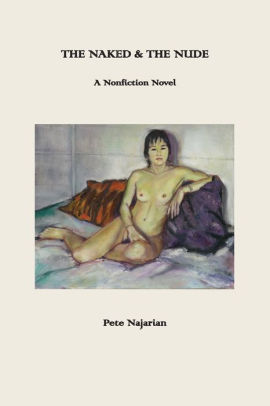

The Naked & The Nude: A Nonfiction Novel

Pete Najarian

Berkeley, CA: Regent Press, 2017

The Naked and the Nude: A Nonfiction Novel (2017) by Pete Najarian is the third in an autobiographical trilogy which includes The Artist and His Mother and The Paintings of Art Pinajian. The book contains many fine color illustrations by Najarian which greatly add to the aesthetic appeal of his “nonfiction novel.” This term obviously implies that Najarian is composing an autobiography based on actual events, yet the genre is not a straightforward “memoir,” for the narrative clearly has the shape of an archetypal mythic journey: the hero’s quest to find his true self. Indeed, The Naked and the Nude is essentially mythopoetic in its structure for throughout we find allusions which recall Homer’s Odyssey or the Quest for the Holy Grail. The Naked and the Nude is also partially epistolary, for Najarian includes in italicized sections letters he had received from the various women in his life.

As with D.H. Lawrence, the figure of the mother looms large in Najarian’s imagination. Zaroohe becomes the mighty symbol of lost Armenia, and there are several affecting scenes in which her son “Pete”—Najarian has recently ceased using the name “Peter” in his published works—and she commune together. He returns often to visit her following his many journeys around the world, rather like Jack Kerouac who constantly returned to his French Canadian mother. Najarian’s father also hovers over the book: crippled by a stroke, he dies when Pete is just a young boy. His difficult life casts a deep shadow over Pete’s life and Najarian laments: “What was loneliness? Why did it cripple me like my father whose last look in the charity ward would be like the end of my life?”

The idea of psychological “crippling” recurs throughout the novel. As Thomas Wolfe asserted in The Story of a Novel: “the deepest search in life, it seemed to me, the thing that in one way or another was central to all living was man’s search for a father, not merely the father of his flesh, not merely the lost father of his youth, but the image of a strength and wisdom external to his need and superior to his hunger, to which the belief and power of his own life could be united.” Najarian describes Pete’s many sexual experiences which are driven not only by intense physical and erotic desire, but also by a powerful spiritual urge which impels him towards transcendence. Najarian describes several intense love affairs as well as countless experiences with ladies of the night whom he seeks out in a seemingly compulsive quest for both escape from his psychological suffering and entrance into a blessed realm of love and acceptance. Here the title which invokes both “naked” and “nude” comes into focus for many of the women with whom Najarian has relationships are depicted in his sensitive paintings which are interspersed throughout. His body and the woman’s body are “naked” and these corporeal experiences are then transformed through imagination into paintings: the work of art is called a “nude.” Art and life are in constant interplay as experiences are constantly described and then recorded through the words of the “nonfiction novel” and in the images which the artist creates: women, sexuality, love, imagination, memory, painting, art and the act of writing are interconnected themes throughout.

The book provides an absorbing history of the counterculture during the sixties during which young people were embarked on precisely the spiritual quest which Najarian describes. He meets Ken Kesey, “a powerful yet soft-spoken and generous man about five years older than I.” Like the Beats, Najarian is an “outsider” to mainstream American culture as an Armenian. Yet he is quintessentially American in the tradition of Whitman, Thoreau and Emerson in his rejection of the materialist values to which our country is addicted and is also—as were they—therefore an outsider to the White Anglo Saxon Establishment. Like the Beats of the fifties and the hippies of the sixties, he is in total nonconformity from the society around him where racism, the Vietnam War and consumerism are running rampant. He suffers several “nervous breakdowns,” undergoes Reichian therapy and tells us after one of his interior crises that “once again I sank into my sickness and became my own nightmare chasing myself through the streets.” He hitchhikes, he is “on the road” like Jack Kerouac, and like Simon and Garfunkel, he is “looking for America.” As he muses upon his identity, he reveals: “And so too was I an Armenian because of my parents, though their tribe had dispersed and I had become an American that was no tribe but a loneliness in search of the kindred I needed for my own survival.”

Najarian recounts his years at Rutgers University, the arrival of Norman Mailer on the literary scene, the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, the cultural life of the fifties and sixties—Willem de Kooning, Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story—and remarks: “We had come of age in the aftermath of the bomb and the concentration camps, and there was no meaning in anything but how to live without hurting anyone, nor any need for any furniture except a table and a chair.” This is also the world which the Beatniks and the hippies of the sixties inherited, questioning whether indeed reality had now become “neither a tragedy or a comedy but a kind of modern mystery play in a world without God or meaning?”

As the book progresses, Najarian includes his friendships with a number of fellow writers at a variety of universities who invite him to teach after he begins to build a literary reputation following the publication of his first novel Voyages (1971). Part of Najarian longs for a settled home life with a wife and children, and he sometimes describes moments of envy when he observes his literary friends who have such a life. This dream of domestic harmony eludes him, even as he acknowledges that such seemingly happy couplings of his friends are often not what they seem.

The book is both a literal travelogue, detailing Najarian’s many voyages across the world as well as a book which depicts the symbolic journey, the archetypal hero’s quest for the Golden Fleece, the home of Ithaca, the Holy Grail. He travels to Mexico, taking with him to read Don Quixote and The Brothers Karamazov; to London in 1962; to India where he visits Bodh Gaya, the place where Buddha achieved enlightenment beneath the Bo tree; to the Armenian monastery on the island of San Lazzaro; to Greece; to Armenia during the 1988 earthquake and to Turkey.

While in Arapkir, he notes “in the slant of the morning light from the window the rainbow colors of the rugs and the pillows made me feel I was entering a kind of vision like Percival finding the Grail, at least for a short while before I too would soon lose it.” And a few pages later he describes the pain of hot water falling on his wounded foot—we are meant to note that he is literally crippled at this point as was his father, and not just psychologically—“as if it were a wound from the bleeding lance in the story of Percival when he lost the grail and would never find it again.” And yet again in a later scene, he describes how he sat above the bank of a river “like the Fisher King looking across the wasteland that had once been his kingdom.” He reads Erich Neumann’s The Origins and History of Consciousness, and it is clear that the quest for the Magna Mater—the Great Mother—is the archetypal quest of the hero for the mystery of life as incarnated in the female as giver of life. But the Great Mother, as C.G. Jung would argue, also has a “shadow”—she is like the Hindu goddess Kali capable of destruction as well as creation. Thus Najarian laments: “I was lost, I was lost, and the gulls gathered round me in a grim and holy silence as if they were angels and vultures at the same time. Would I ever be well? Would I always be separate with the sea so alive and deadly like a great female who wanted to hug me and kill me at the same time?”

Pete’s mother Zaroohe dies at age 101 after spending six years in a nursing home. The scenes with Zaroohe throughout are deeply affecting, especially those depicting Pete’s final years with her. The book closes with Najarian recalling an episode when he was age eighteen hearing Eugene Ormandy rehearsing Brahms First Symphony with the Philadelphia Orchestra.

‘You’re not a cripple,’ he said, ‘you never were a cripple, let go your fear and dance the dance of the ages, let go, let go!’”

The voice here is of course the voice of Pete’s father, who is blessing him to break free of his psychological trauma. Here we have final fusion of the sexual, spiritual, psychological themes of the book which recalls the very last lines of Najarian’s 1971 novel Voyages in which the son and father also speak:

“I’m not going to be crippled, Papa!

My son, he said, I never wanted you to be. Why did you think I did?”

A key turning point in the book is Najarian’s discovery of painting, and he thus joins the ranks of so many writers who have also been artists: William Blake, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs and many others. Najarian’s art work is quite fine, employing a deft use of line, shadow and coloring, catching women in a variety of both erotic and casual poses and revealing a real gift at catching the individuality and personalities of each subject. He includes several landscapes as well as a section devoted to portraits of several of the students he has taught in the Oakland Unified School District as a substitute teacher. And finally, there is a concluding section featuring animals and figures in ceramic. The fact that Najarian has chosen to end the book with these creatures seems a wink on the part of the writer/artist, an affirmation that he has taken his father’s blessing to heart and declares, like William Blake, that energy is eternal delight: the artistic imagination finally leads to the most affirmative creative solution to our exile here on planet Earth.

what a wonderful critique of Pete’s book. Compliments to David Calonne he was “right on.” I read it twice and it was even better the second time and someday Ill return to it again – couldnt put it down. How courageous of the author to reveal so much about himself.