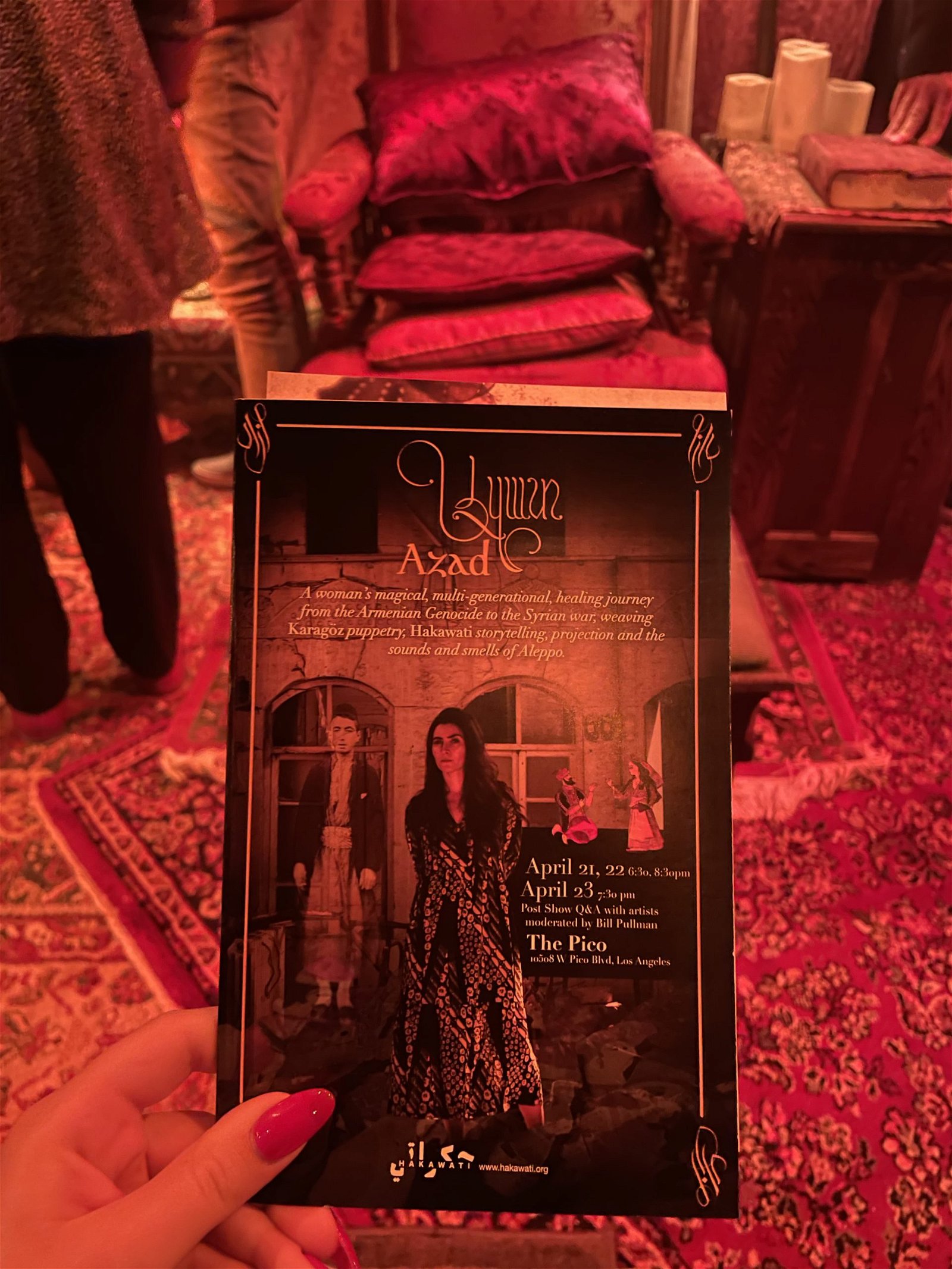

This past week, I attended a performance of Azad, starring writer, performer and co-director Sona Tatoyan, and I can confidently say that I left the playhouse a changed person. Entering the Pico Playhouse lobby for the showing, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect, as I had a loose idea of the performance. From what I read online, it was a blend of the classical art of oral Middle-Eastern storytelling, the ancient artform of Anatolian Karagöz shadow puppets and the beauty of modern cinema. I flipped through the program I was handed for a moment, then decided to take my seat. What I didn’t know then that I know now is that Azad forever altered my mindset.

This past week, I attended a performance of Azad, starring writer, performer and co-director Sona Tatoyan, and I can confidently say that I left the playhouse a changed person. Entering the Pico Playhouse lobby for the showing, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect, as I had a loose idea of the performance. From what I read online, it was a blend of the classical art of oral Middle-Eastern storytelling, the ancient artform of Anatolian Karagöz shadow puppets and the beauty of modern cinema. I flipped through the program I was handed for a moment, then decided to take my seat. What I didn’t know then that I know now is that Azad forever altered my mindset.

Walking through the doors of the black box theater, I was greeted with an ambrosial smell reminiscent of my visit to a church in Lebanon. I could not identify why I immediately thought of the church nor could I pinpoint the fragrance notes, but possibly a mix of amber, jasmine, sandalwood, incense, oudh? I couldn’t quite put my finger on it. Nevertheless, and for whatever reason, it smelled like home.

As I continued my walk to my seat in the intimate theater, ornate Armenian rugs were skillfully sprawled on the floor, lit candles brightened up the room, and in the distant corner, Middle-Eastern melodies filled the air through the hands of a man playing an oud, who I later learned was Dimitris Mahlis. I was beyond dazzled at the attention to detail.

I opened the program once more. In addition to Tatoyan and Mahlis, the team that was able to execute this feat includes co-director Jeremy Boxer, Karagöz puppeteer Ahmad Sayeed, musician and sound designer KÁRYYN, Aleppo producer Antoine Makdis, executive producer Ahmad Zahra and associate producer Garo Kharadjian.

And then, it began.

Azad (meaning “free” in Armenian) is “a kaleidoscopic story within a story within a story,” taking audience members from a Middle Eastern coffee shop during the Ottoman era to a pre-civil war Aleppo. It follows Tatoyan’s discovery of her great-great-grandfather’s shadow puppets, which she located a century after the Armenian Genocide in the attic of her family home in Aleppo, Syria.

Her great-great-grandfather was a skilled storyteller (Hakawati) whose chosen artform was Karagöz, an ancient, Anatolian form of pre-cinema that plays with the relationship of shadow and light. As Tatoyan describes it, it is an “alchemist of imagination.” More than that, it allowed for storytellers – like her great-great-grandfather – to “speak the unspeakable,” criticizing the uncriticizable in a time where doing so could get you killed.

This journey leads our storyteller to discover One Thousand and One Nights, the only book she brought on her trip to Aleppo. In the frame story of the novel, the audience hears the famed Middle Eastern folktale that follows a king named Shahryar who discovers that his wife is being unfaithful. This unimaginable pain leads the king to believe that all women are the same, deciding that he will take a new bride each evening and kill her the next morning. A specific character that sticks out is ScherAzad , the daughter of the vizier, who begs her father to offer her up as the king’s next bride. The astute ScherAzad begins to weave magical tales every evening, leaving the story at the most suspenseful, heightened moment, a moment the king wants to know all about. ScherAzad says that she will continue the story…the following morning. She does this for 1,001 nights. During this time, King Shahryar falls in love with ScherAzad, the woman who healed him through the power of storytelling.

“They were moral tales exploring all the shades of the human condition…our capacity for transformation,” says Tatoyan. “The framed story of One Thousand and One Nights is a story of healing trauma.”

A seamless blend of all categories of artistry, Azad utilizes various forms of storytelling, ranging from oral to puppetry, and takes us on Tatoyan’s self-discovery. I have never seen anything quite like it before. It is a question most immigrant children like myself know well: where is home? Is home where I was born? Is home where I come from? These questions are answered in Azad, and sometimes, are left unanswered, showcasing to the audience that it is okay to have a difficult time discerning our identity.

I left the playhouse that evening…different. I’ve never been to a space that allowed me to know that my struggles with identity aren’t something I deal with alone. In that room, with an audience of old and young, Armenian and non-Armenian, we were all bound by a common thread: the desire to be free.

Be the first to comment