When your country’s Prime Minister is the former CEO of one of the largest gas corporations in the world, it often feels like what should be a government’s responsibility to protect natural resources has steadily become yet another conflict of interest. The rhetoric of rapid economic growth consistently outweighs sober assessments of long-term sustainable investments and development and as a result, environmentally sound and socially ethical alternatives to extractive industries, like mining, which are rampant in Armenia, rarely get the attention they deserve in the media.

However, though they are rarely cited, there are local communities in Armenia who are rising up against mining, and stand firm in their belief that only a long-term plan that is in balance with nature is worth investing in—even if it doesn’t promise rapid accumulation of wealth. This article features one village, in the hilly valleys of Armenia’s Vayots Dzor region, that has chosen conservation over exploitation, and suggests that a second village in Lori might be close behind.

The Curious Case of Vardahovit

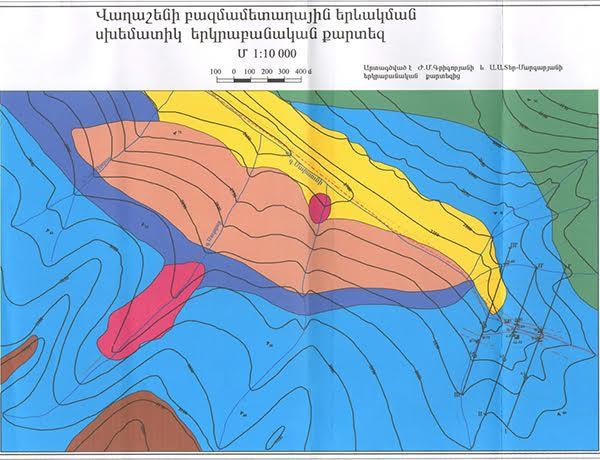

In 2016, the community of Vardahovit, located in the fertile and biologically diverse Vayots Dzor region of Armenia, learned about a mining company’s search for metals in their and nearby communities. The company was performing geophysical prospecting in the area, looking for gold, copper, zinc, lead, selenium, bismuth, and germanium, all within the areas of five communities in Vayots Dzor. The geo-prospecting works were to be carried out in Vardahovit, Yeghegis, Hermon, Horbategh, and Goghtanik communities.

“They knew they didn’t want such a project polluting their environment. So they turned to us for cooperation,” explains deputy director of the non-profit Foundation for the Preservation of Wildlife and Cultural Assets (FPWC), Eva Martirosyan.

In 2012, the FPWC had become member of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is the world’s largest and most diverse environmental network dedicated to fostering conservation practices internationally. Whereas before, conservation operations in Armenia were conducted primarily through the state, FPWC has brought a new culture of conservation to Armenia, now employing privately protected areas. While the shift to civil society and the private sector raises questions about state’s commitment to its environmental responsibilities, this particular development has been a valuable tool for the people of Vardahovit.

FPWC had already been operating in Vayots Dzor since 2016, as it is an an important migration area for animals according to Martirosyan, so when the community of Vardahovit approached them in 2017, they were happy to help the community find an economic and environmental alternative to mining. Vardahovit decided to lend their lands to the nature conservation organization, which—in addition to environmental protection—would also work on its long-term development.

“When cooperating with a community, we concentrate not only on environmental education, conservation, but also on investing in the sustainable development of that community,” says Martirosyan. “As such we pay attention to two main components—alternative energy and water infrastructures. For example, the installation of solar heating systems on community buildings reduces the energy costs of the community budget by 70 to 80 percent which is then spent on educational projects. We also invest our efforts in establishing or improving drinking or irrigation systems in a community. Renting community lands is yet another area of our work which is done for nature conservation and possible development of the communities.”

Martirosyan highlights that renting community lands has several goals aside from nature conservation. Where viable, lands are allocated for sustainable farming for community residents. If in the past the residents had to pay for cattle grazing, now they can do it for free in the lands allocated in the privately protected areas. Yet, for the purpose of species’ habitat protection, not all lands can be used for that purpose. Moreover, renting community lands for conservation purposes also provides sustainable income to the community budget. “While we might pay less than a mining company for renting the lands, we provide a long-term income to the community’s budget,” Martirosyan explains. “In fact, we rent only some of the lands since others are even given by the community for free for our conservation purposes.”

Martirosyan adds that hearing about their activities and how the organization makes efforts to combine nature protection with ecologically friendly activities such as organic farming and eco-tourism, other communities have started approaching the organization for cooperation prospects.

A Solution for Other Villages?

The experience of Vardahovit was recently considered by another at-risk community, located to the north in the Lori region.

Residents of Ardvi village were among those few communities in Armenia who expressed their opposition to yet another mining company, which planned to carry out geological studies in the hills of Ardvi. In this case, the village residents opposed the project right from the start, expressing their opposition by re-filling holes dug by mining company experts and preventing public hearings.

“These hills are the source of drinking water to us. The company promised to build water infrastructure for us, but why build an infrastructure if you are going to spoil the water sources?” says Ardvi resident Suren Kirakosyan.

The community residents have a different perspective for the development of their village. They see potential in tourism. “We not only have old architectural complexes in and near our village, but also, the nature here is amazing for hiking activities. Furthermore, we are looking forward to reviving some really old celebrations that would increase the flow of local and international tourists. We have many thoughts and plans that we look forward to implement with those who can invest in eco-friendly industry,” says Kirakosyan.

In fact, the community already took the first step in this direction and organized a New Year’s celebration, following some of the old Armenian traditions and ceremonies. The community is firm in its decision and sees only long-term sustainable development as an acceptable investment.

Communication with Suren also reveals the struggle of Gladzor—another community in Vayots Dzor—against mining plans in their community.

Only when communities themselves weigh the short-term gains versus long-term losses, can a joint effort with environmentalists truly be effective.

This information was useful to me