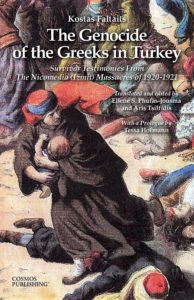

The Genocide of the Greeks in Turkey: Survivor Testimonies From The Nicomedia (Izmit) Massacres of 1920-1921

The Genocide of the Greeks in Turkey: Survivor Testimonies From The Nicomedia (Izmit) Massacres of 1920-1921

Kostas Faltaits

Translated and edited by Ellene S. Phufas-Jousma and Aris Tsilfidis

Prologue by Tessa Hofmann

New York: Cosmos Publishing, 2016

155pp.

The history of the Ottoman town of Izmit during World War I and its immediate aftermath can be summed up by the phrase “first they came for the Armenians, then they came for the Greeks.” Izmit, which was known as Nicomedia in Antiquity, was a relatively small port city with a population of 13,000 with a strong Armenian and Greek presence. Indeed, Izmit was an important Armenian center in the Ottoman Empire since the 16th century. The absence of major Muslim sites in the region made it a welcoming place for Christians, Armenians as well as Greeks. An official British Report on Anatolia published in 1920 notes that by the time World War I broke out, Izmit was becoming increasingly prosperous thanks to its proximity to the Ottoman capital Constantinople—about 100 kilometers (60 miles) to the northwest—and also because its healthy climate and good railway communications. The port’s hinterland consisted of fertile agricultural lands and forests. Cereals, especially maize and seeds, were grown in large quantities along with fruit, which together with poultry and eggs found a ready market in Constantinople. There was also a thriving silk industry in the area of Izmit.

The fate of the Armenians of Izmit during the Armenian Genocide has been reported in several sources, most recently by the blockbuster study by Israeli historians Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi entitled The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of its Christian Minorities 1894-1924 published by Harvard University Press in 2019. The authors describe how soon after the outbreak of World War I the Ottoman authorities began targeting the Armenian populations in the town and its surrounding area by falsely accusing them of possessing bombs or supposedly being part of a French spy ring. In April 1915 many local Armenian leaders were arrested and there followed more arrests until in July 1915 when notices appeared informing the Armenians that they had to move. A month later the deportations started. A total of 120,000 Armenians was deported from the entire province, according to British estimates, and only one in four survived the ordeals that followed. About four thousand remained, but only to become victims of the new round of genocidal acts, which would target the Greeks and all Christians in 1920-1921.

Those actions against the Greeks are described in detail in reports filed by Kostas Faltaits, a Greek newspaper reporter, which were collected and published in book form in 1921 in their original Greek language with the title “These are the Turks! Narratives of the Massacres in Nicomedia” using the ancient Greek name for Ismit. Soon after, the Greek government translated the book into French under the title Volilà les Turcs! Récits des Massacres d’ Ismidt. Now, thanks to the work of translators Ellene S. Phufas-Jousma and Aris Tsilfidis, who also edited the texts, we have the accounts in English. Their publication is augmented by an introduction by Tessa Hofmann, a scholar specializing in genocide studies.

Faltaits arrived in Anatolia to cover the Greek military expedition for the Athens-based newspaper Embros. Greek forces had landed in Smyrna, a bustling commercial port-city on the Anatolian coast in May 1919 following the decision of the Great Powers that Greece should control that region, pending a referendum that would decide its future and the partition of the Ottoman Empire. Turkish nationalist resistance to the Greek presence entailed clashes with the Greek troops around the Smyrna region and increased attacks on ethnic Greeks all along the Anatolian littoral and further inland. Soon, the Greek forces pushed eastward into the Anatolian hinterland and northward toward Izmit in pursuit of their nationalist attackers and in order to defend the victimized local Greek populations. Faltaits followed the Greek army units that arrived in the Izmit region in the wake of the attacks suffered by the ethnic Greek population, as well as the remaining Armenians.

The book consists of nine eyewitness accounts by Greeks of Ismit and the surrounding region that Faltaits collected, as well as accounts of his conversations with the Armenian Metropolitan of Nicomedia, Stephan Hovakimian and Benjamin Lazian, a hotel proprietor. The accounts make for difficult but obligatory reading because they include detailed and graphic accounts of the violence perpetrated on the Christians of the region on civilians of all ages, including young women and children. The violence was random as it was vicious and included rape, sexual mutilation and torture. The narratives Faltaits recorded also convey the sense of the unpredictable and inconsistent process that ethnic cleansing took in the Ismit area. Initially, the Greeks invoked the good relations that Christians and Muslims had enjoyed in the past, hoping that by submitting to the financial extortion that the Turks demanded they would at least stay alive. But the situation quickly descended into chaos, as demands for food, money and gold were followed by demands for young women to serve in sexual servitude. After a while, it became clear that the randomness was being succeeded by a pattern of violence dictated from above with the goal of simply eliminating the presence of the Christians.

The additional value of these accounts is that they are not one-sided despite the overall emphasis on the brutalities of the Turkish brigands and nationalists. There are instances when Turks protected Greeks and vice versa, and there are descriptions of the reprisals inflicted on the Turks by the Greek army when it arrived in the area in the wake of the massacres. As Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi suggest in their study, punitive actions taken by the Greeks were much more limited and of a much smaller scale than those by the Turks. The accounts gathered by Faltaits are also helpful in understanding the context and extent of the Greek actions.

Overall, this book provides both graphic details of the genocidal actions directed against the Christians in Izmit and the surrounding regions and a broader historical contextualization thanks to Tessa Hofmann’s prologue. There’s also a helpful note by the two translators and editors Ellene S. Phufas-Jousma and Aris Tsilfidis, biographical information about Kostas Faltaits, as well as an introduction by his son Manos Faltaits, a chronology of the events and, finally, several of Faltaits’ reports that appeared in the Greek newspaper Embros along with translations in English. It is a book that will benefit all those who are interested in the fate of the Christians during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and can also be very helpful to younger generations who are studying those events in high school or in colleges and universities.

Was Ancient Greek (koine) spoken and written in Anatolia in the early 20 th century?