WAHPETON, N.D.—Like their name, Norik and Irina Astvatsaturov praise God for their artistic talent every day.

They also thank the Lord above for keeping their family safe and secure during the turmoil they faced in Azerbaijan. As proud Armenians from Baku, their faith and family show no compromise.

“Because of war, we were forced to evacuate our homes,” Norik recalls with disdain. “It was terrible. Our people had a very hard history, a very bad time.”

The family decided to apply for refugee status in the United States. It was not easy. For two years, they held their breath, counted their blessings, and stayed strong.

Today, Norik and Irina are firmly entrenched in North Dakota. A Methodist church in Wahpeton sponsored them as a refugee family. With just a few dollars to their name, the money was spent at the airport.

“We were hungry and we bought pizza,” Norik recalled. “After living in crowded rooms in Yerevan, we were now in heaven. God has given us the opportunity to live in this country with good children and grandchildren. They represent our entire life.”

Norik’s workbench is a constant cadence of tapping sounds as he turns metal into exquisite forms of art. His wife enjoys a similar handicraft with beadwork.

Their folk art represents their heritage, history, and life’s experiences and is currently on display at the Heritage Center and State Museum through the end of this genocide centennial year. It carries an estimated value of $100,000.

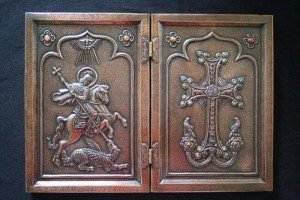

Titled, “God Given: Cultural Treasures of Armenia,” it has served as a two-fold eye-catcher with locals. Norik’s work consists of copper and bronze repousse with inlaid semi-precious stones, many with Biblical themes and ornamental pieces. Irina dedicates herself to Russian and Eastern European techniques to create colorful beadwork on black velvet.

It’s done the old-fashioned way by hammer and nail with precise hand-eye coordination.

“Metalwork dates back 2,000 years or more,” he explains. “I wanted to try it as a 19-year-old and have continued through the decades. I always try to surprise myself. It means that I have not died, that I live like art. That is the beauty of creation.”

First came an Armenian cross for his church as a gift to the people. It was made from aluminum and was very hard to maneuver. From there, the passion turned to jewelry boxes, historical figures, icons, and decorative plates.

As many as a thousand hits on each side go into the process, depending on the size and difficulty of the subject. There’s no room for error, Norik says. It’s that precise.

“With Norik and Irina, their work really does reflect their culture and history,” says Troyd Geist, a North Dakota folklorist. “It’s an interesting, rich history that involves a part of the world not many of us know much about. It touches upon very real situations going on in the world now—the tensions between Muslims and Christians… We can learn from them.”

Irina was a teacher in Baku and learned beadwork as a child. Her images include elaborate icons, birds, and flowers.

They met at an art studio in Baku 38 years ago and have 2 children, Anna (Turcotte) and Mikhail, along with 4 grandchildren.

“My parents complement each other in a sense that she guides his compositions with her advice and he does the same for her,” says Turcotte, a Maine attorney and author of Nowhere, a story of exile. “One thing my dad could do here and not Baku is using his metal embossing skills to create traditional Armenian Christian art as opposed to non-religious pieces.”

Their exhibit is enhanced with an award-winning publication written by Geist, featuring Norik’s work. He is a recipient of the prestigious Bush Foundation Fellowship.

A short documentary was shown repeatedly in the museum’s new theater. The film explores Norik’s artwork in relation to the turmoil in Baku and the Nagorno-Karabagh region between Christian Armenians and Muslim Azerbaijanis.

“My parents built our lives by putting aside their own ambitions and dreams,” Turcotte added. “My father worked 12-hour shifts in a wood-processing factory for 23 years before retiring. My mother worked odd jobs to support the family financially. They came home to their art evenings.”

In North Dakota, the family found peace and security for the first since the Karabagh liberation movement began. There are no Armenian churches or communities in the state. The closest is inside the Minneapolis area, which is four hours away.

There are Armenian families, though they’re separated by hundreds of miles. But that didn’t stop them from raising their children within the Armenian culture, not to mention the language.

“No one knew what an Armenian was,” said Turcotte. “My parents used their art and cooking skills to educate fellow North Dakotans about their rich history and culture by hosting dinner parties. That way, they could also practice their English.”

For the first six months, the family lived off food stamps. No employer would hire them because of the language barrier. Finally, Norik began working at the wood processing planting in town while Irina helped out in the high school cafeteria.

Due to Norik’s limited exposure to the Armenian folk art world, he’s relatively content about being a Baku Armenian who continues to make an imprint in the American mainstream.

“My parents maintain their Armenian identity through art, the story of Armenians they tell anyone they meet in the Mid-West,” Turcotte points out. “It’s the history they have taught their children and now their grandchildren.”

Beautiful story thank-you for sharing may God keep blessing your family

I have known this family of Irina and Norik since they move to Wahpeton,ND and become part of our church family. They are all wonderful people who have always represented their Armenian culture with honor and pride. I am happy that they have have contributed so much of their art and creativity to our community and to the state of North Dakota.

Marlin Galde

I live in ND and there are more Armenians than Azeris. I’m Armenian and a large population of Jamestown, ND is Armenian. They came here durring the Genocide. This is one of the reasons North Dakota recognized the Armenian Genocide. Didn’t know the state was boasting a large Azeri oil workforce either, mostly Americans from Texas, Wyoming and other oil and gas producing states. Other than that, great Article.

{“North Dakota, where the state boasts a large population of Azeri oil workers.”}

I don’t get this: why would ‘Azeri’ oil workers be in North Dakota ?

If they are oil _workers_, they’d be in Baku.

Azerbaijani businessmen connected to the oil business residing in ND, I understand.

But why would ordinary oil workers move from Baku to ND ?

Surely ND is not lacking local people to work in whatever oil business there is in ND.

What am I missing ?

Avery, most of the businessmen that are not American are either Russian, Canadian, French (Slumbergher, biggest oil company in area) or Armenians in the Bakken. Article needs to fact check.

Hey thanks for redacting the Azeri oil workers mumbo jumbo.