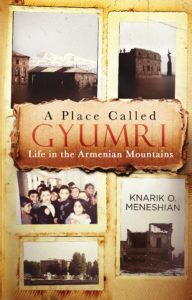

A Place Called Gyumri: Life in the Armenian Mountains

By Knarik O. Meneshian

Hairenik Press, 2020

276 pp.

$35

Knarik Meneshian’s A Place Called Gyumri: Life in the Armenian Mountains is an absolutely fabulous account of the year (2002) she and her husband Murad spent in the earthquake-ravaged city of Gyumri teaching and trying to help its people recover from their catastrophic losses. I say “fabulous” both in the usual sense of “fantastically good,” “wonderful,” and in the original sense of the word—“a dimension other than the one we are customarily conscious of, which is engaged with, but simultaneously outside of, mundane reality.”

Knarik is the narrator. She always speaks directly, but never matter-of-factly. Indeed, her meticulous presentation in exquisite detail—of locations, conditions, items, sights, sounds, smells, tastes, events, and, above all, personalities—is always a vibrant surface for her deep connections with what she experiences as upwellings of the poetry that is human life—haunting, painful, tragic and also divine, luxuriantly sensual, joyful, even triumphant. To make that poetry explicit, Knarik quotes a number of famous Armenian poets, and from time-to-time several of her own powerfully evocative poems.

Her soulful identification with the people—the beggars, the professionals, the scoundrels, the morally and ethically majestic— all trying their best to cope with the devastation of the earthquake’s aftermath, as well as decades, if not millennia, of social, economic and political upheaval and dislocation, makes these people come alive, irresistibly palpable, adventurously concrete and real. Knarik and Murad interact with all of these people with kindness, and also, when called for, with strong ethical purpose.

Of the many examples, here are a few that struck me with particular force. There’s Ashot, the Meneshian’s jovial but crooked landlord, the tomato vendor who allows her customers to choose their own tomatoes—the freshest, of course—but, in the somewhat mysterious bagging process substitutes rotten tomatoes, a circumstance her clients don’t discover until they’ve gotten home and are ready to make dinner.

At the other end of the ethical spectrum is Dr. Amatuni, who is on staff at the city’s hospital, working tirelessly day and night to upgrade her patients’ care and improve their health outcomes. Dr. Amatuni even makes house calls on her outpatients. When Murad and Knarik contract pneumonia, Dr. Amatuni makes sure they get the appropriate antibiotics and checks up on them daily. Indeed, the good doctor had graduated with honors from Yerevan State Medical Institute and practices the most advanced medicine circumstances permit.

Bizarrely, however, we learn that the treatment for a bout of pneumonia which Knarik suffered later on, which was prescribed by another doctor who’d likewise graduated from a medical school, was considerably less informed by modern medicine. Indeed, that prescribed treatment (which the Meneshians did not follow) stipulated that Murad should draw a circle with iodine on Knarik’s back in the area of the infected lung, then (once more with iodine) mark the center of it with an X. The doctor assured her patient that, “This will cure the pneumonia” (pp. 152-153).

Then there are the children of School 21, who are innocent, honest, for the most part good-natured (despite the squalor and ruin in which many of them live), energetic, hopeful and hungry to learn. They respond with great enthusiasm to Knarik’s creative teaching methods and lead the educated, and educating, elite of Gyumri in adopting the Meneshians as true Gyumrians. The children are clearly the future of the city!

At the same time, Knarik is not afraid to confront us with sad, even tragic, stories, like that of the man lying lifeless in the street, probably a victim of starvation, disease, exposure or the evident indifference of his fellow Gyumrians—maybe all of the above.

Perhaps the most poignant of the “fabulous” tragedies Knarik offers us is the story of Lala, 38 years-old, who is severely handicapped both mentally and physically. Knarik’s poem about her is powerful and heart-wrenching. Here is a short excerpt (pp.111-ff):

“Lala is little,

Not because she is a child,

She never finished growing.

Forever her mother’s ‘baby,’

Her father’s ‘if only.’…

She utters sounds

Only the Lord and her mother understand…

‘Ahhh, ahhh!’ she sings as she sits on the floor and claps…

Lala’s mother looks at her ‘baby’ of thirty-eight

And sighs.”

In all of this, and much more, for Knarik the life of Gyumri in that epoch is vital, riveting and always illustrative of a reality deeper than its outward manifestations in human circumstances and behaviors.

When I began to read A Place Called Gyumri, I thought I might be smothered by the detail. But a few pages in, I felt the pace of my reading accelerating, until I discovered that the details themselves, along with the depth and compelling power of Knarik’s insight into the realms of psyche beneath them, fueling and lifting them up as dynamic, authentic to human life, urgent and soothing, were pulling me forward to the next page, then the next, and the next. I was wholly captivated as I rode the swells of feelings and pondered the sensitive reflections of Knarik’s excursion into the heights and depths of the spirit—always present, always available, if we have eyes to see and ears to hear.

It’s true this is a book for Armenians.

It’s also a book for everyone.

I started reading this book and I didnt put it down until I finished it. I laughed, I cried, I was intrigued throughout the book. A must read!!