Our penchant for division is our Achilles’ heel

During the 1992 Los Angeles riots, which led to dozens of deaths and reflected deep racial divisions in the U.S., Rodney King, one of the men victimized before the riots, made a simple plea to stop the violence: “Can we all just get along?” Sometimes, the spontaneous words are the most profound.

Most Americans watch the political conflict in Washington with disbelief, wondering how such deep divisions can ever be mended to allow functionality. Something is broken when diverse perspectives lead to actions that consciously prevent cooperation. It seems to be everywhere. Families are fractured over arguments long forgotten, impacting future generations.

As Armenians, we rightly take pride in many attributes that sustain our identity and contribute to the broader civilization. We share these realities with non-Armenians and use them to teach our children: Armenians were the first Christian nation, subjected to one of the first genocides in modern times, generally well-educated and entrepreneurial — and, of course, clannish as survivors.

Unfortunately, we are not as good at self-assessment regarding our weak points. Problem-solving and improvement begin with an honest view of our shortcomings and the solutions we can embrace. The genocide is forever embedded in our psyche, particularly in the diaspora, and has been a major factor in shaping our identity. We criticize others for not supporting Armenian Genocide recognition, especially when their own communities have faced similar atrocities.

At the same time, we are strangely silent when Cambodians, Bosnians, Darfurians and Rwandans meet the same fate as our people. It has been particularly frustrating to observe atrocities committed against Palestinians with little more than a tepid response from Armenians. We expect respect, yet do we offer it?

Our history of internal divisions is troubling. Apparently, being Armenian is not enough. Some divisions are relatively benign, such as the segmentation in the first half of the last century based on where in Western Armenia one originated. Affinity to another Armenian from Kharpert, Sepastia or Van had a positive impact — as long as exclusion of others was minimal.

Our political divisions were — and remain — fraught with controversy and retrospective sadness. While the first republic faced enemies at its borders, famine and disease, political infighting was an unnecessary distraction. After the republic was lost, political squabbles continued in the diaspora, dividing communities.

We proudly declare ourselves the first Christian nation but seem to forget what that means. Where was love and forgiveness as we split communities and treated each other with disrespect? Why do we have a tendency to do things in twos? We have two primates or prelates in every diocese in North America. Even when Armenia was on the brink of extinction, we sent two delegations to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.

There seems to be no end to our ability to divide ourselves at critical junctures. The long-standing church schism is the clearest example of our hypocrisy. What else can you call it when all that is needed is love and forgiveness to resolve conflicts? A review of our major internal divisions reveals that one of our greatest strengths — creative and diverse thinking — is often at the front end of conflicts. When egos prevail and disrespect emerges, divisions follow. How many of us in community affairs know when our personal opinions should be subordinated for the greater good?

Too often, those on the minority side of decisions work to undermine or remain inactive instead of supporting the will of the community. That is why people leave — they have been disrespected or disrespect others. It mirrors broader political dysfunction: why, if we are all Americans, are we so divided? When loyalty to a party outweighs commitment to the collective good, dysfunction thrives. Similarly, in Armenian communities, the organization often becomes more important than its mission, unnecessarily dividing us.

Our disunity has evolved, but the same mentality persists. As we moved from historic Armenian identifiers to political parties and church affiliations, a cultural veneer is now forming between the diaspora and the homeland. We should take these early signs seriously. Armenians in the diaspora must love and respect the homeland for the ideal it represents. Likewise, our brothers and sisters in Armenia should respect the courage and commitment of the diaspora.

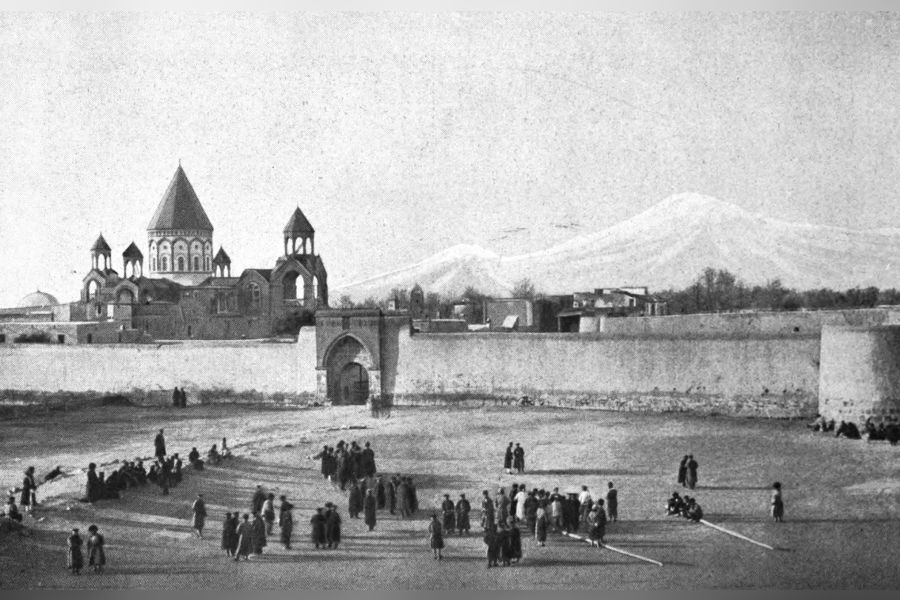

Many Armenians in the Western diaspora were disheartened this week to witness the latest escalation in the conflict between the Armenian government and the Holy See of Etchmiadzin. 37 bishops of the church made public declarations on opposite sides of the conflict. 10 senior bishops signed a document calling for the Catholicos to take a “leave” while succession is planned. This was followed by 27 bishops declaring support for Karekin II. Notably, Hovnan Surpazan, primate of the Western diocese, was among the 10, while Mesrob Surpazan was part of the 27.

Taking public sides adds little value other than political posturing. With such a schism among bishops, are we prioritizing the health of the church? A public opinion poll among the laity would only deepen the division. The senior clergy agitator in Azerbaijan must be delighted by our appetite for disunity.

We must remember that the church is run by men subject to the frailties of human life, just like anyone else. This does not excuse immorality, financial mismanagement or violations of vows. However, repentance and forgiveness are core elements of our faith. The church is a faith-based institution, not a political entity. Its internal governance mechanisms allow issues to be addressed outside state law. Taking sides and lining up for a confrontation like Roman legions does little but escalate our division.

I can understand the statement of support by the 27 bishops. It is a reaction prompted by the public conflict and the statements of the 10 bishops. Declaring their continued support is less about taking a side and more about reaffirming the due process of the church. Perhaps not all of the 27 bishops are satisfied with Karekin II’s leadership but support the integrity of the church’s structure. Working outside the defined structure, as the 10 bishops have done, clearly takes a side and contributes to ongoing disunity. If the bishops have violated Armenian law, it should be determined through the judicial processes of the Republic, with the burden of proof on the government.

All other matters should be managed internally by the church, including moral investigations, discipline and succession. Why aren’t these 10 bishops advocating for due process? The Catholicos has called for a Synod of Bishops in Armenia from Dec. 10-12 to address recent developments. This is the proper forum for discussion and will help limit further politicization through public petitions. Once the integrity of church canons has been compromised, restoration will be challenging. We learn a great deal about ourselves in times of duress. It is imperative that we gain experience rather than repeat the cycle of division.

Our history of division has often been driven by a refusal to subordinate personal perspectives to the greater good of the nation. We should ask ourselves: What will be the end point of this conflict? With one-third of the archbishops in Armenia detained, will this continue until the Catholicos chooses to resign? Under such circumstances, would the succession process follow the canons of the church or introduce an alternative? Most importantly, how will the Armenian people feel about the two most important institutions in their lives — the church and the government of the republic — once this is said and done?

Do we really believe division will lead to a stronger institution? How many upheavals can the church, already weakened by diaspora assimilation and secularism, endure while maintaining resilience? The impact of division, whether external or self-inflicted, is unique to our national church. Its role in guiding faith and identity is unprecedented. The institution is critically important to the future of Armenians, but the church must earn that role with integrity. Clergy must unite around the credibility of the church and its future. These institutions exist to serve the people, not to display drama for our dismay. Let us pray for civility, unity and respect.