Stephen Kurkjian is your quintessential Bostonian: a red-blooded and Red Sox-loving native of Dorchester, blessed with the gift of gab and a hearty appetite for a good story. Those last two things, he made a career of. He’s retired now, but for the last half century, Kurkjian has covered some of the most important events in our nation’s history for the Boston Globe newspaper, where his investigative work has earned him three Pulitzer prizes. He is a founding member of the award-winning Spotlight team, whose hard-hitting local stories—which include the clergy abuse scandals of the early 2000s—have helped make Boston a better city for all.

But Boston is, if anything, a tribal sort of place, and Kurkjian has always felt a certain privilege at being a member of one particular tribe: the Armenian diaspora, a long-standing immigrant community that has made a name for itself in the area since escaping genocide over a hundred years ago. It wasn’t until later in life—too late for his own liking—that he realized his family’s history extended far beyond the dark-haired loudmouths he grew up with on the streets of Dorchester. And much of his recent work has been spent documenting what he’s found.

In our latest episode of the Armenian Weekly Podcast, former editor Karine Vann sat down with Steve to talk about growing up Armenian in Boston, his time at the Globe uncovering some of the greatest scandals of our era, and literally everything in between.

The transcript of our conversation is below. If you liked this interview, you can be the first to know when future episodes are released by subscribing to our newsletter. You can also find us on iTunes.

***

Karine Vann: Steve, thank you for speaking with me today.

Stephen Kurkjian: Thanks for having me, Karine.

K.V.: Great. So we’ve got a lot to talk about. I’d like to spend parts of our conversation talking about your experience as a veteran of American journalism. You’ve covered some of the most major events in recent US history. And also about your experience as a member of the Armenian Diaspora in the Boston area, where, you know, the Armenian Weekly newspaper is based—and the ways in which those aspects of your identity may, or perhaps may not, intersect. So I think that will guide our conversation a bit. Maybe we can start by you telling me a little bit about your career. How did you eventually get to the Boston Globe?

S.K.: The Globe was located in Dorchester neighborhood of Boston and my family and I grew up in Dorchester. My father was a survivor of the Genocide. Came here as a mere lad and married my mother, whose family was living in Dorchester—both Armenian. And I thrived in Dorchester, both as a very sort of protected member of my family—larger family, cousins all around. But also as a boy of the streets, who learned how to socialize in a very diverse neighborhood, with kids of all ages and ethnicities. And it was a real melting pot. And I love sports, and just engaged with the kids. One other thing I learned from the streets as I forge back into my past is a sense of fairness and that was really driven home to me. Because some families did not seem to have as much access to opportunity as my family had. And maybe it was because my mother and father and grandmother and uncle and aunt lived in the same house with me. And I was watched over and protected and guided in the right directions. And other kids may not have had 2 parents, if not grandparents, living in the same house. People were not watching over them, so they were not on the rails, and they struggled because of not being nurtured and guided and protected and also warned about doing things the right way. So, that sense of fairness of unfairness in life really guided me as I grew older and sought a career, wanted to have a feeling of trying to make things fair for everyone—as fair as possible as outside forces could allow.

K.V.: It’s interesting that you mention this idea of fairness because I myself have thought a lot about what is it about the Armenian experience that lends us to these types of careers? And for me, I think this priming from a young age, learning about the injustices of our ancestors—you know, a lot of us come from the survivors of genocide, and I feel like that early antennae to justice has a lot to do with where we end up in life. It’s interesting to hear you make this other comparison, where you had a very protected family unit.

I would pick up the phone in my office and say, “This is Steve Kurkjian.” And people would give me a tip or two. But they always were interested—Boston’s a very tribal city—they always want to know who you are by your ethnicity.

S.K.: I hear what you’re saying as far as having a zeal for fairness and justice. As I got into my career as at the Boston Globe as a reporter… you know, each of us had our own phone numbers and phones would ring on my desk in my office and I would pick up the phone in my office and say, “This is Steve Kurkjian.” And people would give me a tip or two. But they always were interested—Boston’s a very tribal city—they always want to know who you are by your ethnicity. You’re Italian, you’re Irish, you’re Jewish, you’re Hispanic, whatever it is. “What is that, Kurkjian? What is that?” And I said, “It’s Armenian.” And invariably—this is not made up—you would hear a pause in the voice and they’d say, “Armeeeeenian.” And they were harkening back to their experience with an Armenian. And in-ev-it-ab-ly that experience was a positive one. Whether it was the tailor, whether it was the doctor, whoever, whatever experience they had. They had a positive experience with the Armenian people. And as a reporter, you like to be known by people as someone who can be trusted. And that really struck me. That the Armenian ‘brand’—this small tribe of unimportant people, which we are in every community in every state in the country—we get known by the deeds that we have done. And that, because my family was in my face all the time about doing things the right time, like I’ve said before, lose your arm before you lose your name. That was driven home to me. So a sense of, “Hey, wait a second. It’s not just me and my family. It’s us. It’s the Armenian community that this matters about.” And whether it was lawyers or politicians or regular businessmen, family people, people had a good experience with the Armenian people. And that drove home that need to do things the right way. And that carried on to my career. My mother said to me—my mother had worked at the Boston Herald as a librarian. And before there were computers, one of my colleagues who knew her at the at the paper said, “Before there were computers, there was a Rosella Kurkjian.” She was so determined to make sure she got the information for the reporter who needed something on deadline for a story they were writing. So, that carried over to me. And she said to me, “You’ll have a wonderful time as a journalist. You’ll see the world. But you won’t make enough money to raise a family.” This was back in the sixties.

K.V.: Even then!

S.K.: Even then!

K.V.: And we all talk about this like it’s a new development.

S.K.: [Laughs] No, well, there was a golden age of journalism. Which I thankfully was part of, but back then in the sixties, before Watergate, before investigative reporting, which became an important element of journalism and put us quote on the map unquote, you know, people were struggling. So she said, “You better get another profession.” So I did, I went to law school. And enjoyed that immensely. Loved the practicality, that you could find answers. There were real answers. It wasn’t like the subtlety of poetry or sublime writing. It was hard facts. And I loved that about the law. So I went to law school and I got that. I never practiced, but it helped me immensely in getting information… You become a much better writer if you get a master’s in journalism. But you become a much better reporter if you get your master’s degree in another field.

K.V.: Right, that’s how I went about it, too. Never would have imagined I would end up in journalism with a musicology master’s degree. So let’s talk a little bit more about how you went from this young Steve Kurkjian on the streets to eventually in the Boston Globe circuit. What happened between law school and then?

S.K.: Well, I was going to law school nights in the late sixties. And two major stories happened that really guided my—I was at the Globe. I had just started a year before. And I was covering the Vietnam protests. And I was really interested in that. This was really… The streets were alive with protests. Every day, every campus, every church was involved in this, especially in Boston, trying to raise the level of dissent towards the war. And that was my major responsibility. Well, ‘69 in August, there was an accident on the island of Chappaquiddick right off of Martha’s Vineyard and Senator Kennedy was involved, a leading figure in Massachusetts, the brother of John and Bobby Kennedy. And a woman had been killed and there were lots of questions about the circumstances of the accident… I was at my summer home on Sunday morning in Manomet, Plymouth, a few miles away and I got a call. In fact we didn’t have a phone, my neighbor got a call and said, “Steve, it was an editor at the Globe, he wants you to go to Martha’s Vineyard to help cover it.” So I zipped down there thinking the reason I got sent there was because of my law school background. It wasn’t, it was only because I was closest. [Laughs] Being in Plymouth, I was closest to the ferry in Falmouth. So I got over there and I covered it. And I broke some pretty important stories, much because of my background in law. And that put my name on the front page on an important, essential story. So I was really involved in that story. Well, the next story, I was told that I had to take the week off because I was now staff at the Globe, so I had to take the week off. I saw in the paper there was a rock’n’roll concert in upstate New York, so I said to the young man beside me, “Hey, do you wanna go out there?” The best bands of the time: Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix. And I was a rock’n’roller then and I continue to be a rock’n’roller. And I said, I’m gonna go.

K.V.: And the Globe was not planning to cover this already?

S.K.: The Globe was not, in fact, planning because it was only planned to be 80,000 people. Well, it turned out to be 400,000 and it turned out to be a very big cultural event called Woodstock. Well, I went and it took me most of the day to get there, but I got there and they called me and I called in and they said, “Start filing.” And I didn’t know what they wanted me to file because it seemed like everything was going to go on as usual.

K.V.: What do you mean by start filing?

S.K.: Start filing means start reporting, start sending us material. This is a front page story now. And I happened to be there. Well, that’s happenstance, but…

K.V.: Lucky them.

S.K.: Lucky them. And so I said, “What’s going on?” And they said it’s going to turn into a Vietnam protest. Now, the same thing of my being on the scene and being a reporter, trained and going and asking people what’s going on, that worked in Chapoquitik, worked here. And I went down to the podium, met up with a couple of the organizers, and they said, “No, no, no—it’s not being called off. This is not a Vietnam war protest.” And having covered Vietnam war protests, I knew that. These were the younger brothers and sisters of the protestors. These were kids that just want to enjoy a weekend of rock and roll, smoke some dope, relax. This was not a protest. So I phoned my story in that night. And it turned out to be right. But it proved to me that doing what you’re supposed to do as a reporter, getting up close, asking the questions, being very open and transparent with what your interests are—I was being told by the ASsociated Press that the government was going to shut down the concert. But when you go right there and did what we do as reporters, you found a totally different story. Well, as I drove home, it took me 5 days to cover the whole thing. The thing went on for three days and I stayed for a couple of days. Gee, this really does work. This is a really essential element in what we’re supposed to be doing as journalists.

K.V.: What do you mean, getting up close?

S.K.: Getting up close, asking questions, getting information, filing it, and helping the reader understand that something amazing is happening here. And I was getting it correctly. I was telling the story in a correct way. So I decided as I was driving home I’m going to stay as a reporter. I’ll get my law degree, I passed the bar, which I did. I passed the bar. But I was never gonna leave the job of reporting.

***

S.K.: Two years later they started the Spotlight team. Somebody tapped me on the shoulder and asked me if I would join it. I said, “Gee, it sounds interesting, but only for a year. I don’t wanna give up my bylines and also my chance to cover statehouse political stuff.” And they said, “Don’t worry, we’ll let you stay on for a year. Your law school training will help you.” Well I stayed on not a year, but 16 years. And during that 16 years, the team won two Pulitzer prizes and I was the editor on the second one.

The more local you become, the more effective you become in people’s lives. I’m not just talking about the school lunch program.

K.V.: What were those stories?

S.K.: The first [Pulitzer prize award] was on the the city of Somerville. There was corruption going on and old time politicians giving out contracts without any approvals that were necessary to their friends and family. And lots of people got indicted for tax evasion and all sorts of things. You know, this was Somerville at its worst, very industrial insider ball game going on. And I think we cracked that. And then later, my editor said, “I want you to take a look at the MBTA. Tell me how good or bad the service is compared to other Mass Transit authorities.” And we did. We turned out to be far more expensive and far less service, and the reasons why. And that turned out to be a terrific story and won the Pulitzer in the early eighties. So, it was terrific. You know, you get time. You don’t have to file on a deadline. And you’re doing stories that have an effect on the community. And that really spoke to me. Doing things the right way. I’m not sneaking around, I’m not breaking in. I’m not stealing documents. I’m using the authority as a journalist that we all have—the first amendment, the freedom of information act and being fair and being thorough and doing data-driven reporting. You can come up with amazing stories that make a difference in our community… The more local you become, the more effective you become in people’s lives. I’m not just talking about the school lunch program. I’m talking about covering the planning board meetings and the Selectmen’s meetings, and the town meetings to figure out in that community what matters and what people are putting their emphasis on. Are they putting their emphasis on more police? Or more teachers? In a democracy, that discussion goes on in every community. If you cover it, you will generate more interest among the public.

***

K.V.: Let’s get back to talking a little bit about the chronology of your career.

S.K.: Surely. There’s an important five or six year period. I went to Washington. And the Globe had some issues with its Washington Bureau and I had a really charmed career in spotlight. I chose my own stories, chose my own reporters, researched it as long as I needed to research it.

K.V.: How long usually did a piece take?

S.K.: Back in the day, I could do a Spotlight piece myself, one piece a month. But having 3 reporters, we could do a series, five to eight articles within three or four months. But we got a lot of play and became sort of a brand. Not as it would become with the clergy abuse and the, you know, academy award-winning—

K.V.: —the movie. In which you were not really accurately portrayed. I re-watched it yesterday. Even I was offended by that, seeing you here in the recording studio, such a cheerful disposition.

S.K.: [Laughs] Thank you, Karine. I could talk about that. The feeling that this was a charmed life, but the Globe said to me, “We need someone to bring management skills to Washington. Would you go to Washington for a few years?” I said, “Terrific.” So I had two wonderful children at the time, a fabulous family. And we uprooted, left Greater Boston and we went to Washington. Very difficult. I had not covered daily journalism for a long time and I had never been a political reporter and I was asked to oversee. But I used my, you know, dint of my hard work, determination and I loved the reporting. Either reporting at the Justice Department, Supreme Court, or the White House. I had eight, nine reporters working under me, with me. And we changed it around. We got the Globe’s brand into the daily newspaper, not just the Sunday newspaper.

K.V.: Did it change your perspective on the way the U.S. government operates?

S.K.: Good question. There always seem to be a middle ground that neither side—even then—didn’t want to get to. I remember that leading up to, in the mid-late eighties, President George Herbert Walker Bush having said at the convention in ‘88, “Over my dead body will we raise taxes.” Well for the next year, the Democrats urged him to change that mode and accept new taxes so we could pay for—I think there was the first Iraq War that was going on—and start funding domestic programs in the environment, in medicine that needed to be funded. And they worked on him and worked on him and worked on him and he finally agreed, finally he consented to the Democrats and the more moderate Republicans. “We’re going to change that. I’m going to go back on that campaign pledge.” There wasn’t a day that the Democrats—who had been urging him to change—hammered him for going back on his promise. They didn’t sort of get together and say, “Thank you, Mr. President.” They didn’t use this concession that he gave to earn a new way forward. They beat up on him.

K.V.: So the reality of the situation gave you more of a bipartisan perspective?

S.K.: Well, it’s a sense that politics is always gonna rule. There’s very little chance for consensus government. The moment that I saw that, I was sort of surprised. They play rough. Politics is not bean bag, is what they’d say, and it wasn’t. But what I missed most about being in Washington—not only not being with my larger family and also the Red Sox and being part of the Boston experience—what I missed was making a difference. I felt we were covering the news and not breaking the news. And I really felt, as an investigative reporter, there was something about breaking news that made a difference. That telling stories that no one else would have gotten. You know, the Washington Post was doing some. The New York Times was not doing enough. We tried to do a little with the drug wars that were going on. But it’s so hard to make a difference at a smaller newspaper. The Globe was renowned for its political work–covered politics terrifically. But I felt that I wanted to be involved with breaking the stories that other people were not breaking.

K.V.: Right, and Boston is really your turf.

S.K.: We’ve got a great fertile field here in this area. So I came back and got back into investigative reporting in the newsroom. Did not get back into Spotlight. I was more interested doing quicker investigative pieces and did a couple. But the big thing that happened in the early nineties, is my sister said to me, “Stephen, our father wants to go back to his home.” And this was the linkage to my recognition of my Armenian-ness.

***

K.V.: Up until that point, you hadn’t really identified with that side?

S.K.: I had not. I really wasn’t connected to the Armenian community. My Armenian family, of course, but not the history of who we were and what we were doing. How did we happen to be here? That light never needed to go on. I always felt very proud of being an Armenian, but not the history. So when my sister said, “Dad wants to go back to his village.”

K.V.: In Turkey? So he was from Western Armenia.

S.K.: He was from Western Armenia from Kghi. And I said to him–my father’s an artist, and he was about 80 years old at the time and he lived for another 10-15 years. He was a terrific artist–commercial artist. And I said, “Dad, do you know what the name of your village was?” And he said, “Ask Aunti Araxi.” She was an older aunt, his father’s sister.

K.V.: He was born there?

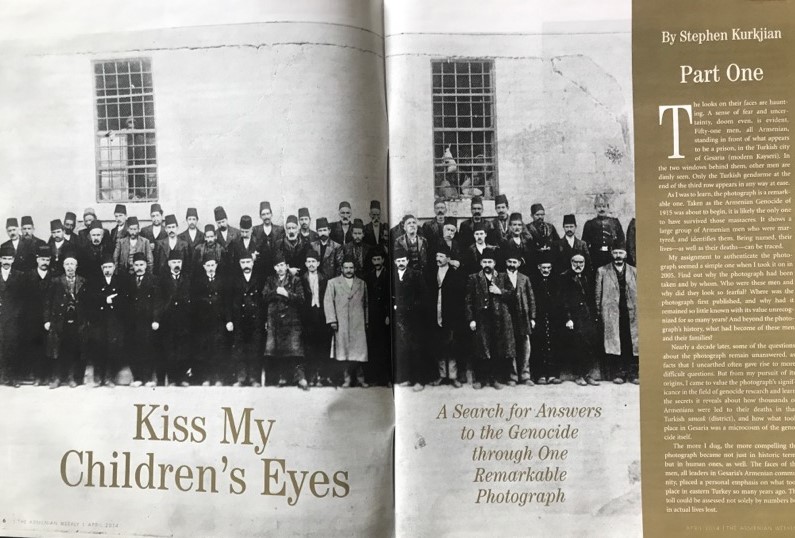

S.K.: He was born there. He survived, but his mother lost her husband. His father was killed in the Genocide. Lost his brother and sister on the trek to safety, 300 miles they were able to travel to Aleppo. So I went to one aunt. She was unable to talk. She was inconsolable, when I said to her, “Auntie, I want to go back to Kghi. Please tell me about your family’s past in the old country.” She began to cry and could not catch her breath. I sat there for 15 minutes while she sobbed. This was ‘92!

K.V.: And as a journalist, you’re thinking, “This is a story.”

She was inconsolable, when I said to her, “Auntie, I want to go back to Kghi. Please tell me about your family’s past in the old country.” She began to cry and could not catch her breath. I sat there for 15 minutes while she sobbed.

S.K.: What have I uncovered? What’s going on? Exactly, Karine. This is a story. So I went to another aunt, and she was like putting on a record. She did not stop talking for two days. She gave me every piece of information, every date, every place where their family had been. So, at least now, I had a blueprint of where to go. And so I reached out to NAASR, the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, and they told me about a man, named Armen Aroyan in California, who had just started a business—he was an engineer—bringing families back to their homeland. And he had done it for one other family earlier in 1992—and he said, “Well, I’m going to bring another family in September. Would you and your father like to come?” So I called my friends at the State Department, and I said, “Is it ok to go to Turkey?” And they said, “No, it’s very dangerous…” And Armen just waved his hands and said, “Don’t listen to them. We’re fine. We’re gonna go.” So my dad and I went for about 15 days with him,and we went to probably 8 different villages, saw the Armenian experience, went to my father’s village. But a light went on in my head as to what I was experiencing here. We were outside one of the villages and we were walking back from a stream and it’s Munjusun, a very small, out of the way Armenian community, where Armenians had lived back in the day, and he pointed to one of the houses, and said, “That was an Armenian’s house.” So I looked at it and I said, “Armen, how do you know that’s an Armenian’s house? Armenians haven’t been here since 1915!” And he says, “The windows. Look at the windows, they’re big, wide windows.” And I thought, “Hey I know those Armenians. Those are the Armenians that open up their windows and shout down from the third floor, ‘Hey Steve, where you goin!’”

K.V.: —in Dorchester.

S.K.: In Dorchester! These are the Armenians who engage, are not afraid of life. They embrace life.

K.V.: Well the Armenians of Boston are a very distinct breed. [Laughs]

S.K.: [Laughs] Exactly, we’re not afraid of anything. We’ve been here for so long.

K.V.: I’ve heard someone once call them the Pilgrim Armenians, they’ve been here for so long.

S.K.: Well, that’s true. My children are second generation. My grandchildren are 3rd generation. But I get on the bus with Armen, and I said, “Armen, I want you to come to the back of the bus and sit with me.” We were going on for another five-hour bus ride to another village. And I said, “I want you to do one thing. I don’t

K.V.: Was it at that point that you started paying more attention to the infrastructure that’s here locally? At what point did you start to tune in to the Armenian press? Because there’s actually a bit of a network of Armenian newspapers in the Boston area—including ours.

S.K.: Surely, the Weekly, the Mirror-Spectator, two terrific newspapers. Well, my grandmother, who was also a survivor, she was from Kharpert. She was a teacher. She had gone to Euphrates College for women. She would read the Baikar. She would read the Armenian press. When I was working nights, I would get up later in the morning and she and I would sit there—me reading the Globe and she reading the Baikar—and we would talk about events going on in the world. She learning it from the Baikar and me learning it from the Globe. So, I got to know the Armenian press, and when I started writing articles, the Mirror-Spectator and the Weekly would sometimes write about stories I had written.

K.V.: Did you start producing stories about Armenian issues for American publications?

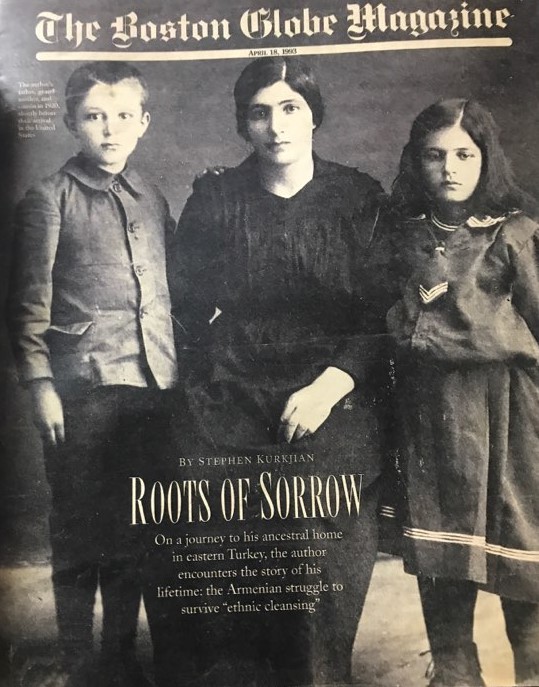

S.K.: No I did not. It wasn’t until that light going on. And so I wrote. I wrote a history of the Armenian people, what we’re doing here, and who we are. Front page of the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine in 1993. Took me about four, five months to do it.

K.V.: At that point, how much had been covered?

S.K.: Nothing. Well, there had been issues regarding the Armenians and we had begun to ask for recognition, ask for coverage in parades, or demonstrations, or protests. April 24 events at the Statehouse had already started, but we weren’t getting that much press. And people knew us as neighbors more than they knew our history. We had been here such a long time and we had not been proclaiming our history or what we were doing here for most of that time. Only in 1965 did we become politically…

K.V.: Loud.

S.K.: Loud. Right. But from what I could see, nothing had contained our full history and that’s what I wanted my Sunday story to do and I wanted to personalize it through my father’s experience. He saying, “I want to go back because I wanna see where I grew up so I could sketch it.” So we went back, and not only did he see his village, but I found my history, and it was breathtaking. And it continues to be breathtaking to me as far as how it happened that this small tribe of unimportant people became perhaps the most successful immigrant group in America.

***

K.V.: So what was your involvement with the Spotlight team? Can you just talk about that?

S.K.: In that series itself? Well I had been, in the early nineties, one of the areas that I got assigned to was clergy abuse and I—

K.V.: It was already being covered by the Globe as early as the nineties?

S.K.: It was a case involving Father James Porter and he had been accused of harming, abusing several kids, maybe a dozen in Fall River, which was part of the Archdiocese. They have their own diocese, but it fell under the Boston as well. So they asked, “Steve, could you get on this and catch us up?” So I did. And it just seemed to me that this could not just be a problem with just one priest. The more I looked back in it, I found that elsewhere, if there was one priest caught in a parish, there were other priests in that parish that were doing bad things. So I caught us up, we did good work on Porter. But I started finding there were another couple of priests in the Worcester area and I got a call from a fellow who was an advocate, had been abused by a priest out there. And he told me about his experiences. So we got that priest. And we put it in the paper. It always seemed to me that we were doing really important work that no one knew about. And every time I found another priest–and we did about three or four at the time–it seemed that two things happened. One was that the church–when I went to the Archdiocese, Cardinal Law here—he would feign such surprise and pain that another priest had done bad things to the kids and we’re going to provide solace and comfort and counseling to the kids. And if we do find that there was hard, we’re going to remunerate them, give them settlements. He also angrily called down the wrath of God on the media, including the Boston Globe on a Saturday speech he gave. He was so upset.

K.V.: Do you think that has something to do with… I find in community journalism, especially through my experience, when you’re working in a tight knit community. You’re going to offend people eventually. Was there that sense of a fine line between community and objectivity?

What’s going on that good men, involved in a profession of generosity, fellowship, fidelity—would do bad things? Why?

S.K.: Not really because the Globe always realized it was a newspaper first. It was a member of the community, but it was enterprising and, you know, if the Globe is on it, it’s a story. But there was a sensitivity to it, but no one would ever say, “Steve, go easy on it. It’s embarrassing to our community and our community is predominantly Catholic.” There was never that sense. But I ran out of tips. I probably got three or four in the paper, but I ran out of them. And what I learned had happened is that the Archdiocese had put in a new procedure. And that procedure, because of our reporting, had told the attorneys for these kids that had been abused, “Come in, and we’ll give you settlements. But with that settlement, you cannot make public your claims of abuse, and you cannot go to the police.” So our reporting that we did sort of got shut down by this new procedure that the church had put into effect. And a lot of cases got dealt with between the kids who had been abused, the lawyers they went to, and the Archdiocese. Until one lawyer said, “We’re not taking any settlement.” And that was Mitchell

Garabedian. Another Armenian. And he said, “No. There is a major scandal here. And we’re not going to take their blood money. If a person wants to make a settlement, I’ll send them to another lawyer. We are going to sue the church for this conspiracy.” And he was, you know… I may not have gotten full recognition, and I’ll tell you another thing about the Spotlight movie that bothered me immensely, but there were two heroes it seems to me in that whole thing. One was Mitchell Garabedian, and one was the editor of the Globe, Marty Baron. And Marty Baron had just come to Boston from Florida, he had been the editor of the Miami Herald. And everything is public record in Miami. And he said, “Listen, this Garabedian is suing the church, but the court has closed the records, so we can’t get to the bottom line here. Why don’t we sue to get those records open?” And we began reporting on the lawsuit in trying to get what was going on with this Father Geoghan. It took six months to get it into the paper in 2002, but it was only because Baron had said to the Spotlight team, “Go after that, go after that. Just get to the bottom of it. Why is the church sealing the records on this court case? Court cases are always open. Yet here, the court has sealed these records to conceal the embarrassment that was obviously in those paperworks.” And that’s what the Spotlight team got on, and when they broke the story in 2002, there were dozens more people calling—family members of kids, who had even gotten settlements–but called the Globe and said, “Listen, it’s not just Geoghan. There are other priests, too.” And each of those priests had been called in, had done bad things to kids, those calls to the Archdiocese had led to the church settling those cases. Nothing was on the public record. There were no court cases. But there was no way of getting the details of how big, how extensive the scandal was, unless you did interviewing. And that’s why they brought me back down to Spotlight. My third Pulitzer was on clergy abuse. I came back and they said, “Can you follow up on some of these cases to see if we can get confirmation?” Because the kids, who were now adults, were calling in and saying, “I’d been abused, I’d been abused, I’d been abused.” So one I looked at and I said, “This priest, he’s now living in a private home in Arlington, I should be able to get him to confess.”

K.V.: And this is the part in the movie that was actually played by—

S.K.: Rachel McAdams. [Laughs] I look good as Rachel McAdams.

K.V.: She took this scene, actually. So let’s set the record straight.

S.K.: But that’s an important scene and I was upset that they gave… this was not happenstance. As it shows in the movie, it’s almost like happenstance. She just knocks on the door and he comes out and she asks him a question. It wasn’t that easy.

K.V.: What happened?

S.K.: Thank you. That’s a good question. I had been sitting in my car waiting for him to come home on a Friday afternoon and I had been sitting in my car waiting for him to come home on a Friday afternoon and I was listening to the radio and former Mayor Ray Flynn, who was an ardent Catholic, a good man, had just come back from the Vatican as an ambassador to the Vatican, he was on the radio and he was talking about the Geoghan story that had been in the paper two weeks before. And he says, “You know, I know the Globe is going crazy with one priest or another, but it’s a very small number of priests involved.” But I knew the calls we were getting to Spotlight after the Geoghan story, there were dozens! I knew there was a pervasive problem here. So I said, “I have to get this man to admit. But he has to tell me why a priest would abuse.” It always seemed to me to be, and it still is—what’s going on that good men, involved in a profession of generosity, fellowship, fidelity—would do bad things? Why? And so he walked up to the steps, he came down, I saw him, I walked up behind him and I said, “Father Paquin, this is Steve Kurkjian from the Globe. I need to talk to you.” And he says, “No, I have nothing to say.” And I says, “Father Paquin, I’m not sure why you were accused, but I know this thing is never going to end unless people who are involved in it speak up publicly and tell us why? Why would you have abused, molested young men, young boys, alter boys in your parish? Tell me why did this happen?” And he said, “You wanna know why?” And I said, “Yes, I do.” Because it’s not going to end until people who are caught up in the scandal speak about it publicly. And he said, “Okay, I’ll tell you.” And he brought me into his house and he brought out his big file folder and he showed me that he himself had been abused as a kid. And he had somehow pscyhologically fallen into this cycle of abuse. And he said, “I have been abused by a priest. I abused, too. But I’ll tell you one thing. I didn’t gain pleasure. I gave pleasure…”—ridiculous stuff.

K.V.: Perverse logic.

S.K.: Perverse logic. So I said, “I appreciate that.” And I put that in the paper and he later was prosecuted and spent a lot of time in jail. As so many of them have.

K.V.: Did that change the way you were seeing the world?

S.K.: No, it didn’t, I mean… My mother called up and said, “Stephen, you should have told me you were interested in this.” I said, “Why, mom?” Growing up in a predominantly Catholic Dorchester neighborhood, we had one major building, one edifice, grand edifice, and that was a Catholic church half a mile away. And my uncle, older uncle, her brother, was a kiddo in the thirties, and he would go up to the church, and she would say to him, “Krikor”—Gregory—”Krikor! Did you go in? What’s it like inside the church?” Because we’re going to our clapboard Armenian church. [Laughs] So he says, “No, I don’t go in there, Rosella.” And she said, “Why? Why don’t you go in?” “The priest. He pulls your pants down.” And she remembered that quote. This is now sixty years later. And she said, “I can’t believe it,” she said, “Stephen, this has been going on for a long time.”

***

K.V.: Given your impressive career in local Boston journalism, how do you view the homegrown Armenian newspapers in the area?

S.K.: I think they have a very important role. But. All the institutions are changing. As the Globe is changing. As the Armenian organizations are changing. The Armenian newspapers are changing. By that I mean, their connection to the younger generation. For me it was later than it should have been. I should have been a more active member, a more involved member, a more aware—awoke member? (Ha!) Shame on me for that. But all young Armenians need to be aware of their heritage and their history and their narrative.

K.V.: Right, but isn’t there a trap of newspapers becoming these documents of the past, as opposed to documenting the present?

S.K.: You’re the editor. You’re the one who decides what gets assigned.

K.V.: [Laughs] The former editor.

S.K.: Former editor. You get to decide what’s important.

K.V.: Do you think editors are making the right decisions right now?

S.K.: I think that what you have to do is try to figure that out. What does your community want? What is your younger community looking for? And how to engage them? You know, they are becoming Americans. So, what you’ve got to make them feel is how to hold onto their Armenian-ness. And there’s a way. And that’s our heroic history… But understand, you’re challenging yourself with a question. And that’s a good thing. That’s what we’re supposed to be doing as journalists, trying to figure out why has this happened and trying to figure out how to build a bridge to make sure that there’s a need that gets met. You’re not going to run a full page of American news articles, but how it relates to Armenians in Armenia, how American decision-making relates to Armenians here? That’s an important part of what we should be covering.

K.V.: Right. And so what’s your latest project that you’re working on?

S.K.: Thank you. I’m working on two. One is a narrative about the lives of two of my cousins, both accomplished pianists. One became renowned, helped teach Yo-Yo Ma. And her cousin, she had a mental condition and she had to give up the piano. These women were born both in the early twenties, yet by early thirties, they were performing in front of thousands of people. How was it that their families were able to bring up such geniuses? I think it has something to do with the families, but it also has something to do with the community here in Watertown, just a couple of blocks away from where your newspaper is. You know, they were all survivors, or children of survivors, people who had just survived. They weren’t talking about what had happened, but they were able to bring up their kids to be right away, feel protected and achieve their fullest. So that’s one. And the other one is, last month, Alabama became the 49th state in the Union to recognize the Genocide. As we know, there are 50 states in the Union. 49 of the 50 have adopted in the past three or four decades…

K.V.: Mississippi’s the only one that’s remaining.

S.K.: Exactly. And so I wanted to stop traffic. My newspaper, journalism experience, my bells go off, and when I saw that, I said, “Wait, wait. Forty-nine out of fifty, I knew there were a lot, but I had no idea…

K.V.: It’s a national story if there ever was one.

S.K.: It’s a national story. Absolutely. And so I want to understand how it happened, who were the people who did it, and how did they do it? And as I’ve found is that this is an American record. American historical record shows there was a Genocide. Whether it’s Wilson administration, the State Department, Morgenthau’s telegrams. The Turks can fuss and fume, but it’s an American historical record that’s being recognized here. And it’s to our favor.

I thoroughly enjoyed this conversation. I particularly appreciated Stephen opening up about his early career and about his (re)discovery of his Armenian roots–it was heartfelt and honest. Hats off to Karine and the Armenian Weekly for producing such high-quality content and for continuing the paper’s seamless transition into the digital world. Ապրի՛ք…

crushing load on a small culture with a huge brain of experience to expose the Turk who thinks they are Genghis Khan entitled to conquer.Other cultures are guilty if not more than the Turk for insular ” its not in our interest ” state of mind which is commercial of course but adds to the comfortable state of ignorance. So what do we do people of Armenian culture (David vs Goliath )

Steve Kurkjian is one of the most thoughtful, yet persistent reporters I ever met either while I was a member of the media or handling communications for public agencies. So glad to read this background on his amazing career, and especially proud that he never forgot where he came from, culturally and geographically. He reminds me of one of my favorite people in politics, the wonderful late Peter Torigian of Peabody.

What an extraordinary life and career! Thank you so much for this interview. Mr. Kurkjian is an inspiration to us all.