When tragedy strikes close to home

Human beings traditionally greet the New Year by bidding farewell to the old one. We lay past experiences to rest, mature from their lessons and step forward with hope as the calendar resets. Sometimes, though, turning the page is nearly impossible — especially when tragedy strikes close to home.

The Greater Boston Armenian community is painfully aware that such a tragedy struck at its very heart on Dec. 23, 2025. It happened just as our schools were closing for Christmas break and families were preparing to celebrate the New Year and Christmas: a sudden and unexpected multi-vehicle car accident, on the corner of Bigelow Avenue and Mount Auburn Street. Many of the passengers in and around the crash were Armenian: members from the various surrounding church communities, but part of the one, united Armenian family. Most knew each other; some were even coworkers. If Watertown is the little Armenia of the East, then Bigelow and Mt. Auburn are its epicenter.

The outcome was heartbreaking. A few were physically injured, most severely John Orchanian and Anna Kupelian. Thankfully, they have since almost fully recovered. They, and many more were deeply and emotionally traumatized at the sight of what had transpired.

In John’s vehicle, two lives were instantly lost: his son, 32-year-old Arie Orchanian, and sister, 80-year-old Anie Manoushagian.

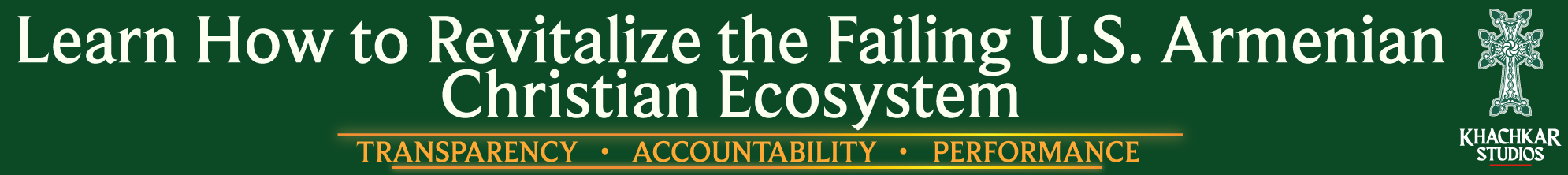

John’s wife is Digin Maral Orchanian, exemplary member of Armenian Memorial Church, and dedicated Preschool Director of St. Stephen’s Armenian Elementary School. Anie and Arie were very active and well known in their church, but Digin Maral is a familiar face to the broader community, as she has cared for most of our children.

When concerned bystanders on the scene started to contact their loved ones and share the news, everyone was in disbelief. How could life be so fragile? And until this day, even after 40 days of mourning, the dust hasn’t settled. We are left asking: how does one handle such loss and grief?

…

No two people’s situations are ever the same. Some are born into great comfort, others into even greater hardship. Some carry generational pain, others generational wealth. Physical shoes may fit many — but life’s shoe fits only one specific individual.

On the one hand, as an Armenian, I carry the generational trauma of the genocide; and on the other, I cannot disregard how I have been blessed in my own life. My recent ancestors were stripped from their loved ones, while I grew up knowing all four of my grandparents and living within a 10-minute vicinity of them all. I had realized early in my childhood that this was significant, because some of my classmates didn’t have a single grandparent around. Furthermore, though they were in a far away country, even two of my great-grandparents were alive during my childhood.

Yet, more difficult than not having is losing what we once had.

Even the youngest understand loss instinctively. I was reminded of this fact a day prior to the tragedy that struck. I had driven from Boston to Montreal to spend time with my family, and my first stop upon arrival was my sister’s home. No doubt I missed my sibling and brother-in-law, but my three nieces were the reason I didn’t head straight home to rest after the long drive. We spent a few hours catching up, playing hide-and-seek and trying not to mix the Play-Doh with the Legos.

Finally, I stood up to leave — I hadn’t yet said any goodbyes, just strolled to the foyer. My two-year-old niece ran after me and fiercely articulated, “No, Dayday” (which is Turkish for “uncle.” Despite the trauma of the genocide, many words have still endured in modern Armenian use). Her older sisters, 12 and 10, tried to comfort her by explaining that Dayday would return the next day.

She wasn’t having it; she gave them a toddler stare down and advanced closer to the door. She picked up her pink boots and sat on the floor next to me, trying to put them on. I hadn’t yet put on my boots or coat, but my heart melted then and there. She knew her uncle well because we had spent so many vacations together and were often video calling, but the physical separation had already taken a toll on her young consciousness.

…

Arie Orchanian was — and always will be — Digin Maral’s baby boy. Tragically, he put on his shoes for the next life far too early. In the natural order of things, parents wish to be buried by their children, never the opposite. When such cataclysmic reversals occur, we struggle to comprehend them. Some speak of fate. Others suggest they were essential to the fabric of heaven. Some yet offer the notion that they might have been too good for this world. These thoughts may comfort some, but they remain assumptions — attempts to soothe pain rather than establish certainty.

There are, however, two truths we know for certain.

First: The pain of losing a child is unbearable. There is nothing unChristian about embracing sorrow. Look at Christ Himself. Jesus not only believed in the Resurrection — He was the Resurrectioner (for lack of the English equivalent to յարուցանող, ‘harootsanogh’). And yet, standing before Lazarus’ tomb, fully aware that a few moments later he would command him back into life, the resurrectioner wept. He cried — not as one without hope, but as one who loved deeply.

Second: As visceral and as real as sorrow is, so too is the fulfillment of the promise of resurrection. For Lazarus, it was immediate — what we all would wish for. But for most of us, reunion will come later: either when we ourselves depart this life, or when Christ returns — whichever comes first.

Until then, we are alive. And though no one else fully comprehends the shoes in which we walk, we still have the ability to put them on, both the metaphorical and physical. And that, in itself, is an immeasurable blessing. With benediction comes duty. Our calling is to help neighbors who are struggling with their own shoes: those who cannot wear them by themselves because of illness, or those for whom even the simplest tasks have become impossible because of a serious tragedy.

…

A burning question lingers: If Jesus wept, how can a mother not?

A mother, of all creatures, who has the God-given power to give life — hence creating an unbreakable bond — yet does not possess the power to resurrect, rendering the separation unbearable!

Even with the Resurrection affirmed beyond a doubt, how does one endure this rupture until that day?

As I ponder on these questions during the coldest time of the year, I am reminded of a remarkable phenomenon in nature. In astronomy, Apsis refers to the nearest and farthest point in a planet’s orbit around its star. Aphelion is the farthest point. Perihelion is the closest.

An incorrect assumption that sometimes regrettably makes social media rounds is that winter is cold because the Earth is farthest from the sun. It sounds intuitive, but it is incorrect. The fluctuation in distance, about three million miles, is not insignificant (~3.5%), but has only a minor effect on the weather. The true cause of the seasons, as we all remember from high school physics, is the Earth’s axial tilt (23.4 degrees).

More surprising still: Aphelion does not occur in the winter, but in summer — around July. What occurs in winter, in January, is Perihelion — when the Earth is closest to the sun.

God is teaching us a profound lesson through the stars: His warmth is closest when it feels coldest, when we need Him most. Christ, the light and warmth of this world, is in the Perihelion of our lives when we enter a harsh winter, or worst still, an ice age.

As the Orchanian family, and all who carry heavy tragedies, walk through their wintertide — through the loss of the warmth of a loved one’s presence — God promises to draw nearer: to those who mourn and, simultaneously, in the presence of their deceased loved ones.

And as we remember that this tragedy occurred on the winter solstice — the shortest and darkest day of the year — we are reminded that from that very moment onward, light, though slowly and almost unnoticeably, begins to return to our lives.

Each day that passes brings us closer to that fateful day when we will be moments away from embracing our lost loved ones; as close as Lazarus was when Jesus stood in front of his tomb. And even at that moment, seconds before reunition, we may opt to weep one last time, out of grief…but surely in that instant, moreover out of joy!

Beautiful words, beautiful faith. Christ is King!

Beautiful and comforting Hyr Hrant.

May they rest in the Peace of the Lord.

Christ Has Risen.