Special to the Armenian Weekly

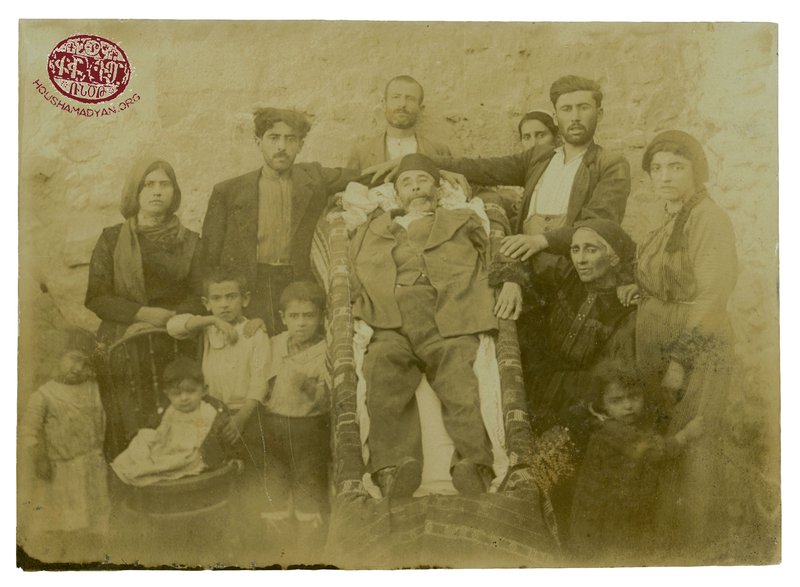

It’s undeniably a haunting photograph, no matter who you are. Taken sometime in 1918, in Al-Salt in what is now Jordan, it depicts three disheveled young men, 1,000 yard stares on their stubble-covered faces; three women—two young and one elderly with sad eyes—and a number of small children surrounding the body of an old man who lays in a simple box coffin.

But the image’s surreal contents are amplified for me. The name of the dead man is Bedros Peltekian, and I am his great-great grandson.

I had only seen one photograph of Bedros (in fact, I had only seen one photograph of his son, Sahag, my great-grandfather, as well). Bedros’ photo was published in a yellowed Armenian Life Weekly newspaper from Aug. 2, 1991, that my parents kept on a bookshelf in our home. In that photograph, a very alive Bedros, wearing a suit and fez, stands amongst a number of other similarly dressed, official-looking men. In the caption for that photograph, Bedros is titled “pasha,” the yerespokhan [parliamentarian, or deputy] of Adana Vilayet. To this day, my family still refers to him as “Bedros Pasha.”

Of the 20 or so men in the image, only a few have names listed besides Bedros Pasha—he is easy to find, as the number “1” is written above his name—including another relative whose name is simply given as “yerespokhan Balian” (there is a 3 above his name). But it’s the man with the large handlebar mustache and sword, seated in the center of the picture, directly in front of my great-great grandfather, who is the most notable.

His name was Djemal Pasha and he was the governor of Adana Vilayet. He happened to also be one of the chief orchestrators of the Armenian Genocide—the systematic killing of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire—which, one way or another, led to my great-grandfather’s eventual demise.

It was no coincidence that Bedros was standing close to Djemal, according to my grandfather, the two men would “sit on pillows, elbow to elbow,” the Ottoman style of sitting. Was it just out of formality, or did they sit that way because they were they friends? I suppose I’ll never really know, but either way, this odd photograph is the only record we had of Bedros—until recently.

In Nov. 2014, we suddenly had access to a collection of old family snapshots, including two more with Bedros, thanks to a cousin in Lebanon who submitted a number of photographs from her late-father’s (my great-uncle’s) collection to the website Houshamadyan, a website whose work documenting the lives on Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire has, in effect, created a kind of digital Western Armenia.

The disturbing “death” photograph was one we found on Houshamadyan. This photo confirmed what we knew before, but placed faces and emotions to names that we had always heard. It told us that Bedros lost everything and died far from home. This treasure trove of historic family photographs led me to want to learn more about that part of the family, which nobody seemed to know much about.

While some of the family members had been identified on Houshamadyan’s site, some were mislabeled or did not have names listed at all. My father and I studied the photographs and the captions and were able to piece together who was who.

Then one day, I Googled “Bedros Pasha Peltekian” and discovered a book, Sacred Justice: The Voice and Legacy of the Armenian Operation Nemesis by Marian Mesrobian MacCurdy. The book is a piecing together of memoirs from the author’s grandparents’, which details their involvement in Operation Nemesis, a clandestine campaign carried out by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) to assassinate high-profile Ottoman officials who implemented the Genocide.

Apparently, Bedros, along with two other prominent Armenian men (one of whom was the author’s great-uncle), were blamed for the Dortyol Rebellion that took place in 1909, as a response to the Adana massacres. Bedros and his colleagues were sent to a prison where they were tortured, and set to be hanged. At the last minute, the execution was called off, due to protests by influential Armenians in Constantinople.

Bedros Pasha survived for another nine years. Perhaps his status as a government official and his son Khatchig’s role as a prominent Constantinople lawyer, played some part in this. But even if that was the case, it was short lived. My grandfather told me a story where Djemal Pasha confronted Bedros just before the numerous massacres of Armenians evolved into a full-blown genocide. Djemal gave Bedros a warning, telling him that “We are going to start killing Armenians. If you convert to Islam, you will be spared.” My great-great grandfather refused, stating, “How could I live with myself knowing that my friends and family were killed?” Bedros and his family were deported, and somewhere along the way, he died.

Had Bedros taken up Djemal on his offer, I wouldn’t have been born. He could have converted to Islam, survived the genocide, and potentially lived to a ripe old age. But he stuck by his principles and suffered because of it, eventually losing his life. If this had happened, it’s possible that my father would have been born, but he wouldn’t be the man I know today: Culturally speaking, he’d be Turkish, whether he knew he had Armenian roots or not.

A hundred years ago, a photograph was taken of a grieving family surrounding the body of their patriarch—a man who was a father, a husband, and a grandfather. I don’t know why this photograph was taken all those years ago. I do know that “Victorian death photography” was not uncommon in the West at that time, in which photographs were taken of recently deceased individuals surrounded by their families. Perhaps my ancestors had the same sort of idea in mind?

Whatever the intention, today, this obscure photograph, taken all those years ago, in a very different world, connects a great-great grandson to his family history.

Thank you for posting this image and providing us with the story behind the family and the photo.

No matter how one slices it, the Armenian Genocide was an absolute atrocity of epic proportions and I only wish the world would acknowledge the occurrence.

Once again thank you….