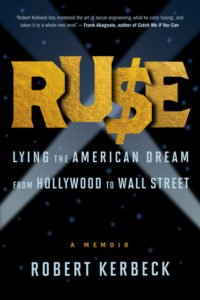

Robert Kerbeck is the author of the brand new true crime memoir RU$E: Lying the American Dream from Hollywood to Wall Street about his career as an actor turned corporate spy. The Weekly’s Paul Vartan Sookiasian spoke with Kerbeck, not just to discuss the critically-acclaimed book and what might be next for it, but also the original secret in his life of espionage, his Armenian ancestry.

A.W.: Congratulations on the publication of RU$E. There’s so much to say about it, but we want to start by delving into your Armenian ancestry.

R.K.: The story begins with my great-grandfather Garabed Kerbeckian, who left the town of Arapkir after the Hamidian Massacres of 1895. He traveled the world looking for a place to raise his family in safety. He decided that Philadelphia was the perfect place. My grandfather was born there in 1901.

A.W.: Our readers might not recognize your name as Armenian because it lacks the typical ending, but you say there’s a reason behind that.

R.K.: When my great-grandfather arrived in the late 1800s, he made a living repairing horse carriages for well-to-do Philadelphians. Seeing the transition to motors, he became an automobile dealer and was one of the very first in the city. Somewhere around this time, Garabed dropped the –ian, likely to better assimilate into America. Kerbeck has a bit of a German sound to it, and Philadelphia had a large German population. Unfortunately, as we all know, immigrants are discriminated against, especially those new to the country, and Armenians were no exception, so being a smart businessman, he knew the change would give his business the best chance for success.

A.W.: For reasons we won’t give away, RU$E describes how your father’s birth had to remain a secret from the wider Armenian community, which meant he wasn’t able to connect with his Armenian heritage. Describe what this has meant for your own sense of being Armenian.

A.W.: For reasons we won’t give away, RU$E describes how your father’s birth had to remain a secret from the wider Armenian community, which meant he wasn’t able to connect with his Armenian heritage. Describe what this has meant for your own sense of being Armenian.

R.K.: My Armenian story isn’t a very traditional one, as I didn’t grow up with Armenians. I always felt this deep connection to Armenia, and yet because I wasn’t raised in the typical Armenian household it was hard to investigate that fully. As I got older, I started doing research into what this part of me was all about. One of the earliest instances occurred after I graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and moved to New York to try my luck at becoming an actor. It turns out that I was hired to perform some unpublished plays by William Saroyan at the Actors Studio specifically because of my Armenian connection. Over time, I started meeting Armenians (moving to LA certainly helped with that) and learning from them.

A.W.: I think even Armenians who have grown up in an Armenian community have always felt a bit of disconnect from their history because of how we were cut off from it in many ways by the Genocide. For most of us, our family trees stop at 1915. So many potential cousins were killed, disappeared or never born, and the towns where our ancestors lived have had their Armenian character erased. So in a way, like you, our entire experience in the diaspora has been one of trying to figure out what and who we are, what being Armenian means to us.

R.K.: I started out by reading everything I could about Armenia. I think at this point I know a lot more about Armenian history than a lot of Armenians do! Just like how you reference lost family, I also took a particular interest in my Armenian genealogy which spurred me to reach out to relatives I had never gotten a chance to know because of my grandfather’s ‘big Armenian secret.’ It’s been a process of trying to put the pieces together, and it’s been wonderful to re-establish lost family connections. I just got to meet more cousins for the first time recently when I was in town to do a book signing for RU$E! What’s so fascinating is that all our stories matched up. Here I was talking with people I had never met, and yet the stories passed down to each of us synched up almost perfectly. It was really cool to get that kind of verification, and now I can be confident in sharing these stories with my own family.

A.W.: Besides the autobiographical aspects of RU$E, has your Armenian background found its way into your work?

R.K.: While I’m only part Armenian, for me that part seems to have called out to me. I feel like I’ve had to respond to this call, which has included learning to speak some conversational Armenian, of which I’m really proud. I think this comes from learning what our people have been through over the past centuries, and I think there’s something about me as a writer that had to understand it. Recently I had a short story published in the Armenian literary journal HyeBred in which the main character is Armenian, which I was only able to do because I answered that call. Somebody needs to tell those stories, as not many cultures can talk about nearly being exterminated and coming back from that. This is important not just for other Armenians, but even more so for those who are not Armenian so that others can understand what Armenians have gone through.

A.W.: That idea reminds me of academic Talin Suciyan’s recent work calling for more attention to be paid to the endangered Western Armenian language because of all it has to contribute to world literature. She describes how it contains many works which confront us with the experiences of genocide, survival and the survivor’s silence. For us, Western Armenian is our beloved mother tongue, but even we likely take for granted the profound meaning within it, how it challenges our ability to think and write about one of history’s darkest pages. There’s such a need for us to continue telling these stories and making these works more accessible to international audiences so they can take that rightful place in the global conversation.

Now turning to your own work, I need to ask: how did you find yourself a job as a corporate spy? I can’t imagine it’s the kind of position listed in a job posting. And what exactly did you do?

R.K.: That’s true! It certainly wasn’t something I sought out. While I was a student at Penn, I got bit by the acting bug. I wanted to move to New York to become a professional actor, but it was an intimidating idea so I went to work in the family car business for about a year. It wasn’t for me though, so I finally got the guts to pursue my career. Of course, like any actor I needed a day job to get by. The only person I knew in New York was my college roommate’s brother who showed me the ropes. One day, he casually mentioned getting a new job, but when I asked him about it he got very vague. It seemed like it was some sort of telemarketing job, and coming from car sales I figured I could do it, so I asked him to get me an interview. Instead of being asked into an office, I was sent to this palatial apartment on the Upper East Side and met with a woman who never even looked at my resume. Instead of telling me about the position, she just asked me about my family… and the next day I was told I was hired. I went in for training, still not knowing what the job was. As the training progressed I began to realize why they don’t tell you about the job ahead of time! We were obtaining private information on Wall Street firms about their employees, their teams, internal rankings, future plans, acquisitions, that we would then sell to their main rivals.

A.W.: In the book, you talk about what, and who, makes for a good spy. Your boss had a very intriguing philosophy on that. Can you tell us more?

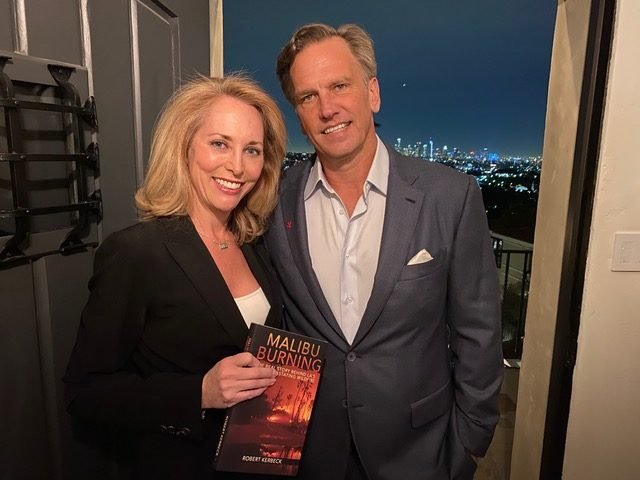

R.K.: My boss was a rare woman to be running a Wall Street firm at the time, and I was one of the first and only men she hired because she didn’t think men made good spies. Recently I got to do a book event with my high school classmate, former CIA spy Valerie Plame – what are the odds that two spies graduated together from the same Philly high school? Valerie said, “Of course women are better spies! They’re more empathetic, more adaptable and chameleon-like to every situation.” This meant as the new guy I had my work cut out for me, so I needed a different approach. While the female spies targeted junior people within a given company, I went directly to the big executives, who at that time were mostly men. I was able to go ‘guy-to-guy’ and soon they were telling me anything and everything I wanted to know.

A.W.: Corporate spying sounds fascinating, like it was made for TV or a movie, and I understand that the book may be headed in that direction.

R.K.: Yes, RU$E is in development for a streaming TV series. A Hollywood production company with numerous shows on air including Showtime’s Your Honor with Bryan Cranston pitched it to a major studio, and we are now developing the entire first season.

Love Paul’s writing about Armenian abd this interview was just great