High along the grassy mountain slopes above the resort town of Jermuk, completely out of sight from day tourists longing for a cup of warm source mineral water, shepherds tend to their flocks of sheep virtually incognito.

Valodya Gharibyan is a tall, lanky man with a familiar hooked nose that is characteristic of so many Armenian men, on top of which is perched rectangular-framed eyeglasses. His face is beet red, burned by continuous exposure to the harsh sun.

He keeps 600 sheep, 50 of which belong to friends or acquaintances who have entrusted him to care for their animals. Several hired hands are employed to help tend to the sheep and maintain the camp.

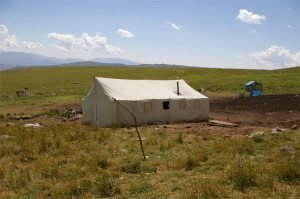

Home is a large canvas tent, under which can be found a table and benches for eating, sleeping mats, a gas stove for cooking, a wood-burning stove, and even a hot water tank. Only 50 meters away is a natural spring from which a constant stream of crisp, pristine water flows.

“This is my area, I’ve been coming up here for several years,” Valodya said. “We used to be based about 100 meters below, but we decided to move up here since it was better for grazing.”

His secluded camp is located about eight kilometers north of Jermuk. The only way to travel there is by sports utility vehicle along a rough-going dirt road blanked with large rocks, intersected by three different mountain spring brooks and in some places, blocked by pools of oozing, gummy mud.

Valodya has four donkeys, one of them only a few months old, that are used mainly for transporting goods and supplies. At least two horses are available at all times for nimble transportation. On constant guard are six Gampers—purebred, extra-large meaty dogs with long snouts and thick, wiry hair that have been indigenous to Armenia for countless centuries.

The Gamper, which has a loving temperament akin to that of a Labrador Retriever, is a close companion to people. Yet the dogs are fearless protectors of the camp. Shepherds prize Gampers for their prowess in challenging wolves that creep under complete darkness in starved anticipation of capturing sheep. For this reason, their ears and tails are cropped short when they are still young to sway clashes in their favor. A wolf could otherwise easily inflict injury on a Gamper by tearing the ear with its sharp teeth.

There are two bins in which the animals are temporarily kept when they are to be milked. From the sheep’s milk delicious cheeses are made and sold on the market. One kilogram sells for 1,000 dram (approximately $2.70).

A single sheep can potentially yield 10 kilograms of milk during a three-month milking period. In all, four metric tons of cheese is produced for the year from Valodya’s flock.

He also makes business by selling wool at a cost of 2,000 dram per kilogram. The wool shaved from a single sheep is about 1.5 kilograms in weight.

The money earned from the cheese and wool sales is primarily used for various operational expenses, such as healthcare for the sheep and shelter in the winter months.

But the real profit comes from the lambs, which are sold when they are mature in the spring. Each year the oldest sheep are picked from the flock and sold as mutton. The flock is replenished with fresh lambs that are kept into the fold.

Valodya distinguishes his sheep from those in neighboring herds with painted green markings on their backs.

“I also give names to at least 30 percent of my sheep and identify them by their facial features or physical traits,” he said. “Every one has something unique about it. There’s one sheep now that has leg pain we call topal [lame] for instance.”

The female sheep are separated from the males until mating season, which will begin in about one month.

In mid to late September, the sheep will be herded and headed home to Aigavan in the Ararat Valley over a particular route that the herders follow along the mountainsides of Vayots Dzor. They will make their five-day trek across the northern slopes of Vayk and Yegheknadzor, then on to points west, until they finally cross over the mountain range separating Vayots Dzor from Ararat.

The sheep will be kept in a shed that Valodya rents, large enough to accommodate all 600 of them. They stay warm by their own body temperatures while huddling.

During the winter, Valodya and his helpers will take turns tending to the sheep and supervising the birthing of the animals in two-week shifts, while taking time off during the other weeks.

He has four neighboring shepherds, virtually all of whom are also from the Ararat Valley. Two of them are Yezidi Kurds. The woman who tends to the washing, cooking, and cleaning chores on his camp, named Datevik, is also Yezidi.

One of the other herders, named Armen, described some of the problems that are expected while making the journey to the Jermuk region with his flock of sheep.

“When I travel though a particular area my path can be blocked by a village head or his son, who claims that the territory we are crossing is now their own, and they try to extort bribes so we can continue,” Armen said.

“But I have an official document ensuring my safe passage across specific territories. If you know the law, they can’t do anything.”

Valodya, 31, cannot imagine doing any other kind of work. “I have been tending sheep for 10 years,” he said. He dreams of being able to increase his flock, which he admits can be problematic because of the additional, reliable manpower required.

“Someday I hope I will be able to manage 1,000 sheep or more,” he said. “It’s a difficult job, but I love what I do. I love to be here.”

Be the first to comment