I Was a Star Student in Armenia—Then I Left

There was pain in the upper eyelid and redness inside the eye. At four in the morning, I was alone in a washroom, looking deep into my eyes through a large and limpid mirror. There was no point in sleeping, as I was going to be woken up in two hours anyway by a dramatic alarm clock, blaring the incessant rhythm of failure.

I had successfully failed all my tests at my new international school in China—all the science experiments and subsequent lab reports. In Armenia, I had been proud and successful in school. I often reminisced about my education back home, while performing lab experiments with great difficulty at my new school. I would recall my perfect scores, my ‘ten-out-of-tens,’ my red diploma of excellence, my teachers praising my intelligence and the wall at school that featured my picture among the best in class. Meanwhile in China, I was suffering with a pH meter to measure the acidity of the water sample, like the inability of someone who previously lived near the equator had to adjust to a winter in Siberia. In fact, my reason for suffering was fundamentally the same; I had never experienced an environment like this before, that is, an environment of true academic rigor.

We didn’t learn how to take theoretical knowledge to practical expertise. We didn’t transform words into action. We didn’t derive our own conclusions which would potentially counteract the textbook’s arguments. Consequently, we didn’t learn.

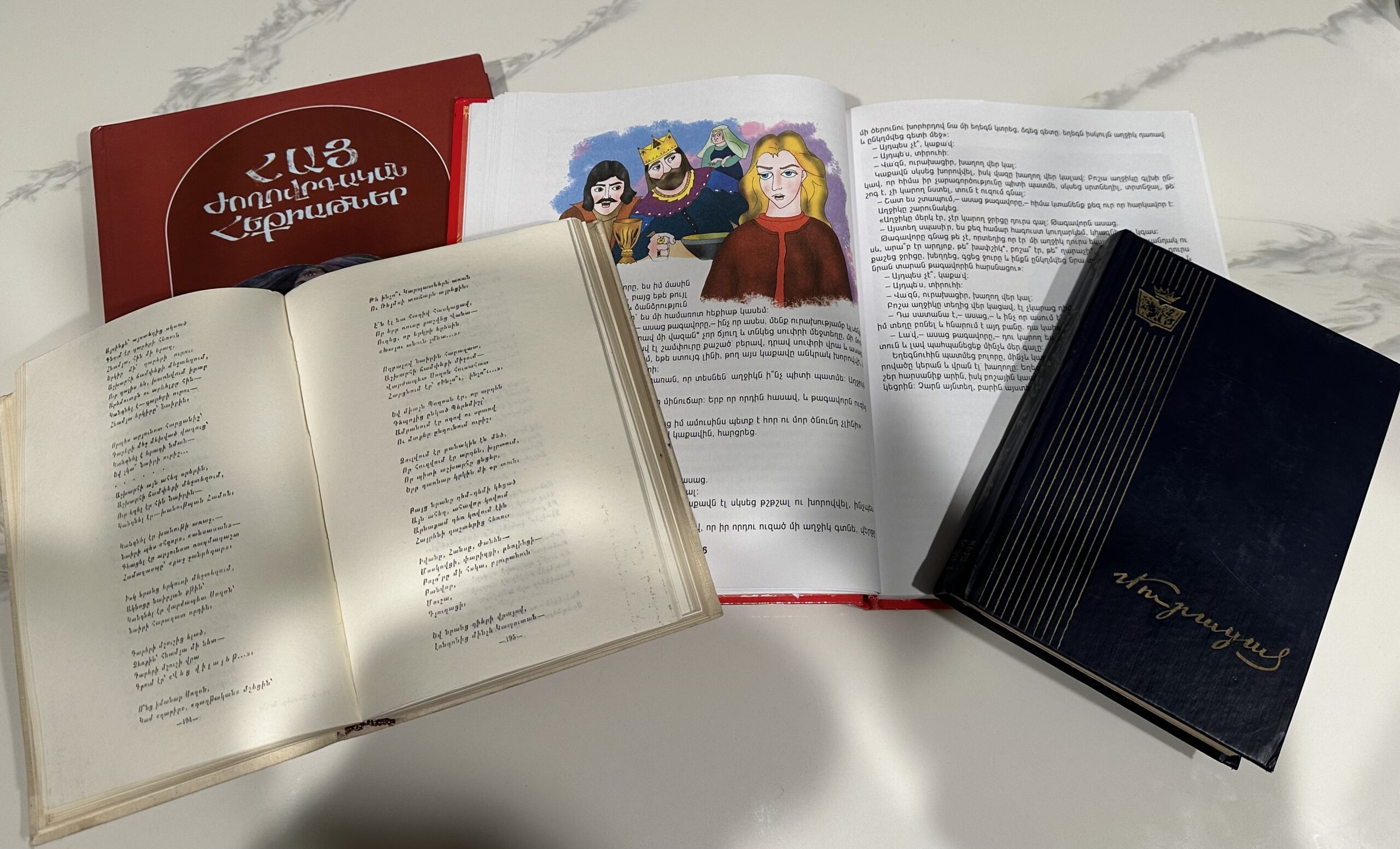

I thought about my chemistry teacher in Armenia reading the lab experiment out loud from the textbook, in the same way someone would recite a poem for a large audience. I also remember these readings floating in the air, untouched, untested, and un-lived, as if the danger of failing to follow the instructions were too great; as if there were a threat of harming the tools (and I was unsure if any even existed); as if there were a danger of learning. ‘Lab experiments’ were traditionally followed by ‘lab reports,’ in which an award was always offered to the one who best summarized and paraphrased the instructions from these textbooks.

And then, there I was in China, in a school where I was supposed to measure the pH and turbidity levels of water, determine the texture of soil, and then submit a lab report with graphs and diagrams created in Excel. My Armenian school, conversely, had only one computer for all 13 students, each of whom were expected to learn how to use Excel in half an hour during our informatics class. Evidently, none of us ever did.

We didn’t learn how to take theoretical knowledge to practical expertise. We didn’t transform words into action. We didn’t derive our own conclusions which would potentially counteract the textbook’s arguments. Consequently, we didn’t learn.

Instead, we treated the textbook as an authority, as a dictator with absolute power and undeniable truth. We killed potential scientists inside the walls of that classroom and within the limits of that chemistry textbook.

One might argue that our failures in education are a result of material scarcity in Armenia: the absence of necessary tools, of the unavailability of basic equipment, of the insufficiency of financial funds. But I would encourage critics to look behind and beyond those arguments. I would recommend looking deeper into the mirror of our society, and deeper into our own eyes.

Once, during an Armenian literature exam, I was asked to answer a multiple-choice question about Hamo Sahyan’s birthdate. For a minute, I thought I was in the wrong exam hall, somewhere a history student should be. For a minute, I felt extremely sorry for the creator of that question, the person who had made Sahyan a box to tick, as if there were nothing to analyze, nothing to explore, nothing to understand, as if everything he was and everything he did could be encompassed in a four-digit number.

For a minute, I felt extremely sorry for the creator of that question, the person who had made Sahyan a box to tick, as if there were nothing to analyze, nothing to explore, nothing to understand, as if everything he was and everything he did could be encompassed in a four-digit number.

Ironically, during a literature studies exam at my international high school in China, I was permitted to write about the writer’s birthdate if, and only if, I was going to discuss how that date had contributed to the writer’s personal context, to his or her writing style, to the themes and messages revealed through his or her literary works. To be honest, I am highly skeptical of the need for tools and finances in the development of appropriate, necessary and relevant exam questions; and I determinedly require the presence of those questions if examiners are anticipating intelligent, insightful and reasonable answers. A writer’s date of birth will soon be forgotten, but the ability to observe and analyze, to think and discuss, to understand and assimilate his or her writing will remain, endure and persist.

It was because of or, rather, thanks to those 4 a.m.’s; thanks to those ‘self-gatherings’ during which I peered deep into my own eyes; thanks to those late night self-studies in China that I managed to transcend my failure, reach some benchmarks, and achieve both minor and major ‘triumphs’ against the well-outlined boundaries of my Armenian textbooks. It was thanks to every tiny teardrop, to every second of pain in the upper eyelid that I got admitted to my dream university and managed to draw a small sign of a smile below my parents’ eyes, now shining with happiness, but up until then had reflected nothing but anxiety and disillusion since I had come to China, the place I learned I was not as excellent as they ever thought I was.

I do not want any other Armenian student to cry while writing lab reports, plotting graphs in Excel or analyzing literary texts in a foreign community. I do not want an educational system in which only those from private schools win the international Olympiads or get admitted to the best universities in the world. I want fairness in education, equality in opportunities and equity in the defining of boundaries. I knew the capabilities of my fellow students in my Armenian class and their potential if we were ever taught a decent lesson. Now, as someone who has experienced both the pain and the delight of expanding boundaries and exploring the potential of my own mind, I am asking for a redefinition and reconstruction of education for a fair and equal, interdisciplinary and creative Armenia.

I want an Armenia of scientists and writers, of discoveries and innovations—an Armenia where looking deep inside the eye is no longer a source of fear or shame, but a path to clarity in vision, to strength in action and to consistency in progress. I am asking that we look deep into the eyes of our nation, even if it pains us to see what’s there.

Great piece. Having attended Armenian public schools until 9th grade (in late 1990s), I had the same experience: old Soviet-style memorization, emphasis on facts as opposed to analysis, lack of critical thinking, no hands on experiments, etc.

However…your article seems to imply that UWC – a world class educational institution – is the same as public education in China. As though Armenia is light years behind China. My guess is that Chinese schools have similar shortcomings as public schools in Armenia. But both systems have a lot to learn from UWC, which incidentally has a branch in Dilijan, Armenia.

I would also encourage you to read up on Araratian Baccalaureate (araratbaccalaureate.am), which has been fully formulated and tackles the problems of modern education in Armenia; and follow the work of Ayb Educational Foundation (https://foundation.ayb.am). Perhaps your next article can be about the good work they are doing and the wonderful possibilities ahead.

Dear Hovsep, thank you for your comment. Although I am currently studying in China, my school is not related to Chinese public education, so I did not try to draw parallels between the Armenian and Chinese systems. My article is about quality education, something that, as you mentioned, UWC, Araratian Baccalaureate, Ayb or Shirakatsy Lyceum provide. Fortunately, the number of these schools and programmes is increasing and the quality is improving, but I cannot say the same about the public education, improvement in which is crucial if we speak about equality in opportunities, because (at least for now) not everyone can attend the private, quality institutions that you and I mentioned about.

I truly hope to have the opportunity to write a much more positive article in the near future, an article about the existence of wonderful possibilities for EVERYONE.

Very emotionally driven article, nice read. You are absolutely right. Schools in Armenia failed us, all of us. Those same schools are continuing failing the new generation of genius Armenian minds.

Didn’t fail me. Please speak just for yourself.

Curious… would you say it is more a lack of funding for appropriate computers and supplies – or is the political situation the reason for the current state of memorization-passing-as-education.

I would say both, as well as the long-lasting impact of the Soviet Union on our history, politics, economy, society and, consequently, education.

Yes, there is a difference in quality of education between where you were and where you are. But you can’t blame Armenians for that- lack of funding for public schools and education at large, differences in access to education and educational opportunity between social classes, and failing educational systems are not an exclusively Armenian issue. These are political, economic, and human issues.

Even in wealthy Nations like the USA, schools fail children. Armenian schools produce lower science scores than Chinese , but higher than the USA. So blaming Armenian mismanagement for a global issue is a little unfair.

I do not ‘blame’ Armenians, I do not say the educational systems in other countries are perfect. I say that we are doing much less than what we could do and what we should do. We are not reaching our full potential at both the individual and the institutional levels.

Saying that wealthy nations also have this problem is not a solution to the issue; it is a self-consoling behavior which often leads to deterioration. And, to be honest, I prefer constructive criticism (/’blaming’?) to closing our eyes to the obvious.

Milena, this is a well-written article! I was a student in Armenia up until 8th grade, and while I see where some of your arguments are coming from– I do happen to disagree with you. After moving to the U.S., and attending a top-ranked high school in California– I was truly surprised.

Surprised not by the amazing application of engaging assignments and real-world cases, but rather by the narrowness of the American education system. As a fellow Armenian who studied back in our homeland, I am sure you recall taking classes that focused on medieval history, geography, and other liberal arts subjects. Yet, such courses simply do not exist in many foreign educational systems (on the K-12 level at least). So, as someone who has studied in both Armenia and the U.S. (and will soon be graduating from one of the top U.S. universities), I can assure you that the Armenian education did not fail us– it gave us a wide array of knowledge, which in turn has made us extremely well-rounded… in every sense.

And while your article provides some concrete examples, I think it would be far more helpful to make it a bit more specific and frame your issues.

As to your point about Excel– I do not think Armenian schools have enough funding to allow students to learn these valuable computer skills. If you are motivated, you’re welcome to do that on your own. My top-ranked high school (which had an emphasis on engineering, math, and technology), did not teach me Excel either! However, I needed the skills, so I learned them by myself.

All in all, the points you are making are valid, but I think the educational system is not to blame. Armenian schools give its students a great base, which is often better than within other foreign edu systems. However, as always, funding is a huge issue. There is no lack of talent in Armenia, but to use it to its full potential, schools need to be equipped with costly resources (for which, unfortunately, there is often not enough money).

Thank you, Henri. I completely agree with you. When I came to the United States of America in 1990 at age 16, I started attending high school. Even though my English wasn’t great, the knowledge that I brought from Armenia didn’t only help me to learn English much faster, but also to excel in other subjects. Why do you think immigrants, who came from Armenia were able to so quickly adjust to their new country? The education, which we acquired there in schools and universities was the key for today’s fast growing and successful diaspora. Do you know that UK recently decided to change their education system with the Soviet’s education system?

Dear Henri, of course I recall “taking classes that focused on medieval history, geography, and other liberal arts subjects;” I had to memorize all the facts, dates and names. But we did not analyze the reasons and causes behind the events, thus we didn’t learn the essential and we lost the opportunity to understand and learn how to avoid the historical mistakes of the past in our present and future.

Please note that my article is not about the American system, but about a type of educational system that already exists and from which we have so much to learn.

And yes, you and I and many other Armenians abroad managed to learn Excel on our own, we managed to gain a lot of other important knowledge and skills on our own, but it is not because of the “great base” that the Armenian educational system gave us, but because of the talent, creativity and hard work that Armenians have had the necessity to acquire and possess in order to survive and overcome the difficulties and the harshness of our history.

Dear Tereza, I think I answered your questions in my response to Henri’s comment. Furthermore, the Soviet’s educational system is completely different from the Armenian system that we have today. The Soviet’s system had great strengths but also weaknesses, while the Armenian system today, unfortunately, depicts only the dark side of the Soviet’s education.

Dear Milena,

Thank you for taking the time to reply. I will reiterate my point: while Armenia has systemic problems in its educations, there is a concerted effort to do something about it. Your article would be more complete and better rounded if you included this fact. For example, starting September 2018, Araratian Bacchalaureate had a pilot program and 100 teachers from the public school system from all over the country have undergone a 1-year, rigorous, full-time preparation. The pilot program will eventually expand to the entire country, and not just Yerevan. (Currently there is a hiccup with the new Minister of Education…)

Araratian Bacchalaureate is not intended for the select few in private schools.

https://www.evnreport.com/raw-unfiltered/araratian-baccalaureate-transforming-the-future-or-creating-selective-education

“In 2015, however, following negotiations with the Government, the strategy was altered and it was agreed that AB will be introduced in all high schools as a fourth track along with the Arts and Humanities, Sciences, and General tracks to ensure that each student has the chance to be included in the program”

Dear Hovsep,

Please take a look at this article http://panarmenian.net/m/arm/news/263921

I cannot say who is right and who is wrong, but the fact that the future of this program is undetermined and obscure restrains me from writing an article with a positive note. That being said, I really hope that something positive and constructive will happen in the near future and we will have an exemplary system worth writing about.

Thank you Milena for your critical and thoughtful piece which encourages much needed further dialogue. Armenia’s education system has many shortcomings, not the least of which are inadequate overall funding for education, outdated pedagogy, insufficient teacher education, and inadequate management. The country’s latest move to combine the Ministry of Education with other ministries is somewhat disconcerting, raising the question, “is education a priority?” Armenia’s potential is waiting to be tapped. While there are some successful shining stars (pilot programs, charter-like schools, after school programs and institutions, etc.), these are insufficient to sustain the country’s development. A national education strategy is needed.

Dear Sharistan, I couldn’t agree more. Thank you for your insightful comment.

Dear Milena, you are an exemplary Armenian for the good work of writing your articles which will have positive effects on Armenian educational system for sure. Thank you

Dear A.Napetian, thanks a lot for your kind words.