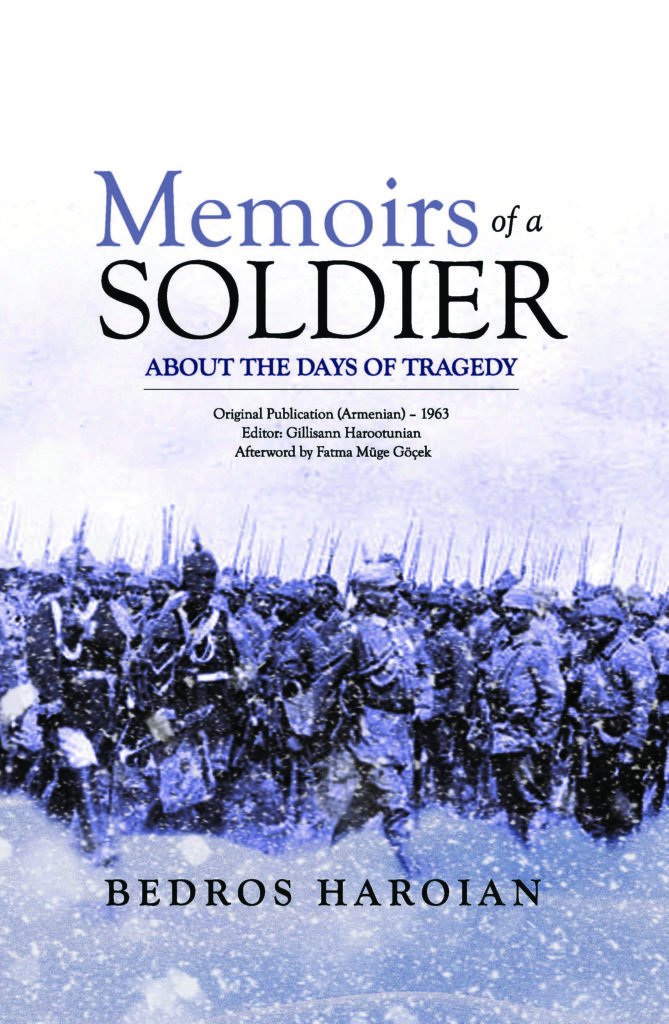

Memoirs of a Soldier: About the Days of Tragedy

Memoirs of a Soldier: About the Days of Tragedy

By Bedros Haroian

Tadem Press, 2022

480 pp.

Hardcover, $42.95

As we crossed the centennial of the Armenian Genocide, more and more memoirs written by survivors are becoming accessible, either for the first time or translated into English/French. Among the latest additions to this growing literature is the English edition of Bedros Haroian’s Zinvori Muh Husheruh: Arhavirki Oreren, originally published in Armenian in 1963. Under the editorship of Gillisann Harootunian, PhD, and an afterword by Fatma Müge Göçek, Haroian’s translated memoirs, Memoirs of a Soldier: About the Days of Tragedy, have been published by the Tadem Press (Fresno, California).

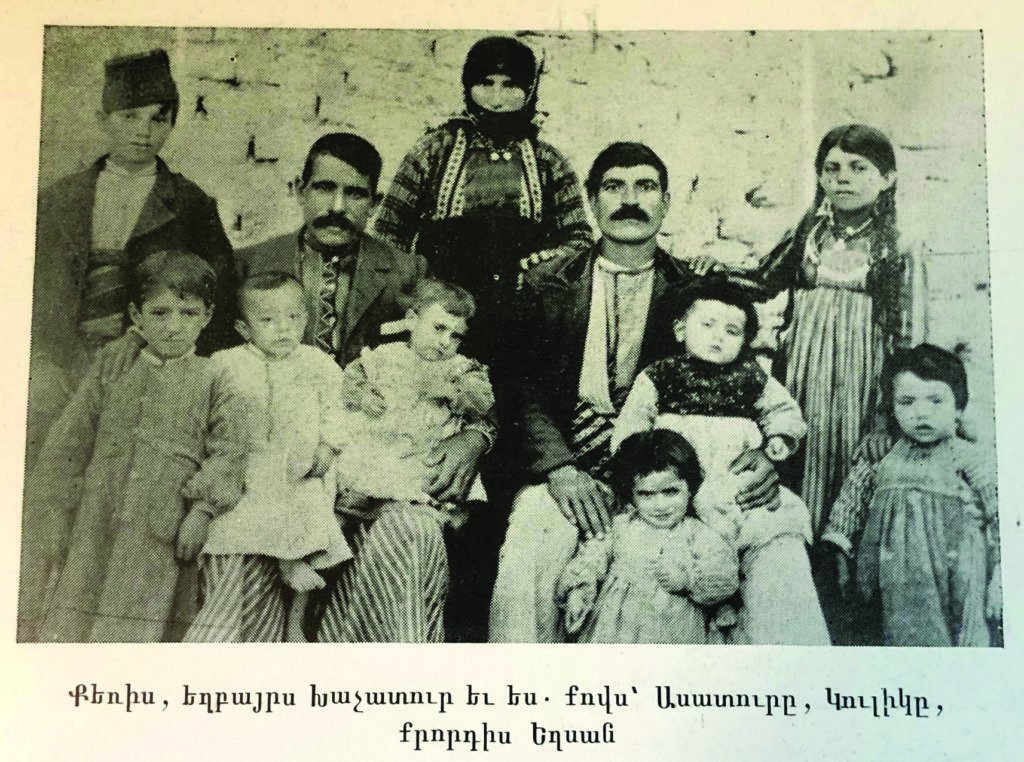

There is an abundance of genocide survivor testimonies and memoirs, broadly known as the Houshamadian literature in Armenian. In this respect, rendering Haroian’s story accessible to an English-speaking/reading audience is a welcome contribution and provides rich material for the study of Ottoman-Armenian life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many aspects of the work share some of the same characteristics of other Houshamadians, including a thorough description of Haroian’s native village Tadem (Kharpert), a portrayal of his extended family and the traditions that made up Ottoman rural life in Anatolia. Therefore, the first chapters of the book are vivid accounts of Armenian-Turkish relations in the larger region of Kharpert, social and economic ties between Turkish landowners and Armenian peasants, as well as the situation in Tadem after the 1895 Hamidian massacres—an important turning point that pushed the young Haroian to join the revolutionary committees.

The second major feature that characterizes this work is the thorough description of the author’s conscription into the Ottoman Army on the eve of World War I and his participation in the battles on the Eastern Front (Ottoman-Russian), including the infamous Sarikamish campaign (December 22, 1914-January 17, 1915). While the fate of Ottoman-Armenian soldiers during the war is one of the most understudied aspects of the Armenian Genocide, Haroian’s memoirs shed fresh light on the ordeal of many Armenian conscripts who shared the same suffering as their Muslim counterparts during the fighting yet were later disarmed only to be integrated into labor battalions where many perished. Therefore, Haroian’s memoirs are not only an Armenian soldier’s perspective on the Battle of Sarikamish and the early months of the war, but they are also an insider’s account of the Ottoman general mobilization, the toll that the war had on the local population and the Ottoman authorities’ increasing radicalization toward the empire’s Armenian population, as Haroian describes the horrendous massacres committed around Garin/Erzurum and in his native Kharpert.

It was in the spring and summer of 1915 that Haroian also became an eyewitness of the Genocide. He recalls the large caravans of deportees who were forced to march only to be killed by ambushing gendarmes and bandits. Haroian, who was serving in a labor battalion, witnessed the carnage at Keotur Bridge and was ordered to bury the bodies of the raped and slaughtered Armenian women and girls, a daunting task he describes in detail. Subsequently, he decided to escape with some fellow Armenians. As soon as they approached the villages in Kharpert, they made plans to cross into the Russian side, as the Czarist Army was fast advancing in Eastern Anatolia in 1916. Filled with a desire for revenge, he wanted to reach the Armenian volunteer battalions under the comradeship of the Russian troops, which he accomplished with the assistance of some Kurdish chieftains in Dersim.

From 1916 onwards, Haroian was a soldier in the Russian Army. Soon after the Revolution of 1917, Russian forces began to withdraw from Eastern Anatolia, leaving Armenian volunteers alone against an offensive Ottoman Army. Haroian traveled to Tiflis where he met General Andranik Ozanian and joined the soldiers fighting for “Armenian freedom” in the Caucasus (p. 212), using his military experience at the service of the First Republic of Armenia (1918). Despite his arrest and torture in Baku, he succeeded in making his way to Cilicia and joining the Armenian Legionnaires (originally known as the Legion D’Orient) in 1919, a small auxiliary force under French command that help the Allied Forces’ takeover of the region after the Armistice of Mudros (October 30, 1918). In this respect, Haroian’s account is a timely addition to the growing materials on the history of the Legion, the legionnaires’ disillusionment with the French authorities and their final abandonment of Cilicia, bashing the hopes of many Armenian survivors and legionnaires (including Haroian himself) for an independent Armenian statehood.

Memoirs of a Soldier: About the Days of Tragedy is a critical and a welcome addition to the accounts by Armenian Genocide survivors. What makes this book uniquely useful for students and academics in Middle Eastern Studies broadly defined is Haroian’s involvement in the Ottoman, Russian and French armies, a rare feature that not many contemporaries shared. Therefore, his testimony brings a fresh perspective to several aspects of the history of the Great War, the Armenian Genocide, Armenian political parties in the early 20th century, the turmoil in the Caucasus 1917-1919 and the early years of the French Mandate in the larger Levant. In this respect, it serves as an insightful and helpful resource and a primary source that can be readily used in the classroom as well as be of interest to a broader audience. The extensive footnotes guide the reader through the many events and characters that Haroian mentions in the memoirs, making the work much more accessible to non-specialists.

Very helpful review!