The Great War caused unprecedented calamities throughout 1914-1918 and affected the lives of millions of people – combatants and civilians – both on battlefields and on home fronts, challenging humanity. The war that ensued on the Caucasus front in November 1914 triggered enormous population movements, accompanied by massacres, violent persecutions, rape, famine, and epidemics. These population movements were the result of war and the genocide organized and systematically implemented by the Ottoman Turkish government against its Armenian subjects.

By late summer 1915, hundreds of thousands of refugees – the majority of whom were Armenians – had crossed the Ottoman-Russian border and created an immense humanitarian crisis in Transcaucasia. Russian imperial government (both military and civil authorities), state-funded and public agencies such as the Tatiana Committee and the All-Russian Unions, as well as local Armenian committees such as the Armenian Benevolent Society and the Committee of Brotherly Aid, organized and coordinated the relief efforts on behalf of over 200,000 refugees crowded in Alexandropol (Gyumri), Etchmiadzin, Erivan (Yerevan), and Tiflis (Tbilisi), among others. To reach out to various communities in all parts of the vast empire and make the voices of refugees seeking shelter, food and warm clothes heard, the state and local relief organizations deployed the power of the printed press. A number of newspapers and periodicals in the Russian Empire placed appeals in their issues regularly to raise funds and help the refugees confront this emergency.

The Bezhenets [Refugee] weekly newspaper was published in Moscow in 1915. It was entirely dedicated to the concerns and needs of refugees in the Russian Empire. In contrast to most of the contemporary periodicals, it did not offer illustrations and cartoons. Instead, it published full texts of the laws and regulations passed by the government to coordinate the life and movements of refugees. Moreover, the Bezhenets reported on the efforts of various relief committees, trying to focus the public’s attention on the urgent needs of the refugees and the importance of everyone’s participation in the assistance. For instance, the October 4, 1915 issue of the Bezhenets [figure 1] carried a column reporting on the relief efforts of the Moscow Armenian Committee, which had been sending monetary, medical assistance and clothes to the refugees in the Caucasus since October 1914. It described the committee’s substantial efforts on behalf of the Armenian refugees first in Alashkert (Eleşkirt), and later in Ashtarak and Etchmiadzin. By August 1915 the number of refugees was far exceeding the capacity of towns to shelter them, hence the condition of refugees was extremely critical. The column also included the address and the phone number of the committee’s Moscow office to encourage further donations and continuous support from Muscovites and the people of the empire. For the same purpose, each issue of the Bezhenets contained quite comprehensive lists of national relief committees – Armenian, Estonian, Jewish, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish – based in Moscow. Furthermore, the issues carried a segment “Rozyski bezhentsev” [Searching for Refugees] – a common practice among periodicals printed during the wartime – and aimed to help refugees find their lost family members.

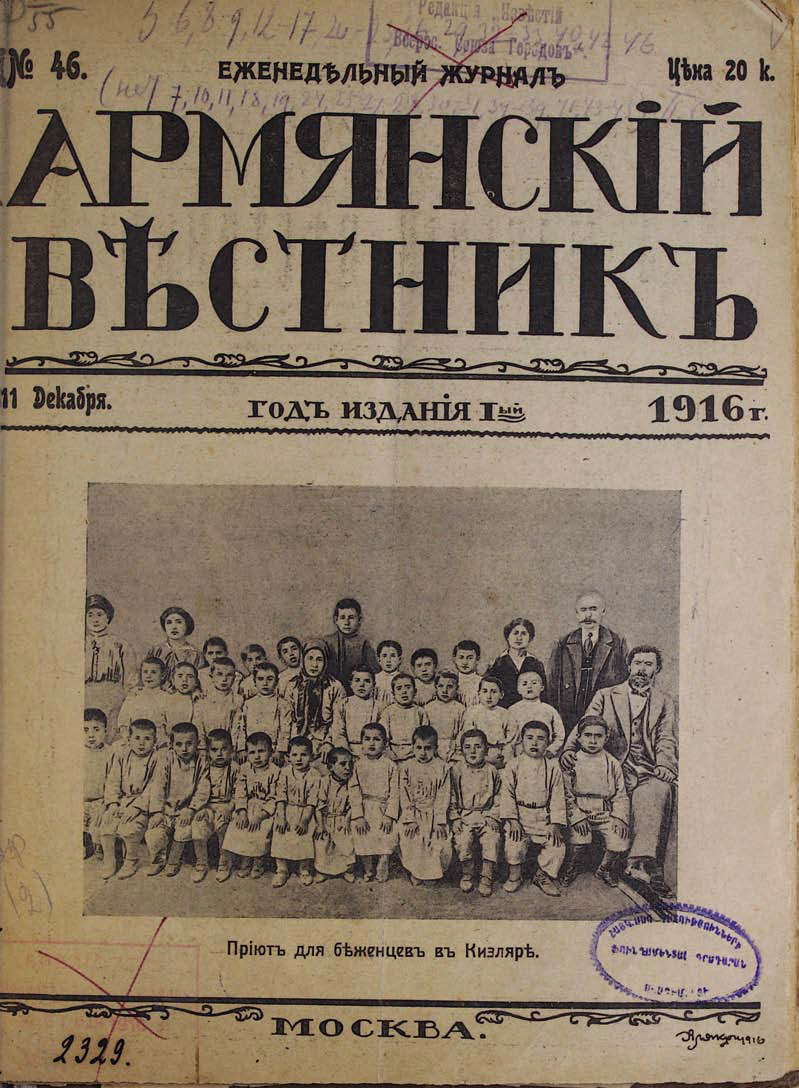

A periodical printed by the Moscow Armenian Committee starting from 1916, the Armeianskii Vestnik weekly focused entirely on the issues of displacement of and aid for the Armenian refugees in the Caucasus and the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire [figure 2]. Furthermore, in an effort to boost the fundraising the Armianskii Vestnik shed light on specific activities and operations conducted by the relief workers and volunteers.

Front page of the 11 December 1916 issue, Armianskii Vestik

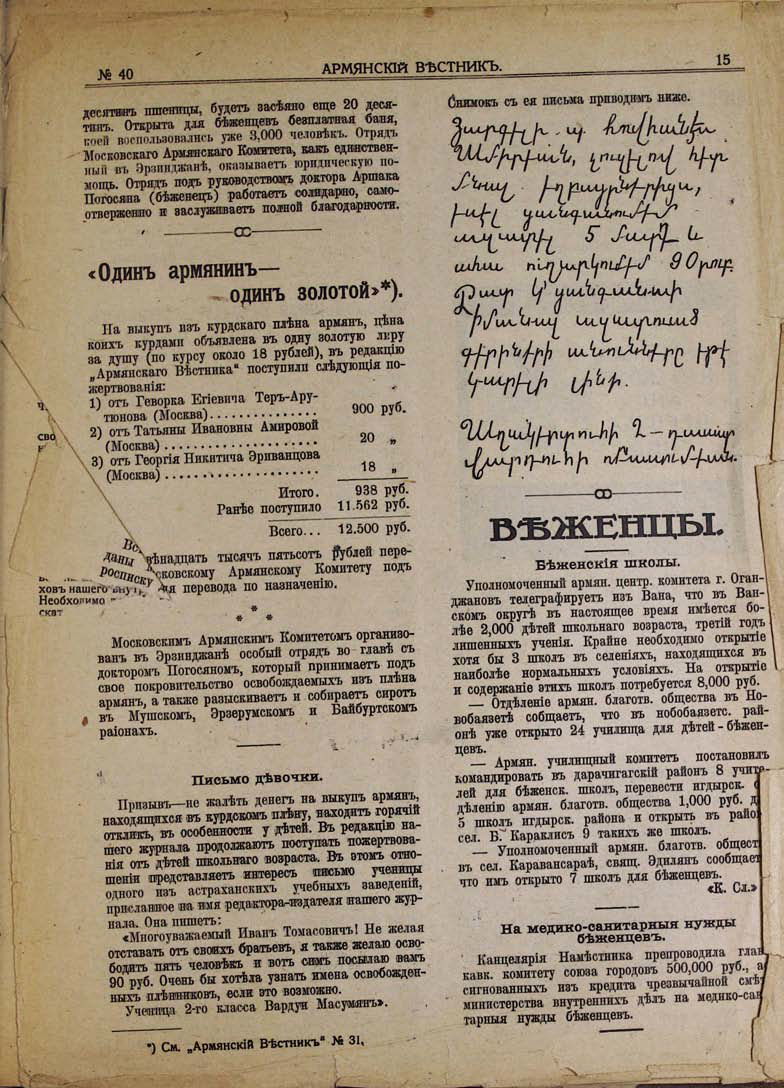

Among the weekly’s extensively covered subjects was the rescue of abducted Armenian women and children from Muslim households and the initiative “one Armenian, one [piece of] gold,” which referred to the payment of one Ottoman lira (equal to 18 rubles) for one liberated Armenian. This initiative became very popular among the schoolchildren representing communities from various parts of imperial Russia. Numerous children sent envelopes with enclosed donations to “liberate” Armenians from “Kurdish captivity.” In her letter (handwritten in Armenian) addressed to the Armianskii vestik’s editor Hovhannes Amirov, second-grade student Varduhi Masumyan from Astrakhan explained that she “wanted to liberate five people and sent 90 rubles” for that purpose. Varduhi also requested to send her the names of those liberated, if possible [figure 3].

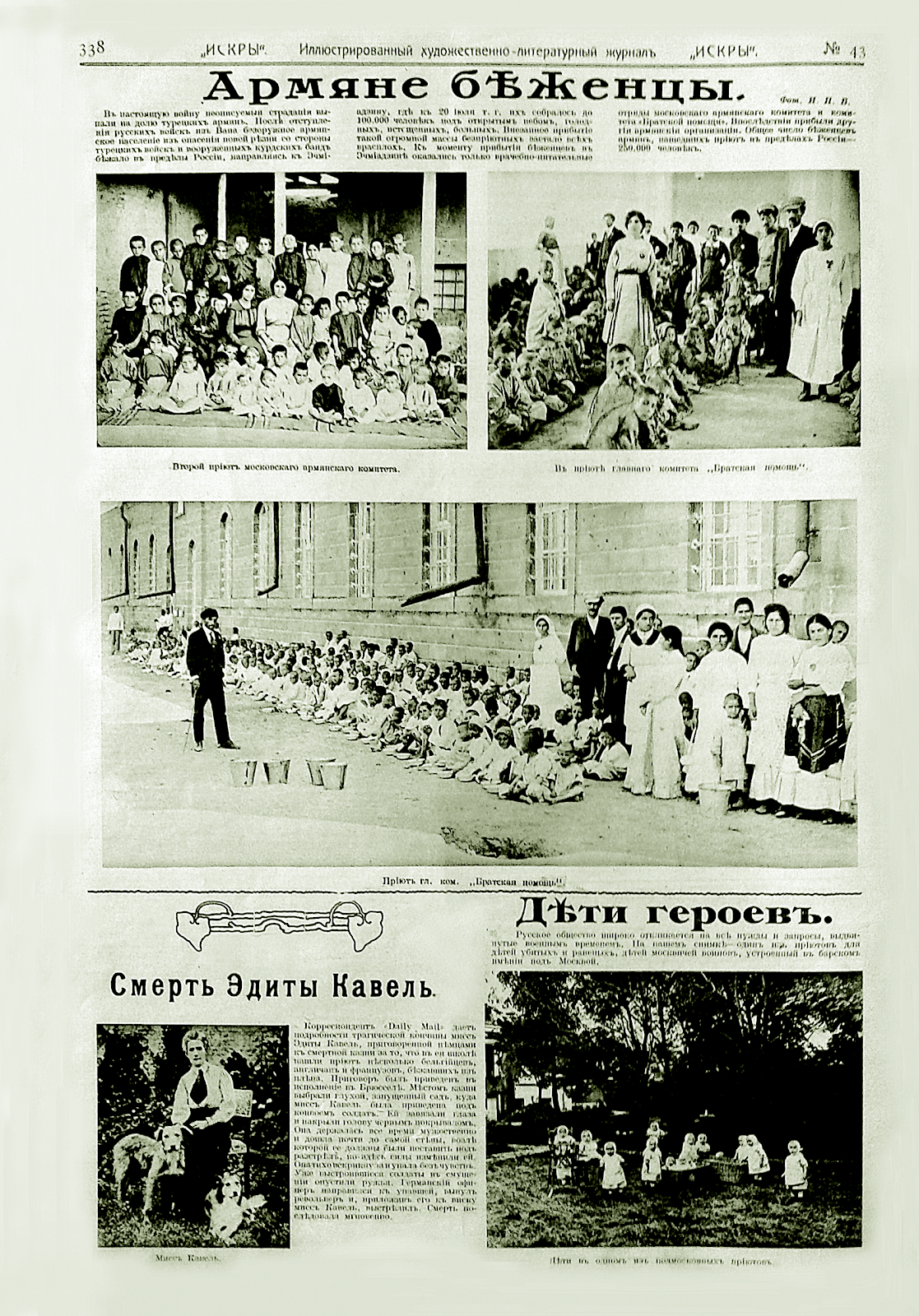

While the Bezhenets and Armianskii Vestnik focused overwhelmingly on refugees, the Iskry [Sparks] illustrated literary journal with cartoons, published weekly in Moscow from 1900 to 1917, reflected on international politics and on everyday life in the interior of the vast Russian Empire. From 1914 to 1917, Iskry actively reported on developments on war fronts and the situation in the rear. The November 1, 1915 issue of Iskry drew the attention of its readers to the Caucasus front of the Great War. The front page carried the picture of General Nikolai Iudenich – the commander of the Caucasus Army. The second page was dedicated to the condition of refugees in Transcaucasia [figure 4]. The article titled Armiane Bezhentsi [Armenian Refugees] lamented:

“The current war had incredible consequences for Turkish Armenians. After the Russian retreat from Van [July 1915], the unarmed Armenian population fearing new massacres by Turkish troops and Kurdish bands escaped to the Russian territories, went to Etchmiadzin, where by July 20th there were about 100,000 people outdoors – hungry, exhausted, and sick. The sudden arrival of such a huge mass of homeless people was unexpected. When they reached Etchmiadzin, only the medical and feeding squads of the Moscow Armenian Committee and Brotherly Aid Committee were there. Later on other Armenian organizations arrived in town. The total number of Armenian refugees that found refuge within the boundaries of Russia is 250,000.”

The article included three photographs of refugee children in Etchmiadzin. The first photo was taken at the No. 2 orphanage of the Moscow Armenian Committee, which was smaller and better funded, hence the children in that picture looked fully clothed and neat. The second and third photos depicted the orphans and their caretakers – the nurses and administrators – at the orphanage run by the Etchmiadzin Committee of Brotherly Aid. This orphanage had been under a lot of pressure because of the endless flow of refugees into Etchmiadzin and lack of necessary funds. Thus, the photos articulated the desperate condition of those tiny human beings – famished, covered in rags, lined up outside the building, waiting for their ration of meals. These at times graphic images and detailed reports aimed to awaken compassion and empathy among ordinary people of the vast empire towards the refugees in need of care and support.

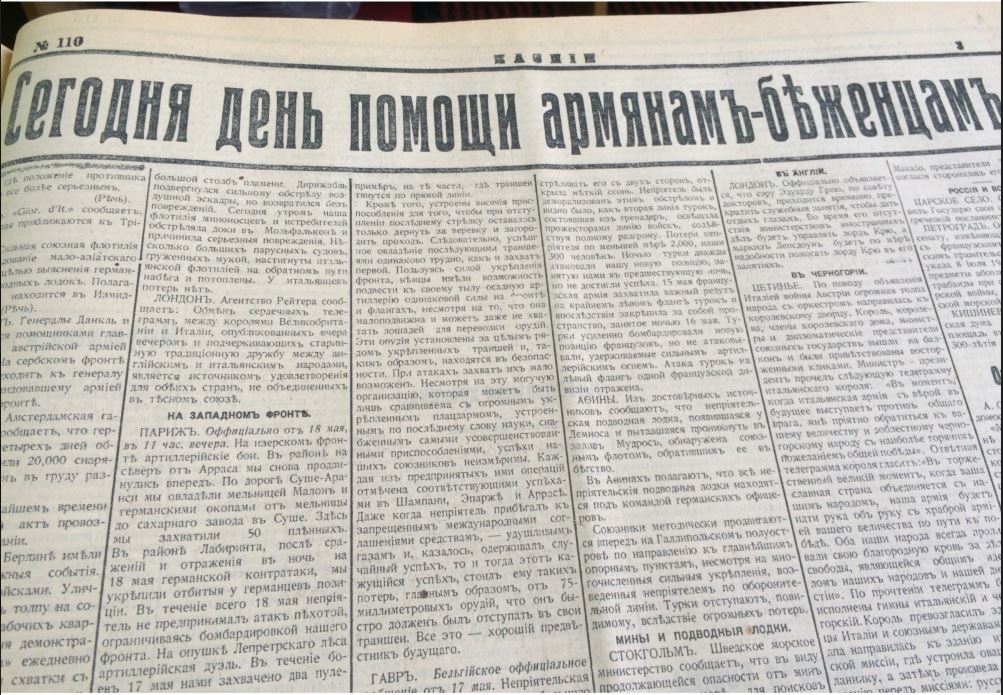

The Kaspii literary and political daily newspaper, published in Baku since the 1890s, also reported on the refugee movements at the Ottoman-Russian borderlines and their pressing needs for assistance in the Caucasus during the wartime. One of the headlines of the 21 May 1915 issue of Kaspii stated: “Today is the Armenian Refugees’ relief day,” [figure 5] and was dedicated to the fundraising campaign on behalf of the Armenian refugees in Transcaucasia.

While Russian imperial government assigned funds and organized the relief work for the Armenian refugees of the war and genocide, the extensive reporting on the condition and needs of refugees, the photographs of children and the orphanages, and the appeals to ordinary people for donations and support published in the periodicals throughout the empire played a significant role in raising awareness about and assisting the hundreds of thousands of refugees with food, medicine and warm clothes in such times of crisis.

Be the first to comment