Tragedy and Triumph: Berklee Announces New Scholarship for Armenian Musicians at Show Featuring Tigran Hamasyan

Special to the Armenian Weekly

BOSTON (A.W.)—The 10th annual Berklee Middle Eastern Festival marked a celebration of progress triggered by tragedy. The discrimination many Middle Easterners and Arabs faced post 9/11, prompted Beirut-born Armenian American Christiane Karam to dream up the annual festival. The aim: To remind the world of what Middle Eastern culture has to offer.

This was a theme throughout the night—prior to the festival, a reception announcing a special scholarship in former Berklee College professor David Azarian’s name. “This story starts with my dad coming to the United States, he ended up extending his visa, he came on a relief tour for an earthquake that hit Armenia,” said Christina Azarian, daughter of the jazz pianist, as she described the program that will bring over students from Armenia to Berklee to advance their music education.

At the reception, an assortment of Armenian community members mingled: the architect behind the Armenian Heritage Park, dancers from the Sayat Nova troupe, members of the local Armenian National Committee (ANC) and the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF-YOARF), and world renowned jazz pianist Tigran Hamasyan. Last year, Hamasyan was headliner at the festival, a concert that had Berklee students rocking out to Komitas. “That was the longest concert of my life,” Hamasayan remarked in a speech at the reception. “The ensemble put together… pretty much my entire life’s repertoire.”

Hamasyan is working with Azarian to shape the scholarship program, an effort that aims to build a bridge between the musicians of Armenia and the world’s largest independent college of contemporary music. Hamasyan highlighted the fact that, although he was encouraged to pursue a musical career, most in Armenia are not as fortunate: “In a way I’m lucky that I grew up in a family that was supportive of jazz and music, but a lot of those talented kids in Armenia don’t have that guidance and support,” Hamasyan noted.

“I’m here right now is mostly because of my uncle because he knows that I love music and he actually took care of me early on… I remember…the Soviet Union collapsed, and a war started, and the earthquake happened, and we didn’t have any electricity. My uncle was a huge jazz fan, and he would take me in his car for rides and just play me some Herbie Hancock,” he said.

Hamasyan will be working with Azarian to ensure the scholarship provides Armenians access to the support, resources, and expertise Berklee provides—helping the musicians of Armenia further their musical education, exposing them to greater musical diversity, and fostering their growth as musicians.

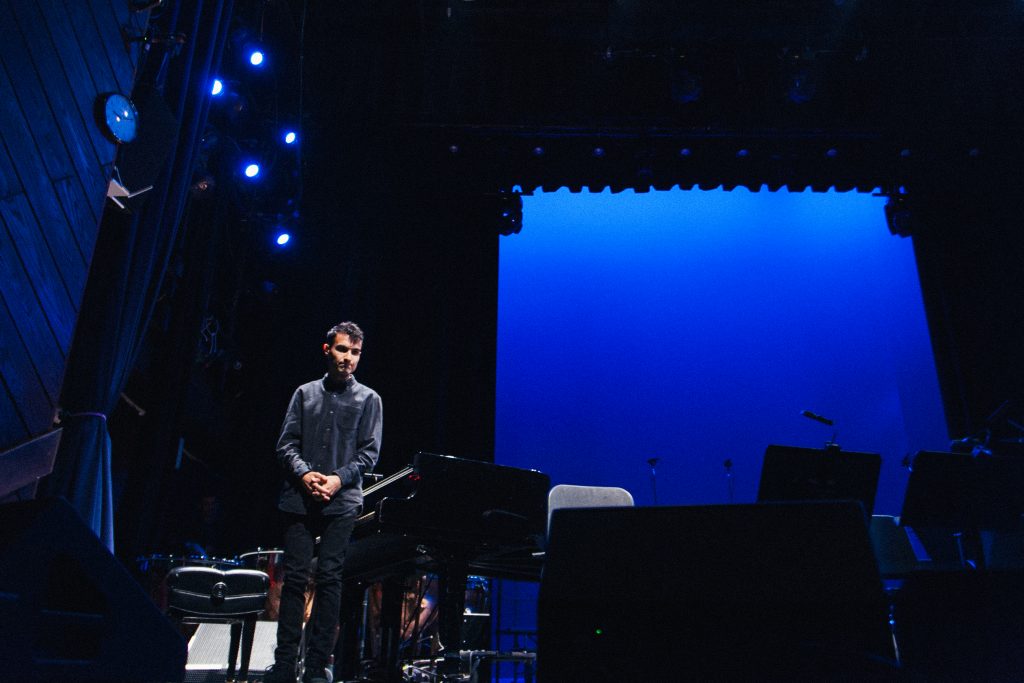

Less than an hour after Hamasyan shared his story, he came onstage to reveal what had come of all of those soundtracked drives around the neighborhood. The stage was cluttered with music stands, microphones, and seats—throughout the night, the stage held a student choir, a capella group Women of the World, a mother and son duo Amal Markus and Faras Zreik, a small orchestra, and many others. So, unlike the previous year, Hamasyan wasn’t center stage. The piano was tucked into a corner, and though the instrument and the pianist were both illuminated, it became clear the spotlight was on the invisible: the sound itself.

Hamasyan’s performance was like watching a magnificent, broken cuckoo clock. Broken, not because of missteps or mistakes, but rather, because he captured the heightened anticipation that comes with not knowing when the clock will strike. At times, he would hold back for a breath, freezing his outstretched arms mid-air, a brief silence that would produce gasps from the Berklee jazz students who knew the exceptional skills necessary for the sudden pause and the parts of the song that it separated. Occasionally, you could hear Hamasyan clicking his tongue, a metronome that counted out rhythms in time signatures the majority of the audience could not keep up with.

The night closed out with the Vadim Neselovskyi trio that—to the untrained ear—could best be compared to the Vince Guaraldi Trio, the jazz musicians behind the soothing soundtrack for A Charlie Brown Christmas. The pianist often jumped from note to note, as if each note had a tremolo, a rapid trembling than danced with the delicate hi-hat cymbals, and the booming plucking of the upright bass.

“Make music for the world you want to live in,” advised Roger Brown, President of Berklee, as the festival came to a close. Certainly, that night we saw our fellow Armenians—Hamasyan, Azarian, and Karam—come together to do just that. But these musicians also came together to do much: by creating a festival and scholarship they are lending their voices and creating new spaces so that others, too, can have an opportunity to make the music that will help build a world we all want to live in.