Special to the Armenian Weekly

I do not know how my fate would have unfolded in Azerbaijan, if all that happened to our family—and the Armenian people who once inhabited it—had not happened.

But I can say with certainty that I do not want to know. I do not see myself there anymore. We were exiled from our country, from our city, from our home. It no longer exists for us. We have not been there since Aug. 1989. And never again will be. I hope.

Today, decades later, it seems odd to me that I was even born in Baku at all. Why Baku? Why not in Artsakh; my ancestral motherland, in the village of Khndzristan, the birthplace of my father Aleksandr Djavadi Mirzoyan, and a large part of my deep historic Melik-Mirzakhan lineage?

My mother, doctor Victoria Solomonovna (Soghomonovna) Mirzoyan, was once chief of medicine at Melikov Hospital #6 and head physician of Pediatrics, in the Kirovsky district of Baku. Soon after our forced exile from the city, she fell ill with cancer and passed away in Moscow, never having lived to see our emigration to the United States.

Why did she get sick? I don’t believe in those terrible days that it was possible to process the horror of what was occurring absolutely independently of one’s own body. The cool and collected mind of a doctor was joined by a warm and loving heart of a woman—wife, mother, grandmother, upon her the responsibility of family.

The Sumgait pogrom horrors of Feb. 1988 came as a complete shock and left an indelible scar and a terrible pain in our souls. How naive I was, to have offered our home as sanctuary to my friend, a teacher, Lyudmila Israelyan and her family after they escaped the Sumgait pogrom. But they never made it to us in Baku. They were right to consider Baku no less dangerous for Armenians. They fled to Russia, with relatives awaiting them. Yet my mother still had faith in law and order.

“Graves of 26 Baku Commissars lie here, no such thing can happen here!” She spoke with conviction.

Mom, my dear brilliant mother, how could you have believed it so? Meanwhile, rabid crowds of rioters cried out in Azerbaijani: “Karabagh is ours! Death to Armenians!”

It was happening in the center of the city. It was happening all around.

In those terrifying days, I lived with my five year old, Julie, at my parent’s home. It seemed safer there. Or at least higher off the ground—the fourth floor.

Behind the windows of my parent’s apartment, in the third micro district (micro-rayon), stretched Tbilisi Avenue, along which, in those nightmarish days, rampant, extremist-minded Azerbaijanis marched, seeking to attack and kill Armenians in sight.

Like a scene from a horror film, I recall that night and the voice of our neighbor calling out as she passed our home: “Clockmaster! Clockmaster! Sasha! The workshop is on fire!”

We ran to the window. The fire department already arrived, all was covered in foam. Everything that could burn down, did. Nothing remained, nothing to salvage—the business was gone.

Dad taught mechanics at the Repair of Precise Mechanisms factory. He had taught many the craft. Word about his mastery spread wide and his kindness was known among strangers. Just as patients would often be referred to mom for treatment, clients were often referred to dad for watch, clock and jewelry repair. For the retired, fellow countrymen from Karabagh, students and enlisted soldiers, he repaired at no charge. “Where would they get the money?” he would say.

Dad stood on the ashes of his shop and looked dolefully at his “breadwinner,” as he called it, searching for the cause of the fire. My sister and I stood near, trying to remain optimistic so that dad would feel supported.

“Master, it was a spontaneous ignition,” said one of the firefighters.

“What do you think could have self-ignited, if I have not worked in over a month?” asked my father.

“There’s a canister,” I said, pointing to an empty vessel dumped next to uncle Alyosha Dolukhanov’s burned down cobbler shop.

But the fireman insisted: spontaneous ignition.

Dad knew that no one would do anything. The country was derelict, he felt. The commandant, a Russian officer, arriving with a group of soldiers upon our appeal, spoke intently: “Forgive us, but we cannot handle this. Not far from here, in the Khutor, Armenian homes are ablaze. We are barely able to manage saving and sheltering people. My advice to you: leave the city while we are still able to help you.”

By morning, a young, Armenian police officer was sent to our home.

“I beg you, Alexander, sign that it was spontaneous combustion. I must close this case. Otherwise, they will not let me out of this city. And I have family.”

Of course, dad signed the papers.

Sometime later, a pre-dawn call woke my father. It was my cousin, Karen Ambartsumov, the son of my mother’s sister Amalia. His car was set on fire. Flames blazed below the windows of his apartment in Ahmedly, where he lived with his wife, his mother and three young children, the youngest of whom was three months old. Dad and I went to them. And although a molten plastic bottle of gasoline still lay on the roof of the charred car, Papa and Karen signed another vile “spontaneous ignition.”

And yet, my mother still believed all would work out. It just could not be otherwise! But a tearful call from Arega—mom’s relative and nurse, who lived with her family in a house built by her own husband Ashot Musaelyan in the Kirov township—opened mom’s eyes.

“Victoria Solomonovna, we are in the street! We were kicked out of our home!” cried out Arega.

“What? Who? How dare they? Is there no Soviet power? Run to the police! Run, they will help!” mom repeated anxiously and loudly, trying to shout over the cry of her beloved.

“I’ll call their charge, Comrade G,” mom added, ready to hang up the phone. Arega cried out “Dr. Mirzoyan, Vika jan, the police put us out. We are leaving for Armenia. And you should leave.”

Both cried. They knew that they were parting for good.

We continued to go to work, while ongoing anti-Armenian demonstrations carried in the streets, and Armenians and their homes were repeatedly attacked.

In the teacher’s lounge at school 151 where I taught, Armenians talked of leaving Baku. The majority spoke of moving to Armenia.

This terrible year began and ended with the misfortunes of the Armenians. It was Dec. 7, 1988. We learned about the terrible earthquake in Armenia. We were in shock and the grief of the tragedy was felt. In tears, we watched the footage in the news and glued to every article in the newspapers.

The Armenians suffered, while Azerbaijan rejoiced. Cheers, fireworks and festive gunfire was heard in the streets of Baku. News of the earthquake in Armenia was transmitted on Azerbaijani television and the announcers barely hid their zealous smiles. Celebrations in the streets lasted the entire night. They were not ashamed.

Fervent shouts below our windows, declaring the wrath of Allah, sent a wave of horror and revulsion through us at the realization of what kind of people we lived next to. We feared for our parents. We feared for our children. We feared for ourselves.

“The horror. What horror! Poor Armenia. They have so much of their own tragedy to deal with and now the aid to our refugees fell upon them too,” my mother said.

“Yes. It’s terrible. We will help Armenia by not obliging her with our care,” concluded father.

The planned move to Armenia was abandoned. The country already had plenty to deal with. We sought other ways out. We continued to walk the streets of Baku, take public transportation, interact—all while looking over our shoulders or simply keeping our gaze low.

Relying on the USSR army peacekeeping, we gradually got used to its presence in the city—which provided a sense of security. But not always, of course. Although soldiers and military vehicles were posted at many intersections of the city, the extremists persisted.

My sister Ida, who worked in the Baku State Philharmonic choir, managed to miraculously escape from a group of pogromists that burst into the M. Magomaev great hall in search of Armenians. Colleagues managed to hide her and help her escape. She never returned there again. It was hard to believe that this was really happening, in a once peaceful and, it seemed, kind city.

Returning by foot from ballet class at Gagarin Pioneer Palace with my daughter, we walked to the metro station Baki Soveti (now İçәrişәhәr). Meanwhile, a band of pogromists marched on the Chkalov Street (now Niyazi), from the boulevard up to Kommunisticheskaya Street (now Istiqlaliyyet). Seeing them, I realized we would not make it to the metro station. We ran across the street to the armored personnel carrier (APC) stationed on the intersection. Two armed young Russian soldiers hid us behind the APC.

“Are you Armenian? You should leave the city while we’re still here,” the soldier spoke.

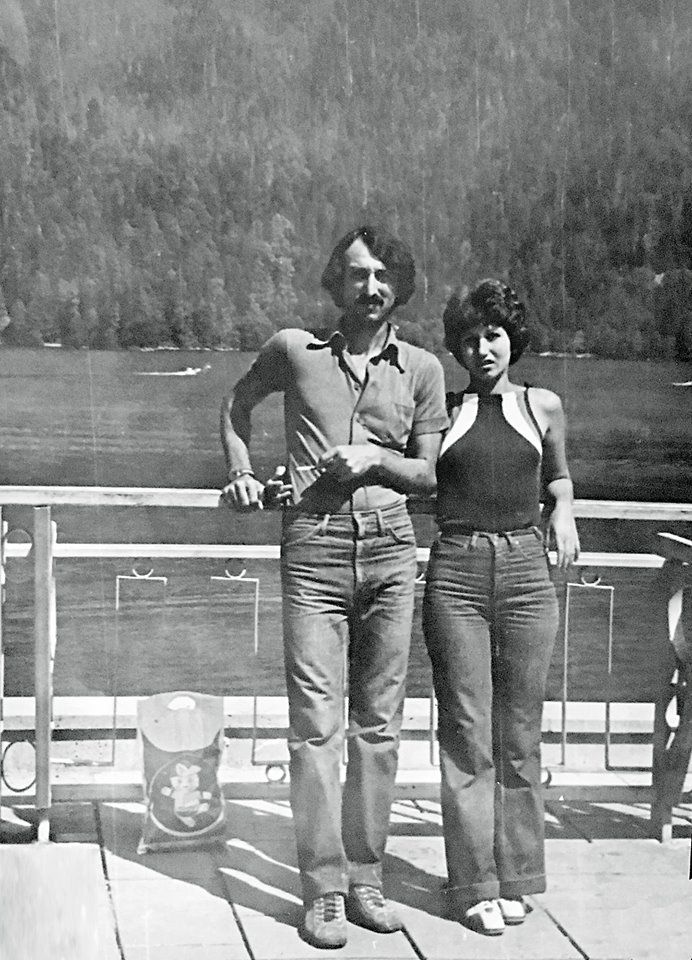

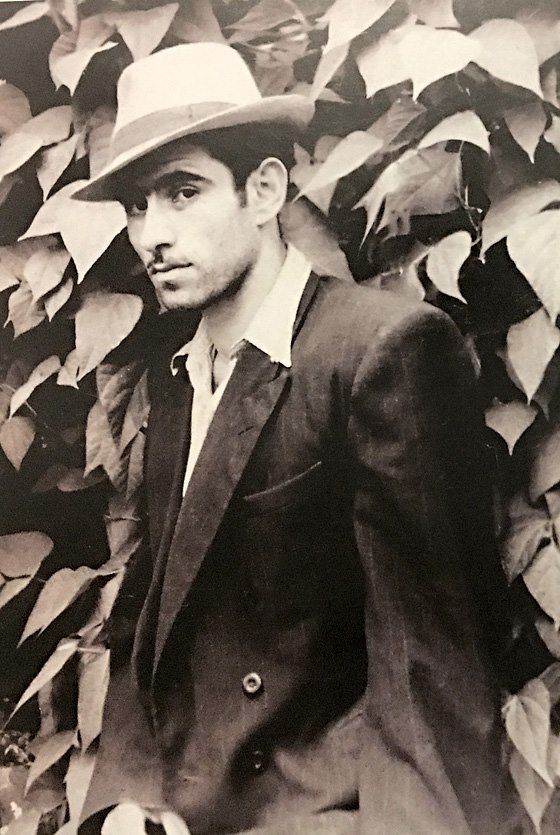

My husband, Albert Asriyan, a well-known musician, violinist, composer and arranger, was on tour of the Soviet Union and Azerbaijan as part of Gaya state orchestra and the rock band Talisman, which he then directed. We awaited his return. His last show was at the end of the summer of 1989. Shortly after, we took off, along with all the members of our large family.

We managed to flee Baku with the help of friends and mom’s patients before the last Armenian Baku pogrom in January of 1990. We found ourselves in Moscow, but the shadows of those horrible events continued to haunt us for long after.

Mom was born in Baku in 1923 and left it forever in 1989. A doctor, who provided 40 years of care and service at one institution, remained forever there—in the USSR. She never could imagine herself outside of her home city, outside of her great country, outside of her vocation. A long line of Armenian refugees of Baku joined our family in Moscow in wishing her a final farewell. They were her former patients who knew their beloved doctor throughout their lives and the lives of their children, and trusted her both in their former homeland and in exile. After burying my mother, we were preparing to emigrate from Russia. Having spent four complicated years in Moscow, we were finally granted permission to leave.

This was 1993. By this time, our family had grown as we welcomed our little one, Kristina.

We flew to New York, having known very little about it. All we knew for sure is that our relatives are waiting for us. A year prior to our arrival to New York, Ruzanna, Albert’s youngest sister, emigrated with her family. Soon joined by the arrival of their other sister Elza with her family and their parents—Sirvart Ashotovna Karnizyan (whose mother, Aikanush Ter-Terian, originally from Trabzon, escaped Armenian Genocide of 1915 at the hands of the Ottoman Empire when she was thirteen) and Mikhail Avanesovich Asriyan (whose mother—Anaid Abramova, born in Shushi, escaped the massacres of Armenians in 1920, having lost much of her family).

Albert and I, along with Julie, now ten years old; Krisina, two years old; and my father, Alexander, settled in New York. Thus began a new chapter in our lives in immigration. The page was turned anew in our destiny—but this was a different world entirely…

***

A version of Alexander’s story of escape first appeared in Moscow’s Zham (Жам) magazine (in Russian).

Wow, it feels like I read about my family. My mom was also a doctor, but general therapy. And she worked at polyclinic #8 also for more than 40 years. She managed to survive and got a chance to leave USSR and come to NYC. She passed away 5 years ago…

Deeply moving. A lesson for today’s Europe. Thanks, and some tears, from an Englishman who is proudly 3/16 Armenian, Minas family of the diaspora.

Please send your story to the BBC program HARDtalks to Stephen Sacker and his gangs … who questioned our Polite, Honest foreign minister, Zohab Mnatzaganian…Who did not answer his aggressive question about Baku’s criminal acts against 400.000 Armenians during the years1988-89…

“And yet, my mother still believed all would work out.” I read that sentence and felt a chill. So like the reason so many of my people did not leave Germany in the late 1930’s. Tragedies both. But now we have our homelands back, Armenians to Armenia and Jews to Israel. I pray we both stay in them always.

Correction: In contrast to the Jews, Armenians now have only the smaller portion of their historical homeland. 2/3s have been stolen by the Turks and now form eastern provinces of Turkey. This is the major difference in the Armenian and Jewish tragedies.

God Bless Albert & Ivette Asriyan & Family from their survival from the Barbaric Azeri Turks from Baku. We thank their story of survival which the world should read. We wish their family the best.

Thank you for your kind wishes, dear friends. ❤️

Please send your story to the BBC program HARDtalks to Stephen Sackur and his gangs … who Questioned our Polite, Honest foreign minister, Zohab Minatzaganian…Who dod not answer his aggressive question …about Baku’s criminal acts against 400.000 Armenians during 1988…