An imposing book dedicated to the Balyan dynasty of imperial architects

The Balyans: Ottoman Architecture and Balyan Archive

The Balyans: Ottoman Architecture and Balyan Archive

By Buke Uras

Korpus, 2021

352 pp.

Hardcover, $150

Buke Uras drew on many sources in his 2021 publication, The Balyans: Ottoman Architecture and Balyan Archive. Armenian documents of the 19th and 20th centuries were translated; archives of cemeteries and churches were copied; 155 paintings were featured, 98 of which are from the Alexander Tamanyan National Museum-Institute of Architecture of Armenia, the remaining 57 are from individual collections, AGBU Nubarian Library in Paris, various Armenian, Turkish, American and European museums and state or other institutions.

Uras, an architect and writer, was born in Istanbul in 1976. He studied architecture in Rome, worked in New York, then returned to Turkey and opened his own office and taught at Istanbul’s Bahcesehir University. He has contributed to various newspapers and periodicals and currently lives in Paris.

The initiator and sponsor of this work is the HAYDJAR Association of Architects and Engineers; the project coordinators (as well as the sponsors) are Arsen Yarman and Kevork Ozkaragoz.

This book is the result of a wide-ranging collaboration. The book’s data page mentions many contributors and supporters, mostly Armenians.

In the Foreword, Arsen Yarman states that when the Balyan archive was disclosed, there was a desire to reveal its hidden realities to those interested in history. A study of that archive clearly confirms that “the Balyans, who were frequently misinterpreted as mere entrepreneurs with their designer identities remaining in the background, were actually architects actively working in the fields of both project and implementation” (p. 6). Yarman adds that very few people know that for more than a century the Balyan Amiras who built “palaces, barracks, kiosks, mosques, tombs, schools, and churches” (p. 7), contributed to the country’s industrialization and urban development, so publishing this book was a duty more than a simple desire.

Also in the Foreword, the HAYDJAR Association of Architects and Engineers mentions that the reconstruction of the mausoleum of the Balyan dynasty in Uskudar (Baglarbasi), carried out thanks to the Kirmiziyan brothers, must be considered another important event. Levon Gureghian was a colleague of the Balyans who took the archive out of Constantinople and since 1927 kept it in his “Ararat” villa (Asolo, Italy), always hoping and willing that these important documents would one day end up in Armenia. That opportunity came at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2014, when Levon’s grandson, Armen Gureghian, met Ashot Grigorian, the director of the Museum of Architecture in Armenia, and handed over the Balyan Archive to him, fulfilling the will of Levon Gureghian.

The author of the book, after presenting the general content in the Prologue, affirms that “instead of approaching the Balyan projects with a mere modern interpretation, a special effort was made to integrate the perspective of their period” (p. 13). To this end, due to Uras’ research of nearly three years and thanks to the Balyan Archive, for the first time many partially-known and never-built projects have become available: drawings of palaces and other buildings that have already been demolished or completely changed, design variants of known existing buildings, as well as Sarkis Balyan’s watercolor perspectives, which are kept in the Nubarian Library.

In the first chapter, Uras clearly affirms,

The Balyans were able to achieve an unprecedented scale in their architectural designs by adapting new typologies and introducing effective solutions to existing typologies which became increasingly complex in terms of function. Other elements characterizing the Balyan architecture are interdisciplinary collaboration, use of new materials, and organization of complex construction sites with the incorporation of innovative construction techniques and practices by closely following the technological developments of the contemporary Industrial Revolution (p. 19).

Even as they adhered to the neo-Baroque ornamentalist approaches of the time, the Balyans, he says, “while maintaining a similar monumental classicism, adopted an attitude in which traditional elements became prominent in a historical eclecticism that would later on lead to an architectural movement called Ottoman renaissance” (p. 20).

Despite the implementation of different programs, with different conceptual approaches and different styles, the author adds that the imprint of the Balyans remains recognizable due to “our psychological perception that sets up a certain connection between them.” […] That is “the spirit of space as an abstract perception. It is the majesty and grandeur that represents a giant empire spread across three continents and befits the Ottoman sultan as an exceptional art patron” (p. 20).

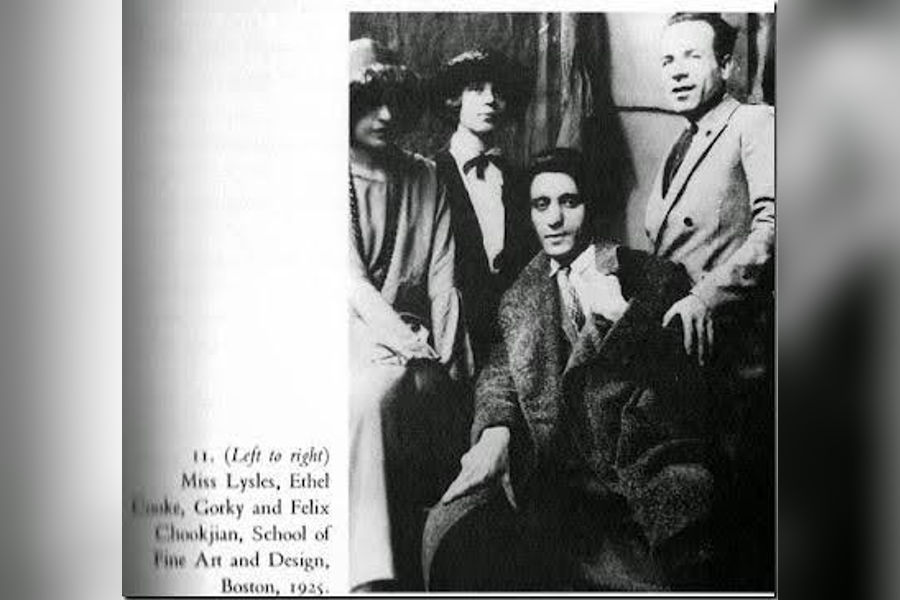

In meticulous detail, this book gives the history of the Balyan dynasty, starting with its likely ancestor Meremetji Bali Kalfa, who had a reputation as a master renovator (hence the name given to him) and who moved from the provinces to Constantinople. His descendants are known as Bali-yan, then Balyan (children of Bali). Two of them were architects: Senekerim (1768–1853), and Krikor (1764–1831) who was the imperial architect, also known as Krikor Amira (an honorary title, meaning Prince). One of the last Amiras was his son, the architect Garabed (1800–1866). The four children of the latter, who were also involved in the same field, were Nigoghos (1826–1858), Sarkis (1831–1899), Hagop (1838–1875) and Simon (1846–1894). Apart from being an architect and a talented painter, Sarkis was also an inventor who would develop construction machinery and tools. The last architectural descendant of this dynasty was Nigoghos’ son Levon (1855–1925), who due to “circumstances of the period as well as personal bottlenecks” (p. 93), moved to Paris and died there.

But the name Balyan, as the name of a dynasty of architects, persisted for some time thanks to an exceptional artist and a direct collaborator, Bali Balyan (1835–1911), who received the Balyan family name as an honor. His son Garo (1878–1960) was an architect who in 1896 (another difficult time) moved to Bulgaria and then to Cairo. There he also gained fame and designed the khedives’ (viceroys’) palaces or buildings. His son Hraztan Balyan was also an architect.

The Balyans are characterized as a dynasty that exercised collective power. They sustained cooperation within the family and across several generations, succeeded in bringing together the talents and skills of their various members, thus having a more productive career. Their end is partly the result of the weakening of that long-term cooperation.

The book also adds that it was in the days of the Amiras in general and the Balyan Amiras in particular, especially from 1820 to 1840, that it became possible to bypass the existing imperial-state barriers and repair existing Armenian churches and institutions and build new ones. This is another contribution of the Balyans, especially from the Armenian perspective.

Unfortunately, the Balyans have not left us any written documents about their architectural ideas and approaches, nor have any such documents been found, but their history is recorded through the monuments and drawings they created.

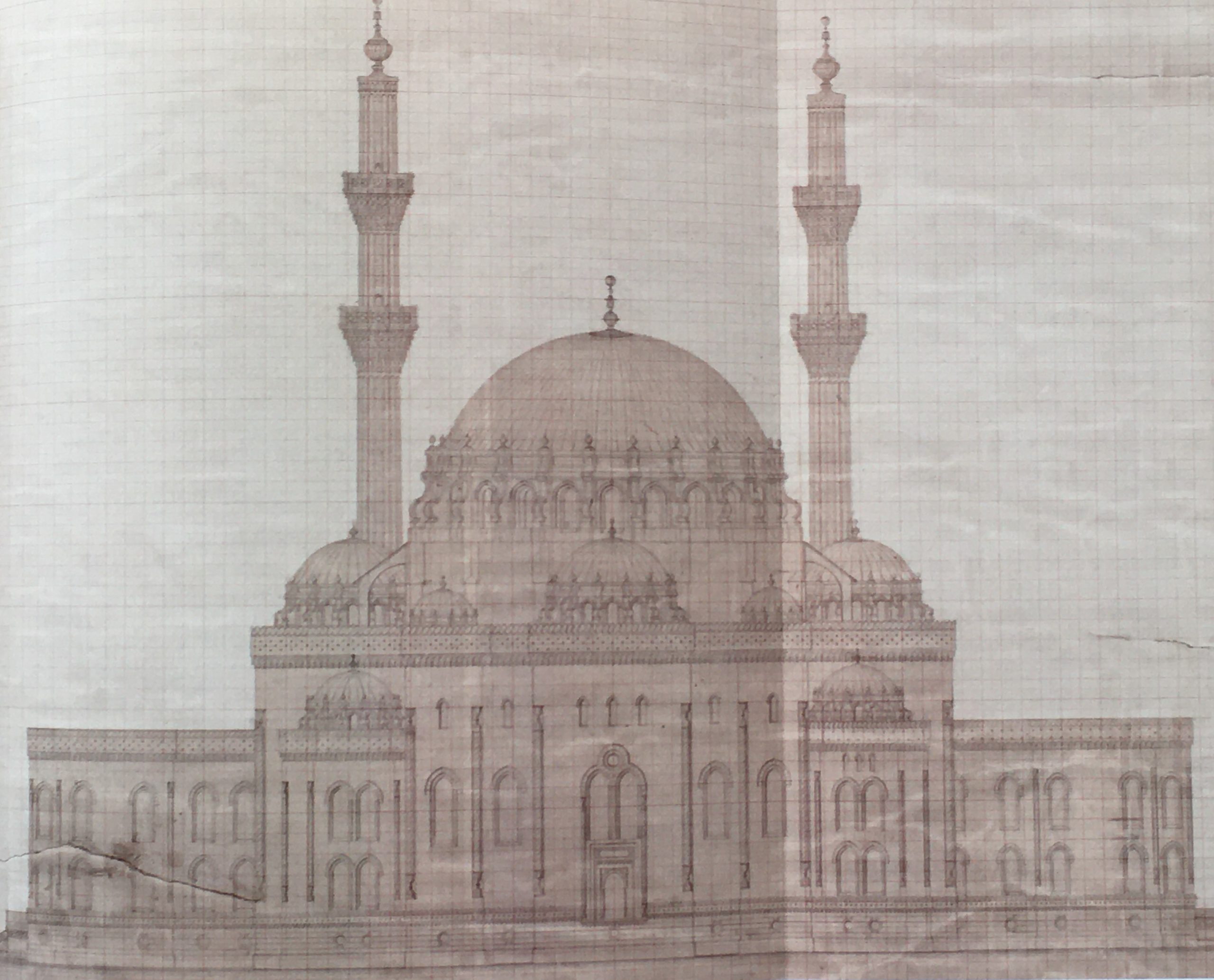

The main part of the book is the long “Balyan Archive Catalogue” chapter, about 200 pages, and even more than 200 if we take into account that many pages are double-sized and folded, which, when opened, show large drawings, sometimes up to four pages wide. These drawings are plans, facades, as well as interiors that are works of art, which reveal the incomparable talent of the Balyans in situating, designing and decorating buildings. It is here that we take a detailed look at the Cheraghan Palace, the Yildiz Kiosk, the Aziziye Mosque, the Sarayburnu Storage, the Machka Armory, the pavilions and other buildings, as well as photos from Dolmabahce palace and other buildings. We also find images of furniture or chandeliers and other ancillary items placed in those buildings, generally created by others and masterfully integrated into the architecture of the Balyans. The photo of the altar of Surp Asdvadzadzin Church in Beshiktash, taken around 1860, is also really impressive. The unbuilt Aziziye Mosque, with its planned four minarets, was to be one of the masterpieces of Ottoman and Islamic architecture.

An extensive seven-page bibliography, followed by a capacious index of people, places and buildings, completes the content of this valuable publication.

This work is a testament to the great contribution of the Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire to its development, a book which comes to enrich the work done earlier to this end. It renders a great service both to us and to the culture and history of the world.

Well done and thank you to the creators of this book. We hope that those interested will appreciate it and not only want to have a copy of it in their library, but also to distribute it, donating it to Armenian and non-Armenian schools, libraries and community centers, thus contributing to the better recognition of our nation.

A more detailed version of this book review, which was translated by AMN/VAA, may be read in the May 2021 issue of Droshak.

Here’s a link which contains some nice COLOR photos of the Soorp Asdvadzadzin Church in the Beshiktash suburb/sector of Istanbul.

http://en.besiktas.bel.tr/entry/surp-asdvadzadzin-armenian-church/