When her daughter Areni was just a year old, Taline Badrikian vividly remembers watching her on the baby monitor, just sitting in her room flipping through books by herself for 30 minutes at a time. Unfortunately for Badrikian, whose first language was Armenian, most of those books were not written in her native tongue. And when they were, they were rare and paperback—certainly not durable enough for the darling, but unpredictable hands of her toddler.

When her daughter Areni was just a year old, Taline Badrikian vividly remembers watching her on the baby monitor, just sitting in her room flipping through books by herself for 30 minutes at a time. Unfortunately for Badrikian, whose first language was Armenian, most of those books were not written in her native tongue. And when they were, they were rare and paperback—certainly not durable enough for the darling, but unpredictable hands of her toddler.

Dismayed by the absence of Armenian language resources for children, the now busy mother of two, whose day job is in marketing, started an unexpected project back in 2016—writing a Western Armenian children’s board book. “I’m not a writer. It’s not what I do. I never considered myself the type of person to go out and write books. But I want [our children] to know how to speak, read and write [Armenian].”

Badrikian admits retaining Armenian at home is challenging since it’s not the exclusive language—a common denominator among countless other Diaspora families in the United States. “Even parents who are Armenian don’t read [the language] as well as they would like,” said Badrikian. This was one of her motivations behind utilizing transliterations—pronunciations of Armenian words written out in Latin letters. Parents may not be fluent in reading Armenian characters, she explained, “but I didn’t want that to be the reason their children are not read to in Armenian.”

So she went to a Boston coffee shop one day (The Thinking Cup, ironically enough) and cranked out a story. “What are some of the kinds of lessons I want to teach my daughter regardless of language?” explained Badrikian of the storyline. “What are some messages that I want to ingrain in her from a very young age so that she doesn’t question them down the line?” The book, sweetly named Oorakh Khozooguh (or, The Happy Piggy), is about a little pig who likes to get muddy. In the end, his friends learn to accept him for who he is—a modern day life lesson that even adults can appreciate.

Oorakh Khozooguh (2016) was the first installment of Badrikian’s Kids Reading Armenian series; it quickly became a wildly popular book in the local community, thanks, in part, to an equally successful Kickstarter campaign. Badrikian raised over six-thousand dollars—enough money to fund a second book and then some. “They see a need,” she explained, reflecting on the overwhelming support. “But even if they don’t see a need, they’re willing to support a cause that I think is for the betterment of the community.”

Badrikian—a first generation Armenian American—says she has the fondest memories of growing up in this local community. She attended Armenian Sisters Academy in Lexington and St. Stephen’s Saturday School in Watertown; then she joined Homenetmen scouts and the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF), where she says she felt the most unique sense of responsibility. “It’s the one organization that I credit with giving me the confidence and the self-awareness about my capabilities.”

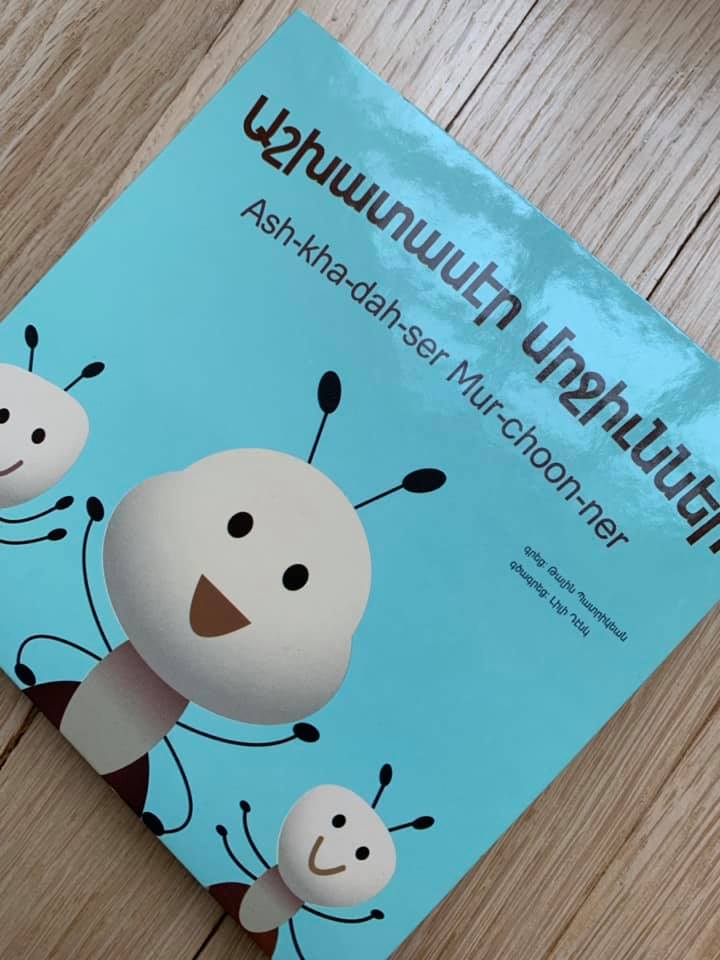

Community happens to be a theme that resonates throughout Badrikian’s latest book, Ashkhadaser Murchooner (“Diligent Ants”). This one is about teamwork and the idea of leaning on each other. Like their barnyard animal friend, Ashkhadaser Murchooner is meant for small children, ages 1-5, who have big ideas. “[Ants] are the hardest workers, and people underestimate them. They’re better in teams, and they accomplish a lot for their size and for what they’re doing.” Badrikian’s books are guiding Armenian children in the Greater Boston community and beyond to learn these relevant messages during the most prime time for establishing a sense of awareness and belonging.

Community happens to be a theme that resonates throughout Badrikian’s latest book, Ashkhadaser Murchooner (“Diligent Ants”). This one is about teamwork and the idea of leaning on each other. Like their barnyard animal friend, Ashkhadaser Murchooner is meant for small children, ages 1-5, who have big ideas. “[Ants] are the hardest workers, and people underestimate them. They’re better in teams, and they accomplish a lot for their size and for what they’re doing.” Badrikian’s books are guiding Armenian children in the Greater Boston community and beyond to learn these relevant messages during the most prime time for establishing a sense of awareness and belonging.

Ashkhadaser Murchooner has been part of my three year old’s bedtime book rotation for several weeks now. Readers will instantly realize that Badrikian’s use of the Armenian language is conversational and basic for her intended age group. The illustrations are colorful and simple but detailed, right down to the sweat drops breaking from the ants’ foreheads as they lift a leaf together. Underneath the Armenian text, the reader will find a phonetic English transliteration, which promotes the recognition of the Armenian alphabet relative to the sounds each letter would make. There’s also a critical rhythm to Badrikian’s books, which you could say she models after her favorite children’s book author, Sandra Boynton. (The Going to Bed Book signals the start of bedtime in the Badrikian household. The family knows the book by heart now.)

As many [Armenian] books as I can put in front of [our children], I will.

Without a doubt, there is a great need for people like Badrikian, who is part of a growing community of new authors of Western Armenian books, which includes artist, author and St. Stephen’s Armenian Elementary kindergarten teacher Alik Arzoumanian, also recently profiled in the Weekly. These creative efforts facilitate the preservation of an increasingly endangered language, providing important resources for the youngest members of the Diaspora.

But Badrikian says parents also have a great responsibility. “The best thing we can do is practice the language to keep it. It’s just all about introduction and ingraining it and making it a natural part of their day to day. Hopefully it will be sustained. It’s up to us to make sure it does.”

Little Areni is now four years old. During visits to the children’s section of the Watertown Public Library with her maternal grandmother, she has made a charming habit of looking for her mother’s children’s book—Oorakh Khozooguh—on the shelves. She has even checked it out of the library a time or two. “Every third occasion that I’ve gone there [to work],” laughed her mother, “I go to look for it, and it’s never there.”

Badrikian must be doing something right. “As many [Armenian] books as I can put in front of [our children], I will.”

You can do the same by adding Badrikian’s books to your child’s at-home library here.

Be the first to comment