My father told me that my great-grandfather Sipan Sepoyan was a clan leader in Western Armenia. My ancestors had a sense of national authority in the Armenian mountains. Unfortunately, we are currently like fish in a bowl instead of the sea. Future generations are losing the power and the sense that they have firm roots as descendants of people who have left their mark on a specific soil, among specific people. We are losing our powerful skeleton for a resilient identity like an animal breed living outside its natural habitat, kept by others to consequently end up with future generations having less defined characteristics. We are like a flower being plucked off its roots and put into a vase with water; it cannot hold its initial state from nature and maintains its bright colors for merely a few days until that which defines its beauty no longer exists.

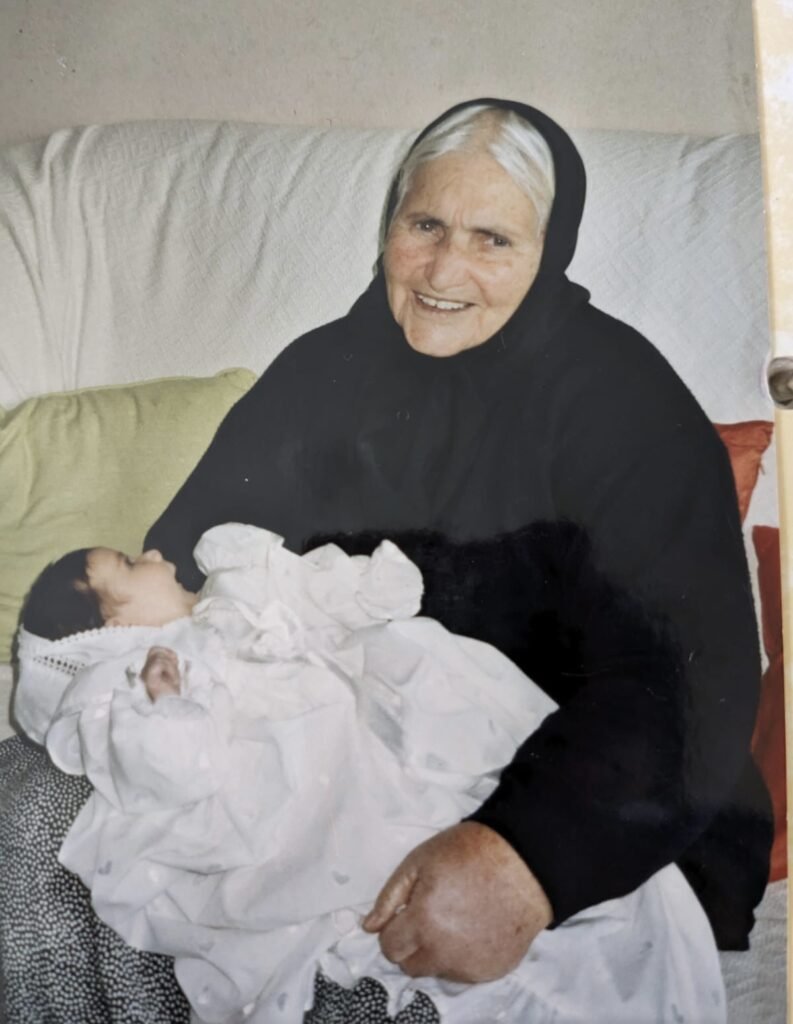

My father’s grandmother, who witnessed the Armenian Genocide, used to practice herbal healing. She was known to be an intelligent woman. When anyone in our family in the Netherlands complained about their health, she would respond, “I wish I were in our mountains; I would find the right plant to make you better.” I wish she could have returned to her mountains so that she could heal, like a root put back into its soil, ready to have a purpose again.

My maternal grandmother Armenouhi Pilavjian is a daughter of genocide survivors. She told me how her mother, Marie Minasian Pilavjian, described having witnessed a Turkish officer take an Armenian toddler by the legs and rip the poor child open. This happened when my great-grandmother still lived in Kilis, Western Armenia, as a small child before the exile. Three officers had entered her neighbor’s front yard and demanded she tell them where her son was. She told them she did not know. So they grabbed her grandchild, ripped him open and threw him on the ground. When the grandmother yelled, “Aman tornigs, aman, aman!” (Oh my grandchild, oh, oh), an officer grabbed his knife and cut her tongue off.

This was only the beginning of the traumatizing events during that period of my great-grandmother’s life. It was the beginning of the Armenian Genocide. That story was one of very few examples that voiced the trauma. Most of my great-grandmother’s stories were either abstract or comical, which does not come as a surprise, considering trauma can make one dissociate from emotions that are too extreme to handle; dissociation and humor are coping mechanisms.

My great-grandmother remembered a man who used to tell children comical stories while they were being exiled. These stories were about his life back in the village. He had been a poor man; when he broke into a house to steal bread, two people walked in, so he hid in a large clay jar. He was able to peek through a hole. The two people were the homeowner’s wife and her secret lover. When the husband approached the house, the lover hid in the same jar as the thief and was startled to see he had company. The husband, hungry for bread, began approaching the jar. His wife tried to convince him not to, but he kept walking. Realizing they would soon be caught, the lover and the thief decided to escape. On the count of three, they kicked the jar open, and hand in hand, they ran out as fast as they could. The confused wife, seeing two men run out instead of one, repeatedly exclaimed in Arabic – “Hattet wahed, talaet tneen” (حطت واحد طلعت اثنين,) meaning, I put in one and two came out. And so, the thief and the lover never went near that house again; regardless, soon after, life stopped for all Armenians there. God only knows if the man with the comical stories continued to spread cheer after the genocidal exile to the south or if he died along the way. I wonder if he did survive and where his grandchildren might reside.

My great-grandmother survived, but her wound never fully healed. Until her dying breath, she kept her deepest sorrow to herself. Her wound did not die with her. It was passed down to her children and their children (transgenerational trauma or post-memory). My siblings and I feel their complexities, which are difficult to cope with.

When my older sister Nane was in high school in the Netherlands, she wanted to commemorate the victims of the Armenian Genocide as best she could, but obstacles emerged. Usually, on April 24, Armenian students request an excused absence, while many others call in sick because they assume such a request would be denied. Nane has always asked, and it was never a problem until one year when she needed to attend a commemoration and a demonstration for genocide recognition on two separate days. The school’s board leader did not give her a day off for the protest on the 23rd. After her request was refused, Nane made an appointment to explain the importance of her presence at the demonstration. She told him that we, as Armenians, do not commemorate the victims who have fallen by merely gathering and lighting our candles; we want to raise awareness and make our voice heard because Turkey is still denying the Genocide. Otherwise, genocide will continue to take place. She referred to the book The Post-Soviet Wars by German political scientist Christoph Zürcher, who wrote that “white” genocide denotes the repression, assimilation or forced migration of Armenians from their historical land. Forced migration leads to the loss of an Armenian identity among the diaspora, which is a continuation of the Genocide (white genocide).

Nane tried to help the board leader understand so that he would change his mind and accept her request. She explained the relevance of the Armenian Genocide and the emotional value of genocide recognition and its roots; that her ancestors experienced and survived genocide and were brave enough to share their stories with their young descendants. While demonstrations or commemorations are usually held on April 24, that year, it had to be held on April 23 because parliament would be open. But the board leader of the school maintained his stance and did not show any sign of understanding. He repeatedly mentioned that April 24 is a day off, but the 23rd is not. He refused Nane’s request.

That was when she decided to say to him, “Okay, if you insist on not allowing it, then so be it. It is too important to me; I still want to be there, and I’ll just go. I am hereby letting you know that I will not be present at school for my lessons on April 23, because I will be attending a demonstration. I understand your standpoint, but I will be absent and accept the consequences it brings.” Nane would not lie about her absence; she did not want to lie to herself like others, and she thought that would be shameful toward her ancestors and her people. He responded, “Fine, then I’ll have to call the attendance officer.” Nane said, “Okay, I’ll hear when I’m called,” and she left. She went to the demonstration and the memorial; she felt proud and powerful.

She later received a letter summoning her to the school attendance officer at the town hall. My parents accompanied her. The school attendance officer asked her to recount the situation and why she skipped school. Nane honestly explained the importance of the day and what it means to her identity. The school attendance officer expressed her empathy and understanding; she said that the board leader should have given her permission. The officer recorded her absence as legitimate and ensured there will be no consequences. With her head held high, Nane left the town hall. She had been proven right, and on a micro level, she felt like, to some extent, justice had been done after all; that it was a small accomplishment in her people’s struggle and crucial for her as an Armenian that she did not attend class that day. Ultimately, the officer understood and said to Nane and, in turn, to all of us in this struggle, “You are right.”

Thank you for sharing your story. I hope it is shared through the year as we should keep these stories in our hearts and minds.

Thanks for sharing your tragic story – my heart goes out to you family. I am currently working on a screenplay based on the story of a great granddaughter now living in LA, USA. I am compiling stories to check for commonalities and differences. Would like to keep in touch. All the best for 2024 and beyond.

Thank you for sharing the stories about your ancestors. I had no idea that I would find someone with my surname at AUA. I looked at our “tohmacar” and couldn’t find your great-grandfather’s name. Which city of Western Armenia were your ancestors from?