NGOs to pursue public rights, so the verdict very much sounded like ‘We are not going to examine the case because you don’t have the legal standing, the Constitution does not allow you that.’”

However, according to Galfayan, an earlier case resulted in a Constitutional Court ruling that NGOs can legally pursue public rights. “So at this stage, the next step…is to apply to the Constitutional Court about the decisions of the Administrative and Cassation Courts, and to demand another comment on or interpretation of the Constitution regarding NGOs’ rights to protect the rights of other people,” Galfayan said, adding that applying to the European Court of Human Rights may also be an option.

TDG took yet another route by applying to the UN Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee, to which Armenia is a signatory. The Convention grants the public access to information, to justice in environmental issues, and calls for public participation in decision-making processes. “Last year the committee supported our cause and made a harsh statement to the Armenian government about failing to respect the convention in terms of public participation in decision-making in the Teghut issue,” noted Galfayan. Following the rulings by the courts, TDG is applying to the committee once more, this time to draw attention to their exclusion from the decision-making process, with the hope that international pressure sways the authorities to change course.

[monoslideshow id=37]

The issue is complicated, Glafyan said, as big financial interests are involved. “I do not believe the ministry or the government in general are willing to make any radical positive changes.”

The activist is also concerned about the ramifications of the court ruling on Teghut. The court’s decision can now serve as a legal precedent to other similar cases. “A few months ago, an NGO was refused legal standing to sue the government for a mining issue in Kapan, in the south of Armenia,” said Galfayan.

***

Activist Mariam Sukhudyan, along with fellow members of TDG, is in a continuous struggle to raise awareness of the dangers facing Armenia’s environment. Among the individuals whose support they have sought is Serj Tankian, the Grammy Award-winning singer and songwriter. The group approached him during his most recent visit to Yerevan.

Below are Mariam Sukhudyan’s reflections on the occasion of a recent TDG meeting with Tankian.

A few days ago, we wrote a letter to Serj Tankian. We were not surprised when he responded immediately. Many intellectuals, artists, and members of government ignore our letters, and our communication efforts dissipate into nothingness, and forever remain unanswered.

I avoid calling Serj an idol, a symbol, or any other reference that will distance him from us, because he is one of us, a very accessible and warm person. There is something very intimate about him. We didn’t try to get photographed with him, or get his autograph, but, as equals, discussed Armenia’s current stifling reality, trying to find solutions together.

We talked about Teghut Forest, about involving a third party to assess the effects of mining, because, let me remind you, the only report on the advantages and dangers of mining was conducted by the very company involved in the Teghut mining project.

The company itself wrote a report on the effects of mining on the region. You get the idea, right? It was a cynical step, a piece of document that did not correspond to reality.

Three years ago, the Teghut Defense Group met with Armenia’s prime minister to explore the possibility of getting a third-party assessment. He agreed to our proposition. However, as soon as the group found a Norwegian organization ready to take on the task of evaluating the effects of mining, the prime minister forgot his promise and ignored us.

Serj Tankian became quite enthusiastic when he learned that this environmental struggle already has a five-year history, that it has reached the point where TDG will submit a complaint against the government’s decision in court. But since the judicial system is as corrupt, there is no hope of winning the case in Armenia. We are now thinking about going beyond our borders; why not apply to the European Court?

We presented evidence that Armenia (Hayastan) is turning into Arminea (Hankastan) to the Administrative Court. We said that as far as birth defects were concerned, Armenia was second worse among the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), after Kyrgyzstan where there are uranium mines. That is based on 2005 statistics. As time progresses and mining continues, those high numbers point to an extremely dangerous trend in public health.

Let’s now talk about the open-pit iron mine neighboring Datev Monastery. On the one hand we are yelling from the rooftops that we are the first Christian nation; we call it Biblical Armenia, and Noah’s Ark—we say—landed here. On the other hand, we open deadly iron mines next to our historic monasteries. And why are our religious leaders silent? Perhaps they believe that thinking about what is best for Armenia is an anti-government stance?

Our group also discussed with Serj the possibility of organizing an international environmental rock festival in the affected regions, at the mining sites. We’ll divulge the details at a later date.

It was a frank and open discussion. Serj repeatedly welcomed our dedication to the cause. He expressed his readiness to help in whatever way he can. We hugged, and parted ways with renewed spirits, to continue our struggle.

We call upon the Armenian Diaspora to join us in this struggle for our nation’s existence.

Our children’s future depends on us.

–Mariam Sukhudyan

For more information on Teghut, click here.

I do not have much knowledge of which organizations are participating in this dilemma, but I was thinking about UNESCO. I keep hearing about their World Heritage Sites which they protect comprising of both natural and cultural sites. Maybe if not already done so, the activists fighting for Teghut and other historical and natural sites in Armenia could apply for their help.

i know it may have painful effects for real. i do not like the birth defects.

but we have to have some kind of economy—heavy industry. we have to regain our hard work ethic…..the birth defects and contamination of the enviroment should be dealt with head-on.

You can still have/develop a healthy economy without destroying the surrounding environment. Follow the leads of many other Earth-first green projects all over the world to see how mining, forestry and other industries can still occur without damaging the ecosystem. There are areas in the world where open pit mines once stood, but have been filled in with replanted vegetation to where you couldn’t tell there ever was an open pit mine there.

A satirical take (in Armenian) on the Mining Industry in Armenia here: http://www.comedynow.org/2012/01/blog-post.html