Hachig Kazarian’s new book a must-read for Western Armenian music lovers

Western Armenian Music: From Asia Minor to the United States

By Hachig Kazarian

Published by The Press at Fresno State University

Publication date: 2023

Hachig Kazarian has penned a wonderful book, Western Armenian Music: From Asia Minor to the United States. It is the 18th book in Fresno State’s Armenian Series, first edited by Dikran Kouymjian (1986-2008) and then by Barlow Der Mugrdechian since Kouymjian’s retirement.

Most of us know of Hachig Kazarian. How could we not? He is known for his masterful clarinet playing at Armenian gatherings all around the United States since the 1960s. He is arguably the best there ever was in this country – the GOAT in modern parlance. We know him from the many albums he has recorded, from Passport East with the Hye Tone band in Detroit to the series of Kef Time albums with Buddy Sarkisian and Richard Hagopian. His iconic album, in my view, is The Exciting Sounds of Hachig Kazarian, featuring “Govand.” This one track inspired countless numbers of young Armenians of my generation to take up the clarinet. Some have gotten pretty darn good themselves, but Hachig is still in a class by himself.

This is Hachig’s first book. The 500-page book is in part a scholarly treatment of Western Armenian music and in part a memoir of his years performing.

The book is divided into six sections: The Quandary of Western Armenian Music (chapters 1-4), The Understanding of Western Armenian Music and Dance (chapters 5-9), The Plight of Western Armenian Music (chapters 10-11), Traditional Western Armenian Bands in the United States (chapter 12), Armenian Village Folk Dance Melodies (chapter 13) and Musicological Developments in Armenian Musical Notation and Understanding the Armenian Modal System (chapters 14-15).

Hachig stakes out a place for Western Armenian music in a way that many of its musicians see it. It is its own genre worthy of being celebrated and preserved. After the Genocide, Beirut became a de facto center for Western Armenian culture. Its intelligentsia led a movement to rid the language of Turkish words. In their zeal to define what is purely Armenian, they also stripped folk music of the modal tones that made the music sound “oriental” or Turkish.

Gomidas Vartabed, thankfully, captured and wrote down many of the melodies, songs and dances of Western Armenia. As a people, we have deified Gomidas. Another prominent Armenian ethnomusicologist once told me that Gomidas preserved the modal elements in his work, but others have cleansed the modal elements. “Kele-Kele” and “Groong” are often performed by operatic singers accompanied by orchestras or pianists. It is the purification of what villagers might have sung in the fields or after a hard day’s labor around the hearth. Both are worthy, but the core should not be lost forever, in favor of the concert hall.

The Beirut Armenians preserved and cleansed the Western Armenian language and thought they were doing the same for music. In reality, they faced the West, and that view defined the evolution of Armenian music in Beirut. In the U.S., it was harder to preserve the language, so music was another way of staying tethered to our rich culture.

Armenians started coming to the U.S. after the Hamidian massacres, and the bulk of Armenians came after 1915. For the most part, Armenians migrated to the U.S. from villages. When they gathered in getrons (centers), clubs and churches, they brought their foods, dialects, customs, music and dances with them. The dances, music and melodies of Van were preserved in Detroit, where large numbers of Vanetsis lived. Hachig’s grandfather, for whom he is named, was an expert in these dances and melodies and made sure his grandson knew the music that they brought from “the old country.” As Beirut turned westward, we in the U.S. turned eastward, trying to capture, preserve and build upon the music and dances that our parents or grandparents brought with them.

As Hachig notes in his chapter on Gomidas: “Unfortunately, village folk music was already alien to the wealthy elite Armenians who didn’t like, and looked down upon, village music. Gomidas and his compositions were revered by the Armenians in Constantinople who loved his art songs and choral arrangements as the only true form of Armenian music. Without realizing it, Gomidas’ new polyphonic selections seemed to debase the existing monophonic village folk music that had survived for centuries.”

It may be uncomfortable for some to read any criticism of Gomidas. But Hachig makes a case that all of us should consider. In discussing the cultural appropriation of Western Armenian music and dance, he argues that this music is ours, and we have to embrace and preserve it. It is not just Armenian American, or deghatsi, music, but Western Armenian village music. This music overlaps greatly with kef music, which tends to include Turkish and other Middle Eastern music. Yet Hachig is referring to the village songs and dances of Western Armenia, occupied by Turkey.

Assuming we can all agree on preserving and promoting the village music of Western Armenia, there is still the question of the “oriental” sound. Should we purify it and strip out those pesky microtones to make it more Western? Hachig argues against this. The Armenian modal system is rooted in the sharagans of the Badarak.

As Hachig notes: “In the strictest definition, the modal systems of Armenian folk and sacred music are derived from melody types that are collectively referred to as Octoechoes… The Ut Tsayn (meaning eight tone) system, also referred to as Octoechoes when used by the Armenian church, was created by Stepanos Siunetzi (685-735).”

This modal system is not uniquely Armenian. It is regional and shared by Persians, Greeks, Arabs, Jews, and yes, the Turks, who adopted it when they conquered the region. We should embrace this modal system as well as the polyphonic that is so often used in Armenian popular, sacred and classical music these days. It makes no sense to exclude parts of our culture. It makes even less sense when others are appropriating it and calling it their own.

Hachig also explores the musical notation system created by Armenians over the years. The khaz system was established in the seventh century using letters and symbols. In the early 1800s, Hampartsoum Limonjian developed an even better system. His “Hampartsoun nota” became the standard until the 1920s, when Western staff notation became dominant in both Armenian sacred and Turkish classical music. Hampartsoum nota was important to “preserve and unify the melodies and style of Armenian sacred and folk music. It was the leading contributing factor to the preservation of Turkish classical and folk music.” Before reading Hachig’s explanation of Hampartsoum nota, it looked like a cross between Arabic script and Braille to me. After reading his explanation, I felt I could actually learn it.

Chapter 12 may be the most interesting chapter in the book for fans of Western Armenian music. Hachig writes about the bands started in the 1940s by the children of first-generation Armenian immigrants. Hachig admired or performed with these bands, and their members are his contemporaries. They include: The Artie Barsamian Orchestra of Boston, The Nor-Ikes Band of New York City, The Vosbikian Band of Philadelphia, The Aramite Band of Worcester, The Arax Band of Detroit, The Hye-Tones Band of Detroit, The Kef Time Band, The New Jersey Orientals, The El Jazaire “Night Club Band,” The Arax Band of New Jersey/NYC and The All-Star Band.

In Chapter 13, Hachig provides musical notation for 129 folk-dance melodies of the villages of Western Armenia. We owe Hachig a thank you for doing this.

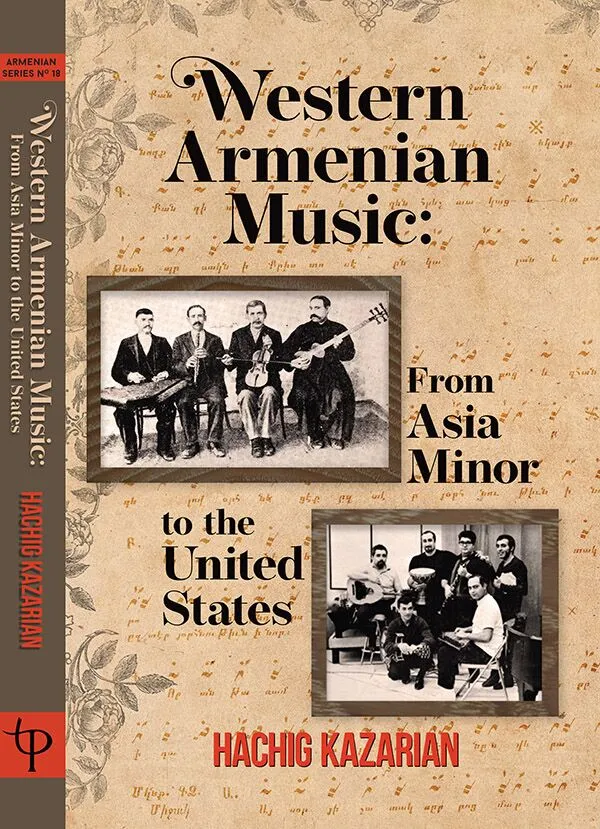

The book is full of photos of bands, musicians, 78 rpm labels, album covers and both Western and Hampartsoum musical notation. The importance of capturing the history of Western Armenian music is evident in two photos of first-generation bands in Detroit. In photos of the Dertad Toukhoian band in 1953 and the Yervant Gerjekian band in 1949, the last names of some of the musicians are no longer known.

Hachig was born and raised in Detroit. He played a clarinet his father had come across in his first workplace at an early age and began lessons in the fourth grade. His grandfather’s friend, Haig Krikorian, was visiting one day, heard young Hachig practicing and offered to teach him Armenian music.

Hachig graduated with bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Julliard from 1960-66. In New York, he met and performed with many Armenian musicians. He writes, “My goal was to be an orchestral clarinetist. However, during my junior year of college, loving Armenian and Middle Eastern music so much, I decided to be close to the Armenian community and have an Armenian family.”

He returned to Detroit, earned degrees in Music Education and Music History and Ethnomusicology from Eastern Michigan University, and began a career teaching middle and high school students. He married his Detroit AYF sweetheart, Christine née Aranosian, and they created a beautiful Armenian family. He moved to Las Vegas for the last segment of his teaching career and returned to Detroit several years ago. Sadly, Christine passed away in October 2023, just as this book was being published.

This book is encyclopedic. It covers a vast array of topics, including the origins of the music of the Armenian national anthem. It is an important resource for historians and ethnomusicologists. It also has a wide appeal for anyone interested in any and all things Armenian. It is a must read for anyone who loves Western Armenian village music.

There are a few things I wish were more extensive. First and foremost, I think the book needs a more detailed index. Fresno State Press might have insisted and helped in this regard. Secondly, in the preface a companion website is provided, westernarmenianmusic.com, where “all musical examples may be heard.” I was excited and expected to find all 129 of the pieces from Chapter 13 to be there. There are only 10 songs on the website, including an old 78 recording of Mer Hairenik. I am sure there are talented musicians in our community who would love to help Hachig record tracks for this website or maybe for a companion YouTube channel.

This is a very important book. It belongs on the bookshelf of any Armenian with a library of Armenian books. I hope it inspires more scholarship on Western Armenian village music and how it has survived and evolved in the United States. We owe Hachig a huge thank you for writing it.

You can purchase the book from westernarmenianmusic.com, Abril Bookstore, NAASR or Amazon.

Hachig will conduct an online presentation about his book, “Western Armenian Music: An Artist’s Perspective,” on Saturday, March 9 at 2 p.m. EST/11 a.m. PST, presented by the Fresno State Armenian Studies Program and the Leon S. Peters Fund. Register here for the Zoom link, or you may watch on the Armenian Studies YouTube channel.

I would like two of Hachig’s books and possibly have them inscribed by the author. Would be great to hear from Hachig himself. My address: 426 South Milton Dr. Yardley PA 19067

I am in the midst of reading Hachig Kazarian’s most thorough explanation of the music my grandparents and many others brought to America from historic Armenia. Up to now, my defense of playing this music was that it was preserved by those who experienced the effects of the genocide and was part of our culture. Now we have definitive proof that this is Armenian music. I want to mention to Hachig that Robert Haroutunian, of NY, has produced 2 DVD recordings of the village dances. They are at the Library of Congress and are titled “A Trip to Historic Armenia Through Dance”.