Special Issue: Genocide Education for the 21st Century

The Armenian Weekly, April 2023

My first steps in teaching in the US were at Clark University as a doctoral student and teaching assistant for two exceptional professors—Taner Akçam and the late Robert Tobin—for their courses on the Armenian Genocide and on Human Rights and Literature, respectively. That’s when I realized how much I enjoyed the process of teaching: leading interactive discussions with students, addressing their curious and, at times, challenging questions, learning with and from them. Soon, I was invited to teach courses that focused on the history of the Armenian Genocide, comparative genocide and the history of the Holocaust at Stockton University and Northern Arizona University (NAU). Those experiences helped me hone my teaching skills and explore and practice various styles and methods; they also proved quite educational. I was particularly keen on learning what students were more curious to study, what questions they raised in class, in their papers or during group discussions and how well their course material addressed those questions.

The Road to Gender and Genocide Studies

Soon it became apparent that questions about gendered experiences, specifically the role of female victims, perpetrators and/or bystanders, repeated and dominated the discourse in every class. Students sought to learn more about women and not just as ‘vulnerable,’ and at times ‘faceless’ and ‘nameless’ groups in perpetual suffering and need of external assistance. They raised questions about female agency. How do women exercise their agency during a time of crisis—during a war, genocide and other mass atrocities? How do they face the tremendous hardships these atrocities bring upon them and their families? How do they overcome the unimaginable physical and psychological trauma caused by sexual violence? Do they, or could they, ever heal? And then, there was another set of questions aiming to explore and understand how the male-dominated patriarchal societies exacerbated these women’s pain and trauma and paved the way for more suffering post-genocide and post-war. Why don’t we hear more about sexual violence and its long-lasting consequences when studying the history of mass atrocities? What happens to those girls and women in the aftermath of war or genocide? Are they provided the necessary means and support to heal and find peace, or are they neglected, or worse, segregated and their experience and trauma stigmatized? Are they further pushed away from the rest of society into everlasting darkness and seclusion? And finally, what can we do about it? After all, isn’t it up to us to try and change this reality?

Students’ deep, thought-provoking questions shaped my approaches to scholarship and inspired me to adopt more inclusive and novel teaching ideas and methods. Thus, when the opportunity to design and offer a new course at Martin-Springer Institute of Northern Arizona University arose, I created “Genocide and Women”—an interdisciplinary course that examined the multifaceted roles women played in genocidal and post-genocidal societies. In this class, students’ primary task was conducting a gendered analysis of mass atrocity. My role as an instructor was to create and manage a classroom where every student would feel comfortable participating in the discussion, even if the discussion topics were not always comfortable. The goal was not just to have the students entertained and engaged; it was instead an attempt to create a civil and professional environment where students would feel free to express themselves and learn from each other while discussing crucial and, at times, controversial subjects.

Focusing on women’s experiences during the Armenian Genocide, the Holocaust and the genocide in Rwanda, and learning about sexual violence and its memory in Bangladesh, Bosnia and Iraq, we analyzed the relation between gender, ethnicity, class and violence in the “Genocide and Women” class. As Elissa Bemporad and Joyce W. Warren have explained, this intersectionality “plays a crucial role in the way women experience genocide.”1 Students expressed their appreciation of the topics we discussed and the opportunity to learn about and discuss many different case studies from a new perspective, feedback that indicated the course was a success.

Discussions with guest lecturers were a favorite student experience in this class. Since they were exposed to a variety of cases, geographies and histories from the Balkans to Central Africa, from the Middle East to Southeast Asia, I invited my colleagues, educators of diverse backgrounds, to join our classes via Zoom and discuss different approaches to and methods of understanding the systemic elements of gendered violence.2 With Dr. Arnab Dutta Roy—an expert in world literature focusing on responses to colonialism in South Asian literature—students examined the role of fiction, including novels, contemporary movies and TV shows, in understanding gendered experiences of violence. They also discussed issues of agency and the meaning and role of empathy during and post-genocide. With Mohammad Sajjadur Rahman—an expert on the genocide in Bangladesh—students addressed questions of stigma connected with rape. They observed the links between sexual violence and shame during the genocide and its aftermath. With Dr. Sara Brown—the author of Gender and the Genocide in Rwanda: Women as Rescuers and Perpetrators—students discovered the complexity of female participation in the crime of genocide and in rescue and rehabilitation efforts during and post-genocide.3 Students found these in-class experiences so engaging and compelling that some asked permission to bring their friends and peers to attend the lectures and participate in discussions.

Student Analysis and Engagement

My students’ positive feedback and enthusiasm at NAU encouraged me to continue teaching this course when I joined Clark University in the fall of 2022. At the Strassler Center, I taught “Genocide and Women” as a seminar, which allowed more time for discussions and analysis. With a group of a dozen bright students, we explored the voices and perspectives of female victims and perpetrators of genocide. We addressed the role of eyewitnesses and relief workers. For students to see the subtleties and depths of the human dimension in the history of genocides and mass atrocity, we investigated the topics through personal accounts, including diaries, published memoirs, testimonies, and through novels and documentary films. These sources created a new dynamic in the classroom: students engaged closely with the text and visual material. They, for example, noticed significant differences between the accounts of male and female survivors when analyzing their testimonies. Students detected females’ willingness to speak about feelings and emotions extensively rather than focusing on factual details of the events, which was more common in male accounts—an observation that corresponds to Belarusian writer and Nobel Prize laureate Svetlana Alexievich’s view: “Women tell things in more interesting ways. They live with more feeling. They observe themselves and their lives. Men are more impressed with action. For them, the sequence of events is more important.”4

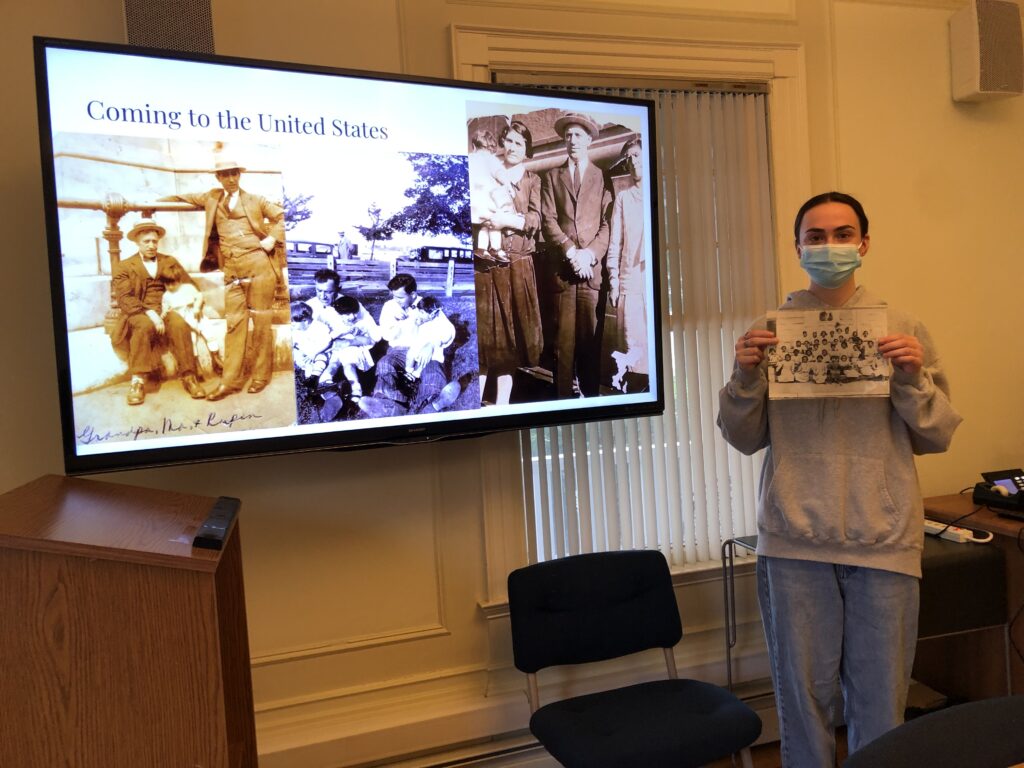

Students also showed initiative by critically analyzing and utilizing the sources assigned for the coursework. For instance, after reading the memoirs of Vergeen5—an Armenian Genocide survivor abducted by the Bedouins and later ashamed to return to the Armenian community because of her facial tattoos—and watching the documentary Grandma’s Tattoos6, one student expressed willingness to share her family history with the class. Erin Mouradian—a senior at Clark— volunteered to prepare a presentation and told us the story of her great-grandmother, Arousiag Khacherian of the province of Adana in the Ottoman Empire. Arousiag had survived the deportation to the Syrian desert and endured “horrible treatment” in a Muslim household, followed by several years in an orphanage.7 She then traveled to Cuba to marry Abraham Parseghian Mouradian—Erin’s great-grandfather. Together they eventually immigrated to the United States. Erin confessed in class that she remembered seeing her great-grandmother Arousiag’s tattoos, yet she had no idea what they meant or where they came from until our seminar. Erin’s willingness to utilize the analytical skills gained in our class, examine her family history and then share it with her peers created an opportunity for students to grasp the significance of those skills. Suddenly, it became evident that the topics discussed in class were not about some ‘distant’ and ‘faceless’ historical actors of the past. Arousiag’s story helped students relate to the victims’ experiences of trauma and survival. Moreover, they discovered how gender affected not only the experiences but also the recovery from and the memory of the Genocide.

One of the most emotional and educational experiences for the students of this seminar was the Zoom discussion led by Niemat Ahmadi—a veteran human rights and genocide prevention activist. Ahmadi survived the genocide in Darfur and was forced to flee because of her outspoken nature against the government’s genocidal attacks. To empower and amplify the voice of the communities impacted by genocide in Darfur, in 2009, Ahmadi founded the Darfur Women Action Group (DWAG).8 Generous with her time and willing to address any questions students raised, Ahmadi spoke about the continuing threats and attacks on her life and the lives of her family members even after she fled Darfur to continue the struggle for justice and accountability. Nadia Cross, one of the students pursuing a doctoral degree at the Strassler Center, later reflected on how important it was for her to have an opportunity to communicate with a female survivor and human rights activist directly. “Not only did I admire her courage and strength to pursue such work, but I also deeply appreciated that she could provide a local perspective to the women she helped, policy and lawmakers and our student group. That is incredibly unique,” highlighted Nadia.

The seminar concluded with a class conference where students presented and discussed their final papers in the classroom. The assignment entailed a comparative analysis of women’s experiences during genocide, war and other mass atrocities. Students’ presentations reflected on various case studies—from the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust to the genocides in Bosnia, Cambodia, Darfur, Guatemala, Iraq and Rwanda. Defne Akyurek’s paper titled “The Rhetoric of Denial in the Cases of the Armenian and Bosnian Genocides,” for instance, focused on Turkish intellectual Halide Edib Adivar and Serbian politician Biljana Plavšić—two influential women who were perpetrators and deniers of genocide. Presenting her thesis, Defne explained that although these female actors operated within different contexts and timeframes, there were quite striking similarities in the methods of their denial. She noticed, for instance, that both Edib and Plavšić reframed the victimized group—Armenians and Bosniaks, respectively—as “threatening aggressors.” These women also attempted “to redirect international attention to violence inflicted on the perpetrating population” and portrayed “genocidal violence as necessary or justified retribution for a perceived wrong committed against their nations.”9

Presenting their research results, students actively discussed issues tackled during the semester. They talked about women’s agency, resistance and denial, poetry and memory, and physical, psychological, emotional and social consequences of sexual violence post-genocide.

Focusing on women’s experiences during and after genocide allowed students to think about and analyze the history of mass atrocity through a novel, more complex and nuanced lens. Drawing upon primary sources and personal accounts of various actors, not only did they learn about different roles that women played in the time of crisis—as victims, perpetrators, rescuers, resisters, collaborators, traitors, witnesses, human rights activists, among others—but they also discussed the importance of culture and culturally defined roles of women, the rules historically imposed by society that affected the experience of women during and post-genocide. Moreover, interacting with several guest speakers, including survivors and activists, and engaging in thought-provoking discussions in class, students completely immersed themselves in every aspect of gender analysis of war and genocide, ultimately developing exceptional research questions and final projects.

Endnotes:

1 Women and Genocide: Survivors, Victims, Perpetrators, Elissa Bemporad and Joyce W. Warren, eds., (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2018)

2 Special thanks to Niemat Ahmadi, Dr. Sara E. Brown, Dr. Arnab Dutta Roy, Natalya Lazar, and Mohammad Sajjadur Rahman for guest-lecturing for and sharing their expertise with the students of “Genocide and Women” class.

3 Sara Brown, Gender and the Genocide in Rwanda: Women as Rescuers and Perpetrators (Routledge, 2017)

4 Masha Gessen, “The Memory Keeper. The oral histories of Belarus’s new Nobel laureate,” in the New Yorker, Special Issue (October 26, 2015) https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/10/26/the-memory-keeper

5 Mae M. Derdarian, Vergeen: A Survivor of the Armenian Genocide (Atmus Press Publications, 1996)

6 Grandma’s Tattoos, Suzanne Khardalian (2011)

7 According to Erin Mouradian, “a deal was made by Arousiag’s mother with a Turkish family and Arousiag was in the custody of a Turkish family but was treated horribly–all she ever elaborated on was that they barely fed her.”

8 Darfur Women Action Group (DWAG) is a women-led anti-atrocities nonprofit organization founded in 2009. DWAG seeks to empower and amplify the voice of the communities impacted by genocide in Darfur and to provides a platform for the international community to hear directly from those who are impacted the most by the ongoing violence in Sudan. For more, see: www.darfurwomenaction.org

9 Defne, Akyurek, “The Rhetoric of Denial in the Cases of the Armenian and Bosnian Genocides,” Unpublished Final Paper for HIST 239: Genocide and Women seminar (December 2022).

Be the first to comment