My name is Kevork. In this year of 1915, I am 12 years old.

Tonight, it is black, no moon or stars—and this is good. For if they found us, me and the Turkish Jews, the Muslims would surely take their lives as well as mine, for I am an Armenian—a Christian. This group of kind and brave people found me, lost and alone in the desert hills, and indeed, because my family, my entire town is already dead, they are moving me from village to village toward the coast.

After many days, I can smell the salt in the air. On another cloudy night, I am placed on a small fishing boat. The sail is raised, and we silently slip across the water toward the west. Well before the sun rises, we meet a larger fishing boat. The hail from the new boat is in Greek; our response is in Hebrew. A strange but friendly conversation follows which results in my climbing aboard the bigger boat. I continue west, and my bearded saviors turn back to the distant shore, now faintly outlined by the rising sun.

During the next few days, we meet two other boats. Each time, I go from one to the other. The Greeks are friendly. Soon we reach the island of Samos, where I am taken aboard a ship. This is not a boat for fishing; it is for trading and carrying goods. The next weeks are unclear because I am working on the ship. I belong to the cook; I wash and keep things clean. This ship stops at many islands—always moving west.

We make our landfall at the city of Piraeus on the mainland of Greece. I live on the ship in the warmth of the galley, while the ship unloads. Some of the cargo goes into big wagons. When the wagons are full, I will go with them. My new friend, the cook, tells me that I will go across land to another port city, where the captain has a friend on a ship. They will take me to a far land named Italia. The cook says I must always keep moving west, following the sun; there, across an ocean, is a new life, a good life.

Riding on the wagons is nice. Sitting with the driver high up on the seat, it is much easier than walking. The only work for me is to water the big horses. After not so many days and nights, we reach the Port of Loutraki. But the ship is not here. The wagoneers are not concerned. They drink wine, sleep in the sun and teach me how to smoke.

The ship arrives. It’s loaded, fueled and provisioned, and off I go on another long voyage on the sea. Again, I work for the cook in the kitchen and take food to the crew and the captain. Each endless day is the same with the beautiful flat blue water and an almost white sky. Finally, I see land again – a place called Brindisi.

Everyone is speaking another tongue. It has another sound, Italian, not like Greek. I am not riding anymore – no boats, wagons or ships. I’m walking, and I am alone. Following a picture drawn by the ship’s cook, I am to keep going west until stopped by the sea. Then, turn north along the coastline and walk forever.

So started my long walk. When I left Turkey, it was the end of winter. Now crossing the hills of southern Italy, it is very hot under a big yellow sun. From time to time, I ride on a wagon with farmers, freighters or peddlers. But mostly, I walk. All around me is farmland. Food grows on the trees and vines. Good people, seeing a skinny little boy, offer to share their abundance. When charity or good luck fails, I must steal a little.

At last, when the sea is before me once again, I place the rising sun on my right shoulder, the sea to my left and walk. This land seems to go on without end. Climbing a hill means facing another; the crest of a mountain reveals another that is higher yet. Over the weeks of walking, I have grown legs like a mule. The weeks pass into months, and the seasons change. The nights are no longer warm as I skirt a big city. The road signs say R-o-m-a. One day, I come upon a large railroad yard, and some men who live there. They do not chase me away; they allow me to stay with them. During this time, in the land of the Italians, I learn to speak some of their words and understand many more. The men, very poor, say they are waiting for a freight train going north to a place called Livorno where they can find work. In a few days, we jump into an empty car and before the sun sets, we are off.

Riding the train is very nice. The men share their food and wine. I must take only a little, or they will think me a burden and cast me off. The train goes both slow and fast but stops only to take on coal and water. Two of the men tell me they want to earn enough money to buy passage on a ship to the “new world,” a place beyond the big ocean. The cook on the Greek ship told me about such a land; it is called America. They all tell me that is where I must go to start a new life. One of my train-mates has drawn a picture of a flag. It is the flag of this land and has red and white stripes with a blue corner.

One day, the men say that although the train goes on to a big city called Genova, they are leaving the train in Livorno because their jobs are there. That the train will continue in the direction I wish to go is very happy news. Another day and night riding the train is like a month on foot.

Genova is a large city. We are slowly moving through the outskirts when the train stops. Suddenly, I find that I am not as clever as I believed. The railroad police have me by the back of the neck. They are rough men, and they hit me on the legs with a stick. They take me off the train and into a building, the police station. They place me in a large room with an iron gate and bars on the window. There are others in the room – men who laugh and smile at me, but these smiles are not kind, they are evil. Fortunately, I am there for only a few hours.

The police take me before a man in a black gown and high white collar, a priest. With a stern face but kind eyes, he brings me to a place full of women in white gowns and odd-looking hats. After sitting me down for food and milk, one of the oldest women takes me out to the small river behind this place. She takes off my clothes and scrubs me from top to bottom with strong soap – especially the head for lice. She takes me back inside, gives me some clothes and leads me to a room with many beds and other boys.

It has been a long day with many surprises, but I have saved the flag picture. I fall asleep but wake in the middle of the night. It is tempting to stay here with the food and the bed, but the call of the new life in the west draws me into the night once again.

As I move down the dusty road once again, I find that the shoreline I follow first turns west and then southwest. This is a good thing for two reasons. It is winter now; the air is cold and the rains chill to the bone. Staying along the sea and away from the highlands to the north will be less cold. The second reason is even more important. War. There is war in Europe, and this can mean hunger and death.

Moving forward, the sound of the language is changing from Italian to French. After passing Bordighera, I steal across the border post and follow the signs reading Monaco. As I walk and walk, I learn to use a good tool – the smile. People seem to like you more if you smile.

The winter is spent moving along the coastline of the south of France. I mostly walk, but I sometimes find a ride in a wagon or on the back of a horse.

Shortly before the city of Cete, I come upon a canal that flows along the coast. This is truly a gift from God, for the people on the canal barges will let me ride with them for very little work.

For weeks, the barges carry me gently to the west. As I learn enough words, I can understand that the canal will go to a place named Toulouse. There it meets the great river “Garonne.” The bargemen are very kind, but even more so are their wives, great fat women with many children.

When we reach Toulouse, I stay with a barge family until they find another barge family, one that will go further west down the Garonne River. I say many prayers of thanks, because this boat and this family tell me they will take me with them all the way to the ocean port. When I show them the picture of the flag, they say they have seen ships flying such a flag.

Weeks, maybe months later, we reach where the river, now so wide I cannot see the other side, empties into the sea. I leave my barge family and go to the docks. There are many ships, each bigger than I have ever seen. After a day, I find a ship flying the flag of stripes and stars.

Without difficulty, I get on board by hiding on a pallet of cargo that is lifted high into the air and then lowered into the belly of the ship. I hide in a small room full of ropes and barrels. In less than a day, I hear the rumbling of the big engines and then the rolling of the ship as it becomes free of the land.

I know I must wait, but thirst drives me from the hiding place. I am found by one of the crew members and taken before a man of authority. He wears a clean white shirt. And, almost as if they knew of my past ship voyages, I am given to the cook. As I have learned, if I obey, and quickly, the cook and the others would be kind to me.

During the next several weeks, as we sailed across the springtime sea, I try hard to learn some of the Americans’ language. Almost two years prior when I left Turkey I thought like a child, but now as we near my new land, I must think like a man.

Before I am ready, the word comes that land is on the horizon. Yet, the ship’s voyage is not done. For some days, we slowly sail up a very large bay – Chesapeake. Then we dock at the port of Baltimore. From the ship, a mate takes me to the authorities in the city.

These people ask me many questions. I do not understand them, and they do not understand me. They leave me in a room. I am alone. Looking down a long hall I see sunlight – an open door. Before they can return, I am out the door and running down the busy street.

I am here, America! I have come!

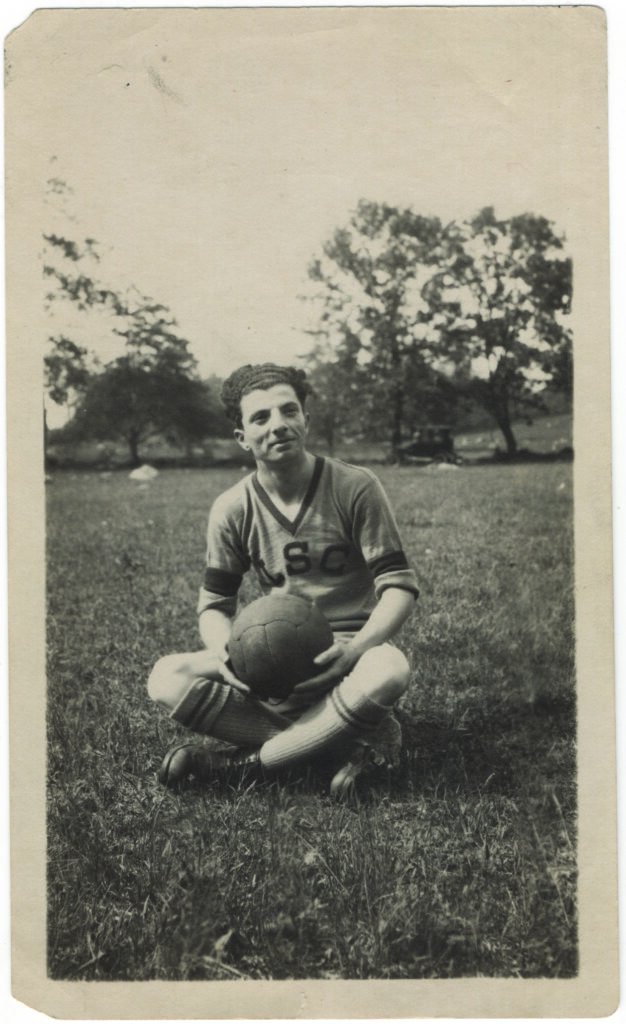

My name is George. In this year of 1917, I am now 14 years old.

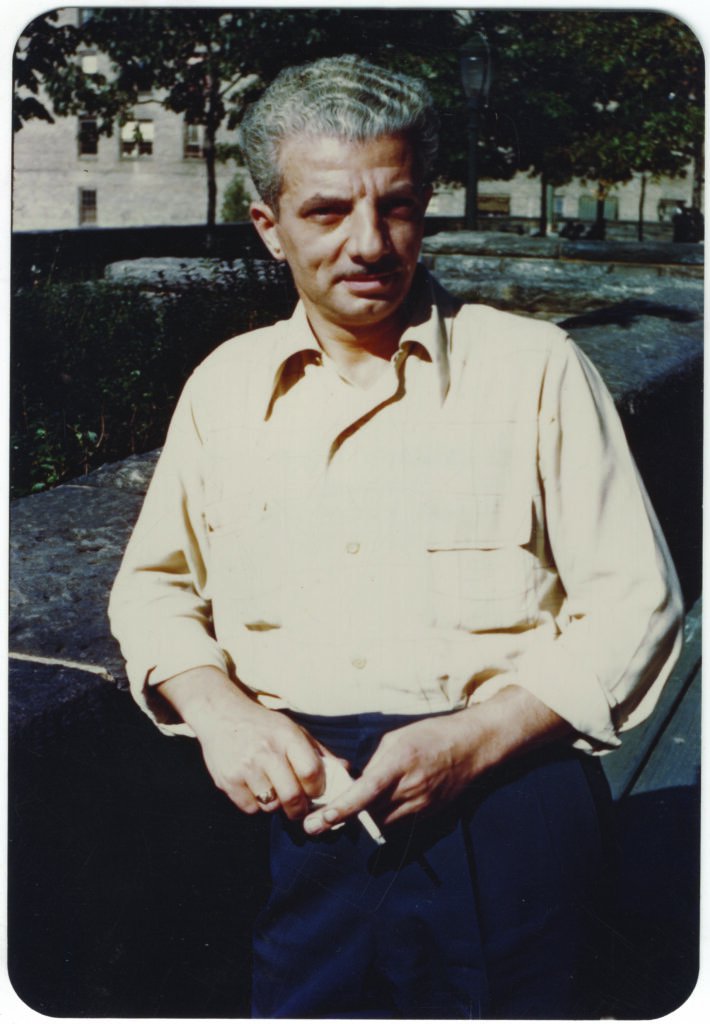

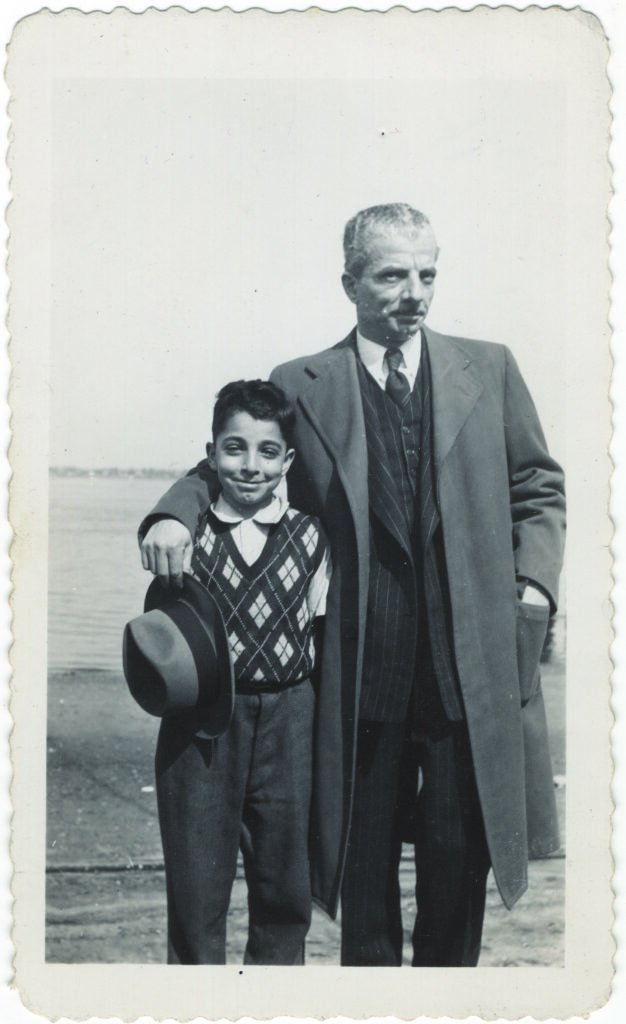

So begins the story of one of the most patriotic Americans I have had the honor to know. These are my father’s recollections. In the interest of continuity, I beg that you accept some poetic license rather than absolute chronology and geography. – Raffi G. Kutnerian

I knew it would be a great story–even better with pictures! Congratulations, Raffi!

Thank you Raffi!

I have some similar but not as elaborate or difficult journey of live as your honorable father Kevork’s to reach to the shores of America.

I was about the same age as Kevork when a miracle strike me & Trip to America began.I like to share it, some times in the future.