Artsakh remains

Where those displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh are resisting cultural and political erasure

This report was prepared independently by the University Network for Human Rights. Contributions by UNHR student researchers Noah Haas, Inaya Raja and Lyanne Wang. Interpretation by Ani Barseghyan. Photos by Lyanne Wang and Emily Wilder. Illustrations by Inaya Raja. The authors of this piece are not affiliated with any Armenian political party.

Emily Wilder is an independent journalist and researcher with the University Network for Human Rights, which investigates abuses worldwide in partnership with frontline communities. Since 2022, UNHR has conducted field research in Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia and comprehensively documented human rights violations ahead of and during the 2023 ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenians. This report arises from UNHR’s June 2025 fact-finding on the challenges facing the displaced community and efforts to preserve its identity and culture, with most of the reporting predating August 2025.

On a quiet artery connecting busy Hrachya Kochar Street to busier Komitas Avenue in north Yerevan, a two-story yellow building blends into the surrounding apartments and shops. Sometimes, a rack of towels placed at the stoop announces that a salon is open for business on the second floor. Other times, people find its door only through word of mouth.

Despite the nondescript exterior and lack of signage, Sargsyan Beauty bustles with clientele. Women gather from near and far—including from Gyumri, over 100 kilometers away. Many come to experience what an afternoon felt like in Nagorno-Karabakh, or Artsakh—the ethnically Armenian enclave within Azerbaijan’s borders that was emptied of nearly all its denizens following an Azerbaijani drone offensive in September 2023. The salon, owned and fully staffed by displaced women, offers a space to meet friends old and new and reminisce in their unique dialect of Armenian over coffee, paklava and zhengalov hatz (a traditional regional flatbread)—creating a rare sense of home for women who lost theirs.

“There are moments we forget we are not in Artsakh,” owner Inga Sargsyan told the University Network for Human Rights (UNHR).

Since Nagorno-Karabakh’s rapid dissolution, the once 1,400-square-kilometer republic was brought in pieces by its refugees over the border and scattered across Armenia. Two years later, what remains of Nagorno-Karabakh now lives where its former residents, called Artsakhtsis, gather: behind the unassuming, unmarked door of Sargsyan Beauty; a few conjoined rooms nestled below a busy Yerevan boulevard where displaced children and adults learn traditional regional crafts; Facebook groups of once-neighbors crowdsourcing tips on adjusting to their new lives in Armenia; and the former unofficial embassy of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic in Yerevan, which has served as the refuge of the remaining representatives of the Artsakh government, a community center, television station and main political representation for those fighting for return.

In July 2025, the Armenian government filed a lawsuit seeking to reclaim the building, with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan telling reporters that the property “should belong to . . . Armenia” and that he “cannot allow a second state to exist within the Republic of Armenia,” according to ArmenPress. Artsakh officials condemned the action, saying it threatens the preservation of their community’s identity and rights.

The legal challenge underscores that these physical spaces are more than remnants of what people have lost. Leaders and experts told UNHR that their existence is vital not only for the community to thrive self-sufficiently amid severe social and economic challenges, but also to keep Artsakhtsis’ culture, dialect, history, hope for return and struggle for rights alive.

“When we create infrastructures, it does support future efforts towards the right to return,” said Apres Margaryan, director of the Center for the Preservation of Artsakh Culture, which coordinates many of Artsakh’s former state cultural institutions, as well as 11 cultural NGOs and 500 artists and representatives. “If we forget our identity, our dialect, our culture, then we would have nothing to return to. But as long as we preserve it here, we will have the hope that we will someday return and preserve it further in our homeland.”

The urgency of preserving such spaces has intensified amid evolving political dynamics in Armenia and the region. In early August 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump hosted Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev and Pashinyan for a publicized meeting to initialize agreements recognizing each other’s “sovereignty, territorial sovereignty, inviolability of international borders and political independence” and granting the United States exclusive development rights over a 32-kilometer corridor through southern Armenia, connecting Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave, to be dubbed the “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity” (TRIPP). A draft agreement circulated after the meeting among the heads of state indicated that Armenia will withdraw its legal claims against Azerbaijan related to alleged abuses leading up to and during the 2023 mass displacement.

Leaders of the displaced community have claimed that the agreement process has excluded the conflict’s primary victims and, if the measures proceed, could undermine Artsakhtsis’ right to return to their homes, even as the initiatives are framed as promoting peace.

“But in reality, it is not a peace process,” said Artak Beglaryan, former human rights ombudsperson for the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh and current president of the Artsakh Union, an NGO advocating for the collective rights for a “safe return and dignified future” of the displaced community, in a June interview with UNHR. Beglaryan and other Armenian and international rights groups argue that negotiations have been predicated on impunity for crimes against and erasure of a people. The agreement would be “at the expense of justice, at the expense of restoration of our rights,” he said.

In an address from parliament after the White House meeting, Pashinyan said continued demands for return of refugees displaced during the conflict are “dangerous” and “undermine the peace established between Armenia and Azerbaijan.” He called on his “compatriots from Karabakh” to “establish themselves here as full citizens of Armenia.”

Pashinyan’s statements challenge diplomatic and legal efforts to secure Artsakhtsis’ rights. A February 2025 report by the Aram Manoukian Institute for Strategic Planning found, based on international media and human rights reporting, that “Azerbaijan’s systematic attacks, forced displacement and destruction of cultural heritage are elements of a premeditated campaign to expel Nagorno-Karabakh of its ethnic Armenians, triggering international legal obligations, including a sustainable right of return.” This conclusion echoed previous calls by Human Rights Watch, the International Association of Genocide Scholars and the Swiss Parliament, which in October 2024 passed a motion to establish an international peace forum enabling dialogue between Azerbaijan and the displaced community “in order to negotiate the safe and collective return of the historically resident Armenian population.”

Artsakhtsis and broader Armenian civil society have sought to amplify the displaced communities’ voices in response to what they claim is the Armenian government’s role in ongoing erasure.

“They do not not want our people to preserve their identity and, as a result, they do not want to preserve our struggle as a separate community for our rights,” said Beglaryan. “That is why they want to fully close the page of Artsakh people’s struggle: as a people, as a whole, as a community.”

Though Artsakhtsis have resurrected pieces of their home after resettlement, interviewees emphasized that piecemeal, grassroots efforts alone are insufficient to resist the forces pushing them to disappear. Leaders have unsuccessfully advocated since the 2023 mass displacement began for Armenia to create dedicated settlements that could reconstitute the close-knit Artsakhtsi communities, which many believe is necessary for continuity of peoplehood in displacement.

With the dispersal of these communities also came the loss of “indigenous knowledge and culture” and “the social cohesion and cultural bond that would have helped them to get through their trauma,” according to Greg Bedian, director of operations for the Tufenkian Foundation, which is piloting a housing program for 20 displaced families in Svarants, a village in the southern province of Syunik.

Without such programs on a mass scale, “practices will be lost, language will be lost,” Bedian added. “Living together, co-habitating,” according to Armine Tigranyan, cultural heritage expert and lecturer at Yerevan State University, will allow the culture to survive. Yet, despite these stakes, such programs are virtually non-existent outside the small Svarants project, said Margaryan, which “makes it difficult to preserve our identities. So, we put all our efforts into doing that ourselves.”

Sargsyan Beauty: A portal to Stepanakert, refuge from discrimination

Only observant passerby might pick up the symphony coming from the second-floor window on a warm Wednesday afternoon in June—the whistling of hair dryers, the motorized hum of electric nail files, a water kettle perpetually reboiling and chatter in both standard Eastern Armenian and the Artsakh dialect.

“People do not just come here for services; they come to relax, to have coffee. It feels like my old salon back in Stepanakert,” Sargsyan said.

All Sargsyan has left of her once-thriving salon in Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital are her hair dryer and scissors, which she wielded as she cut and styled. Behind her, sun poured in through large windows, reflecting off sparkling drapes. Throughout the afternoon, each new arriving customer piled more sweets onto the crowding coffee table. Since launching, Sargsyan’s team has grown to eight, and they quickly “became a family,” she said. Most of the women did not meet until resettling in Yerevan, but all were displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023.

Each of the women recalled the harrowing details of the mass exodus as though only days, not 21 months, had passed. Some lost family members or acquaintances; all lost their homes, family land and burial grounds, access to religious pilgrimage sites and the sights, smells and sounds of home. On the eve of her departure, another stylist named Inga Sargsyan (of no relation) looked around her house, unsure which memories to take with her if she could not return. “How could I decide?” she asked.

The women now live with the wounds of displacement. “Sometimes I lie down, close my eyes and try to remember every little detail of my house, what is in the cupboards. I live in my memory,” said Gayane, the resident electrolysis technician. “It is not the house—just to go back and lie on the soil would be enough.” The pain intensifies when she thinks of her mother’s grave, which she can no longer visit. “I would not wish it on my worst enemy to lose their homes, to lose their cemeteries where their loved ones are buried,” she said.

Working in the salon together offers a small salve. Outside, looming economic and social uncertainties cannot be fixed with a conversation in a childhood dialect, a taste of Artsakhtsi home cooking, a tearful embrace or a laugh over a shared memory. But, owner Sargsyan said, “if we were not here, if we did not have this, we would lose our minds. This place is what keeps us sane.”

As much as they remember the worst events, the women together also celebrate the new milestones—proof of life’s persistence and their own resilience. While a client from Stepanakert named Gayane sat with strips of foil in her hair, waiting for the dye to develop, team members danced in with a lit cake in a surprise celebration of her 63rd birthday. Elated, she said, “I have been coming to this salon for years. I come here to relax, to be happy. It is very special here.” Through joyful tears, Sargsyan said, “This is how it is: we cry, we laugh. We consider ourselves lucky, even though we have lost our homes and everything.”

Clients like Gayane, old and new, brave Yerevan’s traffic to spend the afternoon in this environment. Tatevik Grigoryan, similarly, said Maria has been doing her nails for seven years and recommends her to others she meets now—but it is not just the manicure that brings her back. “It is kind of like a community,” she explained. “We talk about the news, jobs, what people need. To do it alone is very hard.” Siranush Sargsyan, a journalist from Nagorno-Karabakh who now lives in an area of the city some distance from the Komitas neighborhood, said she comes to Sargsyan Beauty even though there is another salon right by her apartment. To her, the salon experience is quintessentially Artsakhtsi—an accessible and regular social activity for women with few other options, especially during the blockade. “Without electricity, water, soap—visiting the salon was so important,” she said.

The salon also provides refuge from anti-Artsakhtsi discrimination, which the women reported as infrequent but deeply hurtful. In fact, an experience of bigotry at a previous place of employment in Yerevan pushed Sargsyan to open her own shop. There, she would speak in her dialect with other Artsakhtsi coworkers, in their gregarious, “very warm” manner, but was admonished by the owner. “He said, ‘this is not a family business; you are trying to take over.’ After that incident, I came home and my son and husband told me I should not go back.”

Reports of discrimination against Artsakhtsis, both official and casual, have grown since September 2023. Prominent members of Artsakhtsi and broader Armenian civil society have raised concerns that high-level political figures have directed “hate speech” against the displaced community and their representatives—including blaming Artsakhtsis for their displacement and telling them they “have no place”—publicly, on television, on social media and in private. In April, Artsakhtsi journalist Tatevik Khachatryan presented a dossier of such alleged discriminatory speech to Armenia’s prosecutor general and called for an end to such “Artsakh-phobic propaganda.”

Preserving an endangered culture at the Hadrut Children and Youth Creative Center

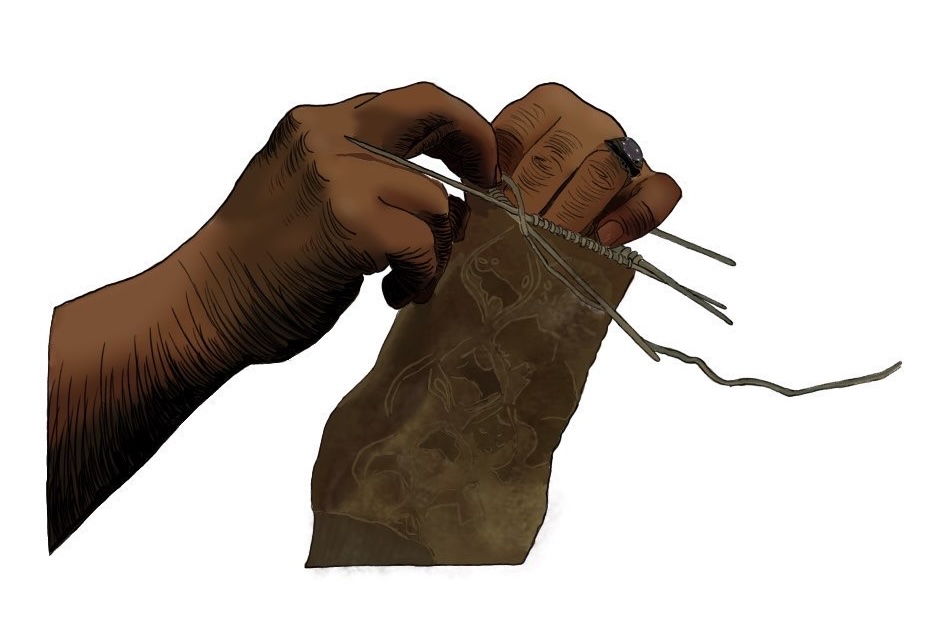

In another tucked-away corner of the city, an eclectic, technicolor exhibit of Artsakhtsi arts and crafts adorns the walls of the Hadrut Children and Youth Creative Center. Filling the space are canvas paintings, felted textiles, stained glass mosaics, wooden sculptures, woven rugs and wooden tables around which two dozen women focused keen eyes and fingers on traditional embroidery and knitting. Founder Ira Tamrazyan roamed about, offering insights and a bowl of ripe, purple cherries. Through a doorway, a computer lab hummed with schoolchildren learning to code, while other children occupy cluttered corners, gossiping in the Artsakh dialect.

“Everything in the center is free,” Tamrazyan said, adding that the programming, which serves both youth and adults, is the only of its kind in Armenia. Though the center began in and is named after the town of Hadrut, taken by Azerbaijan in the 2020 war, the people who now come “are from all over Artsakh” and are predominantly survivors of the 2023 displacement, Tamrazyan said. The center’s goals include transmitting traditions and teaching skills so that attendees—especially older people and women—can sell wares at festivals and markets to earn income.

Sona, toying with a half-complete shatal—a traditional sock worn by brides originating from the Hadrut region—said she learned of the center in 2024 when she saw the city’s name on the sign while taking her kids to school nearby. Her husband is from Hadrut, while she hails from Martuni, also in Nagorno-Karabakh. After marrying, the couple moved to the Kashatagh region, which saw some of the most brutal fighting and much of which was ceded to Azerbaijan shortly after the 2020 war, pushing her family to leave then for Armenia. Though she has been in Armenia for nearly five years—longer than most Artsakhtsis, the majority of whom left in 2023—home is always on her mind; the name of her husband’s birthplace was enough to draw her into the building. Inside, she met people who knew her husband before the war, heard the unique timbre of the Artsakh dialect and learned about the different classes aimed at “transferring all of this consciousness to our children so that they can maintain the Artsakhtsi spirit and values.”

For the past year, Sona has been coming to the center every weekend, often bringing her children. “You come to a place like this and it is an environment that makes you feel close to your homeland,” she said. “Artsakh’s spirit is here.” Other women nodded and murmured in agreement as they inspected and straightened stitches across a tabletop tangled with yarn.

Nazik Hayriyan, who embroidered intricate geometry onto the bodice of an Armenian dance troupe’s uniform, chimed in: “When I come here, it does not feel like I am in Armenia; it feels like I am back in Artsakh.” She tells people upon departing for the center, “I am going to Hadrut.”

Hayriyan learned embroidery at the center last year and became a volunteer. She got more than a new skill, though. Losing home left her with “the kind of pain that no matter if the person next to you says they understand, they do not.” But practicing her traditional crafts, among others who experienced the same, “is the only activity that can help you forget.” Now, she said, she does not “feel my pain as frequently. . . . This place saved me.”

The center’s current location, a short drive southwest of the Yerevan city center, is its fifth since the 2020 war. Tamrazyan founded the center in Hadrut in 1995, and established branches in 20 villages in the subsequent years; both she and the institution were displaced from their home during the 2020 war and moved to Stepanakert, where the center’s basements provided refuge to local children during Azerbaijan’s attacks on residential areas in September 2023. Since then, the center has merged with its Yerevan branch, where it has been priced out of locations several more times.

Regina Grigoryan, who has attended the center since it was in Hadrut, where she grew up, now coordinates a partnership between the center and the YMCA to provide laptops and computer science classes. A recent graduate of the American University of Armenia, she came to Armenia for school as the 2020 war erupted; her family later joined her. To Grigoryan, the Hadrut Center is one of the few spaces to remain of her childhood, transplanted to her new city. “When you are here, you feel like there was no war,” she said.

Spaces and organizations like the Hadrut Center are critical for protecting cultural heritage, experts said, as Nagorno-Karabakh’s historical Armenian churches and monuments have come under Azerbaijani control. Many of these have been deliberately damaged or destroyed, according to the Caucuses Heritage Watch.

“After the displacement, we realized that it is very important to preserve the non-tangible culture, which is the only thing that we have some control on,” said Margaryan, motivating the Center for the Preservation of Artsakh Culture to create a coalition of 12 groups, including the Hadrut Center, to advance Artsakhtsi culture in Armenia and abroad. Intangible cultural heritage encompasses dialect, cuisine, crafts, music, dances and other traditions passed on through generations. But a lack of infrastructure and institutional support in Armenia threatens the intangible cultural heritage Artsakhtsis brought with them. The center’s existence is always economically precarious, Tamrazyan said. No one working at the center receives a salary; “we are the philanthropists; we are the ones working for free, providing the materials,” she said.

The right to retain, practice and transmit one’s culture is enshrined in international law. Beyond legal norms, Tigranyan said, culture also provides continuity and opportunity to develop community identity, something now also at risk for Artsakhtsis. Amid physical destruction in Nagorno-Karabakh and the socioeconomic challenges to preservation in Armenia, Tigranyan said, “we can see that displaced people have been robbed of their right to a future.”

The digital village

“17-year-old adolescent, son of a martyr, now a student, looking for a job. Very committed, hardworking and humble boy. Wants to support his family and gain experience.”

“Who is aware, to apply for citizenship, is it necessary to have a certificate of refugee status?”

“Baker, with knowledge of lavash, write to me. The hours are few, the salary is high.”

“I need tickets to the Noah-Budućnost game if anyone has one and is not going, willing to buy, even at a high price.”

“Hello, everyone. Now, what [government] aid will we get this month?”

Inquiries, life updates, resources and hot takes flow freely onto the timelines of Facebook groups such as “I need this thing,” which alone has 22,500 members. These groups have come to fill some of the chasm created when once tight-knit villages and communities, the social foundation of Artsakh, were flung across Armenia. Dislocated from physical proximity, former neighbors have been able to find each other again and discuss life’s daily happenings and troubles in cyberspace.

This phenomenon has made Facebook “one big village, Artsakh village, our digital village,” said journalist Sargsyan, who regularly logs on to see the daily posts from former neighbors—especially updates on who has died, when their funeral will be held and where. These posts have become a “ritual” for former communities, she said: “Without it, how would we know?”

Some of these groups originally launched on Facebook during the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh, when residents would take to the platform for offers and requests of mutual aid. Since displacement, new groups have sprung up where Artsakhtsis communicate about major life events, such as weddings and family deaths, that previously would have been village-wide affairs. In Artsakh, people were constantly involved in each others’ lives, said Tigranyan, the cultural heritage expert. “Absolutely everything was shared.”

“There is no [other] place to create this sense of community,” Sargsyan reflected.

These groups have also become vital professional and information resources for Artsakhtsis. Some people use them like newspaper classifieds, seeking employment or offering odd jobs. Many use the spaces to discuss news, politics and current events relevant to the broader refugee community.

Most urgent among these topics is the Armenian government’s support program for displaced families, which has provided monthly subsidies that in July 2025 were drastically and controversially slashed. Many remain confused about how much support they can expect and what the changes to the program mean for their family.

“If there are people from Artsakh who already have problems with their home due to the suspension of subsidies, please leave a comment or PM me. It is needed for reporting,” wrote CivilNet reporter Siranush Adamyan in a July post. Within 10 days, her post drew 129 comments.

People from Nagorno-Karabakh—who lost everything when they fled with what they could hastily cram into their vehicles or on their backs—are by and large extremely economically disadvantaged. A December 2024 needs assessment by the Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development (ACTED) found that 90% of displaced households relied on state support for basic needs, and the majority reported monthly incomes under the equivalent of $755 USD. “These incomes are insufficient to meet their basic needs, creating additional strain on their limited resources,” ACTED relayed.

This economic precarity coincides with high housing prices and significant barriers to obtaining employment, described to UNHR by numerous displaced Artsakhtsis. The government rolled out a housing certificate program in May 2024 that promised to provide Artsakhtsis loans through government partnerships with private banks in order to purchase or construct homes. But as of June, only 300 families out of the eligible 20 to 25,000 had redeemed certificates, according to Bedian at the Tufenkian Foundation. (The number of applicants grew to over 2,500 by August, the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs reported, according to Tert.am.) The reasons for such low uptake may include the requirements for eligibility, including that displaced people obtain Armenian citizenship. The virtual village bulletin boards are rife with posts from users seeking clarity on how to navigate the citizenship and housing certificate bureaucracy. Others comment in response with what they have experienced firsthand.

The last of the Artsakh government represents rights, hopes for return

The independence of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic was never formally recognized by the Armenian government, though a building in Yerevan has housed its “permanent representation” since 2007. Massive three-toned Armenian and Artsakh Republic flags, the latter bisected by distinctive white bands, flutter with the weak summer breeze. Against the building’s ivy-covered stone facade, a poster displays the faces of former Nagorno-Karabakh officials taken into Azerbaijani custody after the September 2023 blitz, now held in Baku without access to international trial and detention monitors.

The building has come to hold much more than unofficial embassy operations. Inside are key elected or appointed officials. The group can be described as a quasi-“government in exile,” according to Gegham Stepanyan, the human rights ombudsperson for the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, who has retained his role monitoring abuses and advocating for the rights of Artsakhtsis after September 2023 and who works from an unembellished office on the first floor.

In an interview prior to the Armenian government’s lawsuit seeking to invalidate the current ownership of the building, Stepanyan emphasized the purpose of the space and the representation inside is not “to create a parallel government in Armenia.” Rather, he and his colleagues are “just people who know their people, who know their problems, who know their psychology, mentality,” and who can therefore “be helpful to the government of Armenia in tackling the issues of these people.” The building is meant to be the “unifying place for our people” in efforts to “collectively protect our rights.” The gates and doors are always open, and anyone may enter, Stepanyan said, because the space “belongs to the whole population of Artsakh,” all of whom are invited to “come if you want, to preserve your identity, to preserve your dialect and to preserve all the hopes and inspirations connected with Artsakh.”

Different angles on this struggle unfold in adjacent rooms. Next door to Stepanyan’s office, Artsakh TV, the former public television company in Nagorno-Karabakh, films and broadcasts children’s programming in the Artsakh dialect. Groups also use the space to organize cultural events, exhibitions, film screenings and dialect classes.

The Council for the Protection of the Fundamental Rights of Artsakh Armenians, a formation of 40 non-governmental organizations from Artsakh and Armenia, meets downstairs. The group organized a series of protests in the months preceding the August 2025 initialization of a deal between Azerbaijan and Armenia, which drew thousands to Yerevan’s Republic Square demanding Armenian and international authorities advocate for displaced people’s right of “safe and dignified” return to Nagorno-Karabakh.

Protecting the right of return is not only of interest to the displaced community; it is crucial to long-term and broader regional stability, argued former Nagorno-Karabakh official Beglaryan. Normalization predicated on the erasure of a people is not sustainable peace and will fail on its face: “Without having justice, without having the return of our people, it is impossible to have peace,” he said. Affronts to Artsakhtsis’ rights are therefore a bellwether for the fortitude of the international system that purports to protect rights more broadly, cultural heritage specialist Tigranyan said. Without the right of return, Artsakhtsis will remain “scattered” across Armenia and beyond, spelling the extinction of an ancient culture and flattening cultural richness and diversity for everyone. “It would distort the balance of the world,” Tigranyan said. “It is not just an Artsakhtsi problem; it is everyone’s problem.”

Shameful the way that the Artsakhtsis are being treated.

This is the practical reality of Pashinyan’s treachery and betrayal.

Time for all those Armenian billionaires and millionaires in America to step up and start donating to the Artsakhtsis.

The Armenian State is controlled by Pashinyan and his hoodlums and when his State fails then Armenian Civil Society must step in and give what aid it can.

Thank you so much for shining a light on this shameful situation in a detailed way I haven’t read elsewhere to date.

Thank you for contextualizing the reality of displaced Artsakhtsis. These stories must be documented and shared.