As a young Armenian American attending a public school in Cranston, Rhode Island, it always frustrated me that the Armenian Genocide, a part of my family’s history, was never taught by any of my teachers. I could not understand why this horrific event, which affected so many, was never mentioned in the slightest detail. After all, we studied the Holocaust in depth, analyzed wars and learned of the horrors of racism. The connection to the Armenian Genocide from all of these events and concepts was clear to me, even as a young girl. Why wasn’t it clear to my teachers, to book publishers or to the Department of Education? Or more importantly, why didn’t it seem to matter to any of them?

As I entered middle school, I was determined to educate my classmates on the Genocide if our education system was failing us in this area. I remember a particular assignment in which I had to write an essay about a part of my family’s history. It was the perfect opportunity to share my great-grandparents’ stories of survival. Everything I had learned about the Armenian Genocide and my family’s experience I had learned from my grandparents. My grandparents were first generation Armenian Americans, and although they were coming of age in a time when assimilation was key in America, they were proud Armenians and made sure to share anything and everything they knew about their parents’ and grandparents’ lives.

In my essay, I wrote about all of my great-grandparents but focused on my great-grandmother, Zartig Krikorian Goshgarian, in particular. All of my great-grandparents were victims of horrendous atrocities during the Genocide, but I always felt that if they had to be ranked, Zartig’s experience was particularly excruciating. Zartig was a young girl when the Genocide began, and her immediate family – father, mother and older sister – were murdered early on, leaving Zartig alone and extremely vulnerable on the death march to Der Zor. Zartig was kidnapped and enslaved by Muslims and wound up in Aleppo, Syria. She endured emotional, physical and sexual abuse at the hands of her captors. Some may say it was sheer luck, and others may say it was the grace of God that saved her one fateful day at the bazaar. Her older cousin had survived the Genocide and was looking for family and friends. He just happened to see Zartig at the bazaar and helped her escape by first bringing her to a local orphanage for safety and later taking her to America – to Providence, Rhode Island to be exact – to start over. When my teacher read my essay, she decided I needed to share it with the class. It was the first time most of them had ever heard about the Armenian Genocide and one even asked me, “What’s an Armenian?”

A few years ago I found a copy of that essay that I had typed up on my word processor; the last line really got to me. I wrote, “I will make sure my children learn about the Armenian Genocide, and hopefully by the time I have children, the Genocide will be part of their school’s curriculum.” Rereading that sentence was especially moving for me because I feel as though my life has come full circle in some way. After graduate school, I became a teacher and now a school district administrator. As an elementary teacher I always struggled with wanting to teach about the Armenian Genocide, but not having the tools or resources to do so that were appropriate for younger students. Aside from my career, I consider myself a Genocide education activist through my work with the ANCA and more recently, the USC Shoah Foundation. As an adult, I’m still determined to support others with teaching about the Armenian Genocide, and it is promising to see that several U.S. states have incorporated the Armenian Genocide into their teaching frameworks. History textbooks have also begun to include more accurate information on the Genocide, which is a good start but we still have work to do. Plus, all of this is happening at the high school level, but younger students are definitely capable of learning this important history.

How could I make this history more approachable for younger students without diluting it?

Wheels were turning in my head for a long time. How could I make this history more approachable for younger students without diluting it? About four years ago I attended an ANC presentation in Orange County, CA by Missak Kelechian all about the work of Near East Relief. I thought I knew a lot about the contributions of Near East Relief in the aftermath of the Genocide, but I quickly realized I hadn’t had any idea about the tremendous scope of their work. In fact, this was the first time I had heard of child actor Jackie Coogan’s involvement in America’s first organized international humanitarian relief effort, and I was blown away. Here was a child, very aware of the atrocities of the Armenian Genocide, who used his celebrity platform to make a huge difference. It was at that moment I knew that Jackie Coogan and Near East Relief were ways to bridge the gap for young children. Jackie, in particular, was an inspiration, and his story could show students that anyone, no matter how young or old, can make a difference in the world.

I ruminated on these ideas and began my research phase. I continued to learn about Jackie’s work with Near East Relief, but I also began to study children’s books on the Holocaust at my local public library. I analyzed the story lines, the structure, how a difficult event was introduced. Most of the literature I encountered were picture books on elements of the Holocaust. I found over 70 Holocaust children’s books in my research in which authors focused on the Holocaust in developmentally appropriate ways—gentle enough, but still powerful. Some of them were familiar to me as my own elementary teachers had shared them with me when I was a child. I also couldn’t believe that while there were over 70 children’s books on the Holocaust, there wasn’t a single children’s book in print on the Armenian Genocide. Anything I found on the Genocide was appropriate for eighth grade or higher.

As I began to draft my manuscript, I knew it would have two main characters – Jackie Coogan and an Armenian orphan based on the life of my great grandmother, Zartig. I drafted and revised for a long time before I ever felt comfortable sharing the manuscript with others for feedback. Sharing something so personal and important to me was a big hurdle to overcome, but it got easier with time. Eventually I reached the point of sending it out with the hopes of finding a publisher. One time a literary agent responded to my query with one sentence: “This is not essential history.” It broke my heart that a human being would have that reaction to my manuscript, to my family’s history, to a major human rights violation that was the archetype for subsequent genocides. It brought me back to my elementary school days when my culture and history were not validated. It also made me realize that besides being a culturally relevant text for Armenian students, my project was twofold. I also wanted this book to be a “window” for non-Armenian students into a history that was definitely relatable and to which they could make connections.

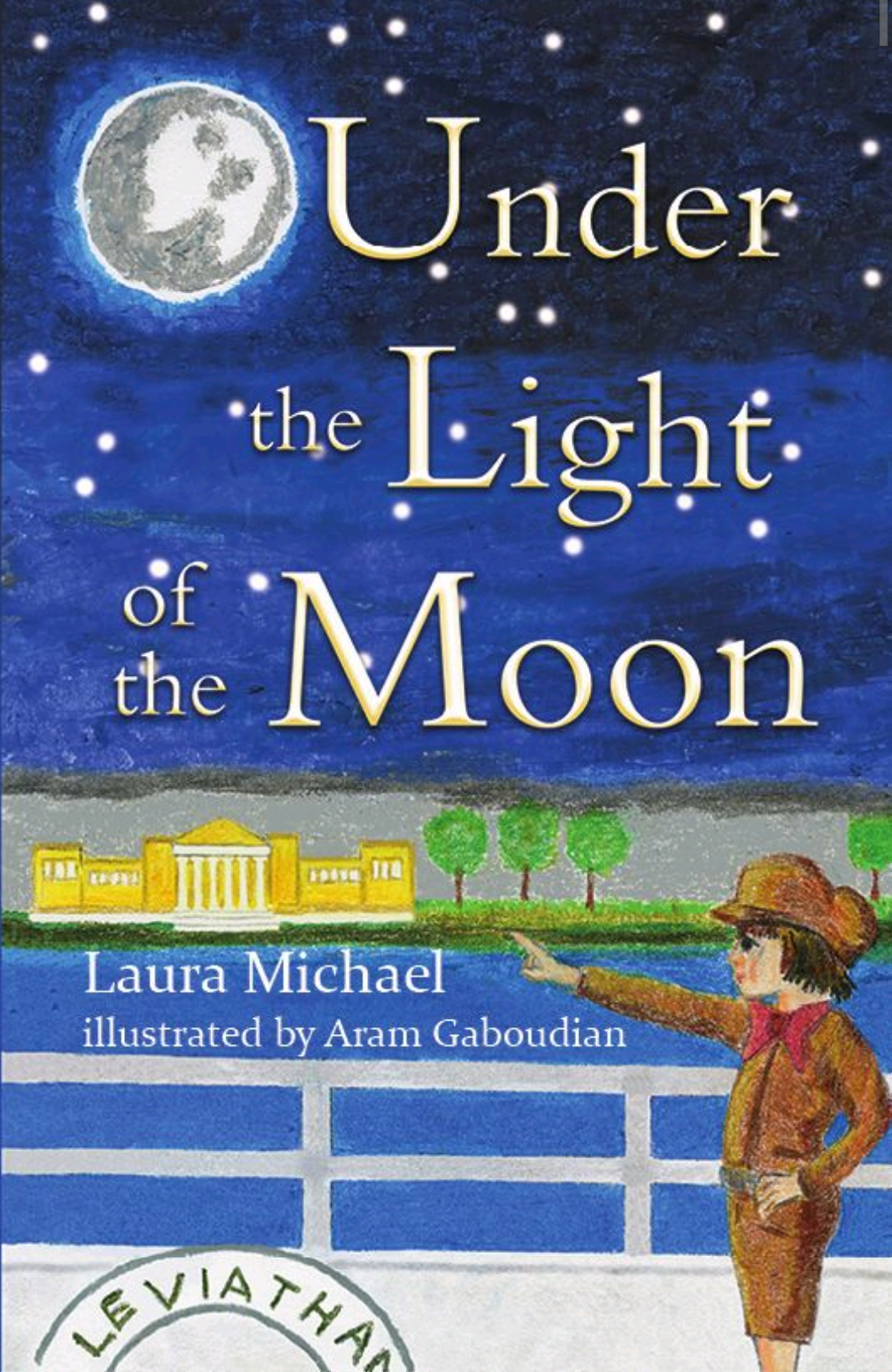

In June 2017 shortly after receiving that curt email response, I took a break from sending out my manuscript and instead ventured off on a pilgrimage to Western Armenia to walk the lands of my ancestors and hopefully find the former homes of my great grandparents. It was a successful mission in the sense that we not only found the locations of two family homes, but it renewed my conviction to get my book published. When I returned home I did find a publisher who allowed me to maintain creative control of the whole process; that also meant being actively involved in finding the right illustrator, who ended up being my husband, Aram Gaboudian. It’s been so meaningful for us to collaborate on this project, especially because the Armenian Genocide is so personal for both of us.

Under the Light of the Moon was officially published in June 2018, and it’s been a whirlwind ever since with many school, community and bookstore presentations and signings across the United States. It is also very exciting to announce that the Glendale Unified School District in California has adopted Under the Light of the Moon as part of its elementary curriculum and has acquired class sets for all 20 elementary schools. As an author on a mission, I’m really proud of these milestones for Under the Light of the Moon, but I still believe there’s a lot more work to be done. While I am up for the challenge, I hope that others are also inspired to write more children’s literature on this important chapter of both world and American history.

Under the Light of the Moon is available for purchase on Amazon and at Barnes and Noble.

To schedule a presentation or signing by Laura Michael, please contact laura@lauramichael.net.

Dear Laura,I can not express adequatly my appreation to you for your exceptional devotion to bring the Armenian Genocide at elementary school level as a third generation Armenian/American. Thank you.

My fathe was born in Marash and my mother in Antab Turky. My father in 1916 was recruited in the Ottoman Army and sent to Palestine to fight the British forces of General Alamby. He was 23 married with and had a 2 years old son when he was sent to Palestinian. In late 1918 WWI came to an and Turkey was defeated. Immediately, my father returned to Marash to join his wife, child, perents & siblings. Unfortunately, accept for one brother no one else was arround to be found. Broken hatred and alone he returned to Jerusalem to start all over again. I am his son from a second marriage. This is a typical story about the faith of 1.5 million Armenians slaughterd at the hands if the Ottoman Empire. Your desire to bring awareness of the Armenian Genocide at school level is perhaps the best way to pepetualize the memory of the victims. Thank you.

Sebu Tashjian

Former State Minister

of Armenia 1992-1996.