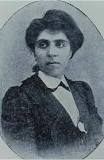

Editor’s Note: The Armenian Weekly apologizes for an incorrect image that originally accompanied Srpouhi Vahanian Dussap’s biography. The unfortunate error was brought to our attention on September 5, 2020 and was immediately corrected by Weekly staff.

In this week’s empowerment series, we introduce three incredible Armenian feminist writers: Srpouhi Vahanian Dussap, Mary Beyleryan and Shushanik Popojlian Kurghinian. At a time Armenian women were muted and their opinions unpronounced, these three leaders projected their strength, courage and fearlessness through their words, essays, journals and books empowering women with the voices they never knew they had.

Srpouhi Vahanian Dussap

Born in 1842, Srpouhi Vahanian Dussap was an Armenian feminist and the first Armenian female novelist. Her work focused on women’s rights, as she worked tirelessly for the freedom of women and against male oppression. The sister of well-known Ottoman Armenian politician Hovhannes Vahanian who was Minister of Justice from 1876 to 1877, Dussap was born into a wealthy Armenian Catholic family in Constantinople. Both were very young when their father passed away, leaving their mother Nazli Arzoumanian as their only caregiver.

Arzoumanian was a staunch proponent of education for women and as such was the driving force in making sure her daughter received an education. Dussap attended a local French school until the age of 10 and was then homeschooled by her brother. During the 19th-century girls’ schools in Constantinople were predictably non-existent past the primary level. Her brother taught her French, Greek, Italian, classical literature, science and history. He also introduced her to contemporary European writers, specifically the Romantic writers – Victor Hugo, Lord Byron and George Sand – who would ultimately influence Dussap’s own work.

A highly educated young woman, Dussap became interested in learning Armenian after meeting the famous poet Meguerdich Beshigtashlian. She began working on her first-ever literary piece in Armenian soon thereafter.

Her husband was Paul Dussap, a French musician who supported her in all of her literary goals including a dedicated space for her discussions about literary and social issues with other French and Armenian intellectuals. As an Armenian, Dussap devoted her time to helping her Armenian community in Constantinople. She was even given the title of head of the Philomathic Armenian Women’s Association (PAWA) in 1879, an organization built to train Armenian women to become successful teachers in Armenian girls’ schools in Western Armenia. After this experience, she decided to start her own series of articles focused on women’s rights, including education, social autonomy and employment. She also advocated for the Armenian Women’s School Society (AWSS), securing funds from local banks and theater performances to name a few.

In addition to her many accomplishments, Dussap wrote her first fiction novel in the form of an epistolary titled Mayda in 1878. This novel sold hundreds of copies in only a few weeks, contributing to women’s rights in Armenian literature. To further her ideologies, she then wrote Siranoush in 1884 and Araxi in 1888.

When she fell ill in 1888, she was forced to quit writing altogether; however, she continued to help the Armenian community with her charitable and educational work. After returning to Constantinople from her two-year long visit to France, her youngest daughter died of tuberculosis. Following this tragedy, Dussap tried to communicate with her late daughter’s spirit through religious mysticism during which she got rid of a majority of her archives.

When Dussap passed away in 1901, her name and archives were mostly forgotten in Armenian literature. However, they lived on in the minds of young women and writers such as Zabel Yesayan and Zabel Assadour who continued Dussap’s work.

Mary Beyleryan

Born in 1877 in Constantinople, Mary Beyleryan attended Esayan School and later became a teacher. She also continued her education in the Pera district in Constantinople. While she was a student, she began working for a newspaper known as Arevelk as a young writer.

Beyleryan became involved in the Armenian liberation movement through the Hunchakian Party at a young age. A media correspondent turned leader, in 1895 she helped organize the peaceful Bab Ali demonstrations in Constantinople to fight against the Turkish government which led to the execution of the May reforms. Furthermore, the Turkish government ordered her death sentence in absentia and she fled to Egypt.

As a writer, feminist and public figure, Beyleryan is one of the lesser known intellectuals from Western Armenia. A survivor of the Armenian Genocide, Beyleryan was an educator as well as a role model for thousands of Armenian women around the world. She began producing a women’s magazine Ardemis in 1904. The first women’s periodical in the Armenian world, Ardemis shared topics on Armenian women’s liberation. Before the periodical was published, Beyleryan’s husband, Avo Nakashian visited Etchmiadzin to ask for support from Catholicos Mgrditch Khrimian. Following the meeting, Khrimian Hayrig was fully supportive of a women’s periodical and agreed to help Beyleryan with her new project. He contributed some of his writings as well and offered to donate the profit from the publication to the newspaper.

The publication’s main focus was to raise awareness for women’s rights and education. Ardemis also promoted philanthropic activities. Beyleryan, who was the chief editor of the magazine, amazed readers then as she does today with her feminist writing and progressive ideas.

Ardemis offered women the opportunity to express themselves in ways they hadn’t been afforded before its creation. They finally had a powerful way of reaching a variety of social classes, giving everyone a chance to openly discuss topics about women’s issues. The magazine broke down borders and boundaries bringing together women from Tbilisi, Moscow, Kars, Nor Jugha, New York and Paris. Coupled with the collaboration of famous writers such as Vahan Tekeyan, Yeghia Demirjibashian, Zaruhi Kalemkarian and American journalist Alice Stone Blackwell, Ardemis delivered powerful poignant messages.

In addition to her works about women’s rights, one of Beyleryan’s beliefs was that feminism in the West did not match the Armenian reality. She argued that Armenian women needed “natural rights,” meaning the right to voice their own opinions, as well as question their role in the country’s socio-political discourse. Beyleryan shared her thoughts about the challenges of the average Armenian woman’s daily life in her editorial “A Glance Into the Past of the Armenian Woman,” where she criticized the relationship of husband/wife as well as a woman’s role in the family unit.

“Family life was hell for the Armenian in the past. She was forced to be a shadow, nothing more. It was considered shameful for a young man to speak openly, friendly and lovingly to his wife. If he dared to, those around him would call him effeminate. He would be reproached and insulted by them. If he had something important to say to his wife, he did so without looking at her face,” wrote Beyleryan.

When writer Victoria Rowe (2009), published her book “A History of Armenian Women’s Writing 1880-1992,” she recognized four main topics covered in Ardemis: women’s rights, education, motherhood and employment. She identified them as the most important issues Armenian women faced for centuries, some of which are still relevant in 21st century Armenia.

After the Young Turk revolt in 1908, which aided in restoring the Ottoman Constitution, Beyleryan returned to the Ottoman Empire to teach at an Armenian school in Smyrna (Izmir). She also worked on her own collection of writing known as Depi Ver, meaning “upward,” which was later published. She worked on this collection until her tragic death on April 24, 1915 at the age of 38. She, along with writer Zabel Yesayan, was among the women arrested alongside 200 other Armenian leaders and intellectuals at the onset of the Armenian Genocide.

Shushanik Popojlian Kurghinian

Shushanik Popojlian Kurghinian was born in 1876 in Alexandrapol, Armenia (Gyumri) and grew up in a poor family. During that time Armenia was split between two foreign powers; Western Armenia was under Turkish rule while Eastern Armenia was controlled by the Russian Empire. This compelled Kurghinian to get involved in the fight for Armenian liberation. In 1893, she joined the Armenian Social-Democratic Hunchakian Party to fight against the Turks and the Tsarists.

As an Armenian writer, Kurghinian became a catalyst in the development of socialist feminist poetry. She is well-known and praised for “giving a voice to the voiceless.” Born Popoljiants, Kurghinian was an Armenian poet and activist. She was known for her commitment to art and politics and used that to fight against oppression as an Armenian woman and member of the working class.

At the age of 21, she married Arshak Kurghinian at her family’s request; together they had two children. In 1903, she ended up in Rostov-on-Don and joined the revolutionary movements in Russia. These movements led to the creation of the Soviet Union. In 1921, she moved to Sovietized Armenia to help rebuild her country.

Kurghinian was a fighter for Armenian women. In 1907, she wrote a powerful poem called “I Want to Live,” highlighting the struggle against the male population. She believed standing in opposition of men would aid in the liberation of her people. The poem reads:

“I want to fight–first as your rival,

standing against you with an old vengeance,

since absurdly and without mercy you

turned me into a vassal through love and force.

Then after clearing these disputes of my gender,

I want to fight against the agonies of life,

courageously like you–hand in hand,

facing this struggle to be or not.”

Kurghinian is one of the most formidable Armenian female figures. Her strong commitment and passion for equal rights remain an indelible part of her legacy, as evidenced by this excerpt from her 1907 poem “Let’s Unite.”

“Enough of carrying the burden of this empty world’s grief and sorrow on our shoulders!

Enough of incessant weeping that dulls the spark in our eyes!

Enough of sacrificing our blooming youthful days to these cruel laws, neglected, defenseless between four walls, enough of letting them close the open doors!

Come, dear sister, let us hail the world and summon all our comrades.

Let’s find a solution, clear a new path unlike this low dark oppressive life.

Come, dear sister, let’s unite, let us partake in this great holy fight.

Paralyzed by imprisonment, enough of our enslaved existence with numbed minds!

Let them, our lucky men, not be so insolent in dashing forward; without us, trust me, sister, they won’t achieve any goal, they’ll fall apart!

Let’s go, dear sister, fearless, hand in hand, sacrificing all for our righteous cause, everyone is equal and worthy of the fight for the liberation’s blessed light!”

Although her famous poems were written decades ago, her timeless words continue to inspire women today. Kurghinian died in Yerevan in 1927 at the age of 51 due to poor health. She is buried in Komitas Pantheon Park.

Dussap, Beyleryan and Kurghinian together were a voice for the voiceless at a time when Armenian women did not feel empowered enough to express themselves. These brave women rejected the notion of silence and submission and projected their voices to advance their noble missions. We must not forget their names. We must carry their spirit and instill their teachings into the next generation of young Armenian men and women.

Awesome!

Thanks SO much for introducing me to these women. I look forward to reading them. I need to connect with Armenian feminism…

Who knew. Thanks for shedding light on those brave women. We still have a way to go to change attitudes.

Thanks Tvene Baronian, for bringing these powerful women to life. Great job