Special to the Armenian Weekly

Feb. 27 marks the 30th anniversary of the Sumgait pogrom—the targeted attacks on the Armenian population of the seaside town in Azerbaijan, during which widespread looting, rape, and murders ravaged the Armenian community and left up to 200 dead.

The Sumgait pogrom also marked the beginning of the violent stage of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan—a conflict that, three decades later, remains unresolved.

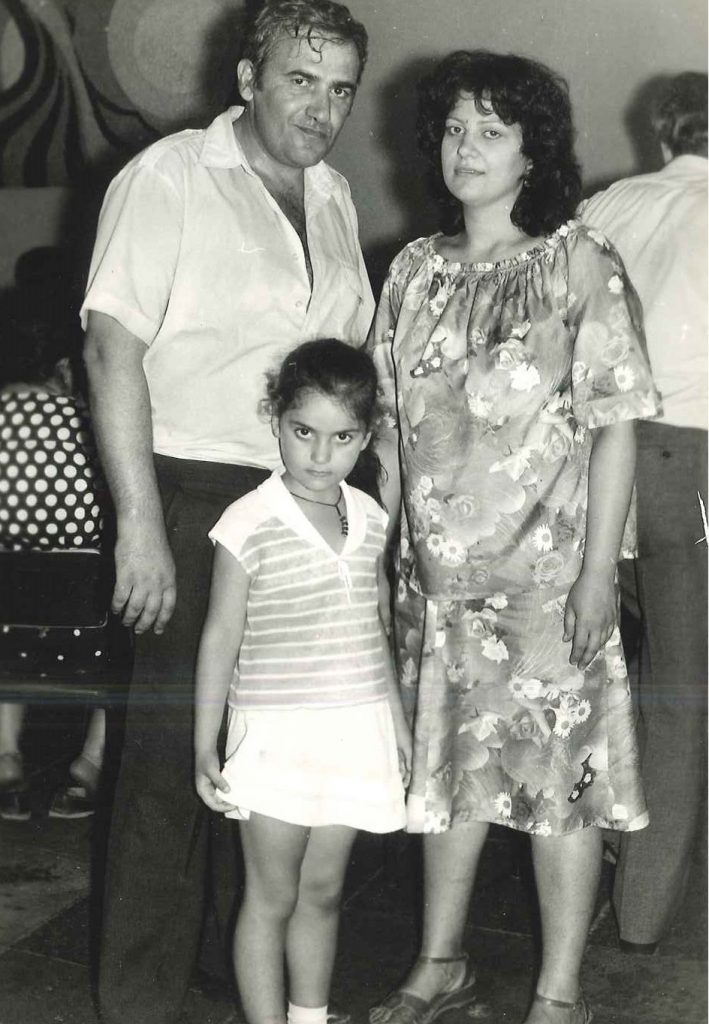

Less than two years after Sumgait, another pogrom against the Armenians civilian population began in Jan. 1990, in the Azerbaijani capital Baku. Between Jan. 12-19, 1990, hundreds of Armenians throughout the city were beaten, tortured, killed, and up to 200,000 were expelled from the city for good. Anna Astvatsaturian Turcotte and her family were among those, who were exiled from their homeland.

The following is an excerpt from the book Nowhere, a Story of Exile, which was based on Turcotte’s diaries. The excerpt is followed by the author’s recollections of that day, 30 years later.

***

March 14th finally arrives. Many people come to visit us, making themselves at home in our garden. They are relatives, friends and neighbors. Papa is preparing the meat and vegetables for the shashlik. Mama carries plates of different dishes and salads up the stairs to the garden. It is a little windy, but it doesn’t bother anyone because wind is a given feature on any occasion in Baku.

Mama lets me wear my hair down, which I never do; it is always in one thick, long braid down my back. I feel like an adult.

Uncle Novik’s family is there, his daughters are my favorite cousins, because we have become so close having lived together for eight whole years. Many relatives from both of my parents’ sides keep piling into our garden. My parents’ friends also show up. To me, they are like aunts and uncles because they are as close to us as relatives.

My cousin Lena, the daughter of my father’s cousin Tolik, is exactly my age. We are good friends.

Uncle Tolik’s mother is my Grandfather Yegishe’s sister. Her name is Maria and she is very short and old. Her hair is long and gray. She braids it and puts it in a bun, then hides it under a scarf. She reminds me of Grandma Tamara, even though she looks nothing like her. But there is something of Grandma Tamara in her. Both women are Armenian and were old friends, when Grandma was still alive. They speak Russian with a distinct Armenian accent. Their clothes—especially the dark cotton scarves, tied in the back of their heads – are worn in the same style as by most elderly Armenian women.

I wait for my Uncle Tolik, his daughters and Aunt Maria, as I call her. Everything is ready for us to sit down and celebrate.

“Where are Uncle Tolik and Aunt Maria? Weren’t they going to come?” I ask my mother.

“No, jana (sweetie in Armenian),” she answers, “Didn’t you know that they moved to Russia?”

“No, I didn’t know,” I answer in total surprise, “No one told me, where did they go?” I am not aware now that Uncle Tolik and his family, including his mother, Aunt Maria, would be the first of our clan to leave Baku.

Later I learn by listening in on the adults talking why they are the first to leave. Uncle Tolik is an engineer in a highly industrialized city in Azerbaijan, Sumgait, putting in a few weeks there and coming home to spend some time with his family, then back to Sumgait, which was right up the coast of the Caspian Sea, and so on. Around February, when he goes back to Sumgait to work, he sees something that changes his life forever. The streets are full of rubble with the remnants of things laying everywhere, like piles of furniture and clothes. He arrives there right after the lynching of Armenian residents of the city. He remains in town for a few days and hears eyewitness accounts of the massacres. Later, when he relates these events to my parents, it all sounds unreal. It couldn’t be happening to us, here, in this day and age!

The terrifying story that lingers in my mind’s eye is that of a teenage Armenian girl who is thrown out of a third-floor balcony after being stripped of her clothes and repeatedly raped. Still breathing, laying on the street, she is beaten with iron rods by the Azeri mob and her broken, naked body is set on fire to the cheers of the enraged crowd.

“The worst thing about this was that the Soviet Army that was supposed to protect Armenian families in the city from these rioting mobs, stood and watched people being robbed, humiliated, thrown out of their houses, beaten, raped, burned and killed.” Uncle Tolik tells my parents right before his family leaves the city. “The massacre did not end until late in the morning.”

After the mobs are brought under control, from his office in the Kremlin, Mikhail Gorbachev lies to the people of his nation and says that the troops were two hours late getting to Sumgait when in fact they were the silent witnesses to the atrocities.

My parents couldn’t understand what was happening. Uncle Tolik’s move was so abrupt, so unplanned. In our culture people rarely ever moved away. Violence of this nature made no sense to any of us. It must have been an isolated event, my parents reasoned; it could never happen in our civilized Baku.

Somehow, that birthday was unlike any other that I could remember. We had fun and enjoyed good food, but something was missing, aside from an important family gone from our celebration for the first time ever. There was a feeling of tension and an altogether different atmosphere tinged with apprehension—a vague feeling, that someone was watching us.

I had the same feeling in school, even though nothing seemed to have changed. Perhaps it was only in my mind, but there was something hostile in the air, biding its time.

***

Three decades later, my words strike me by their raw innocence. The pain is still just as sharp as it was back in 1988—and it lingers as it does every birthday, with the memory of that day.

I wrote these words as a 10-year-old child, so hurt by a beloved uncle’s absence from my birthday party. What seemed like a small childhood disappointment turned into a lifetime of loss.

I was not merely losing an uncle; eventually, I would end up losing everything and gaining eternal questions—questions my parents couldn’t answer then and still cannot answer now.

My birthdays were never the same after my traumatized uncle Tolik gathered his family—his wife, his two daughters, and his aging mother—and fled to never return to the city Armenians built. At the time, I did not quite understand the enormity of the change in the air. This change was about to bend the trajectory of our lives across the ocean to the other side of the planet. There was something sinister about the atmosphere as we all dined in the garden, as the adults whispered, and as the Artsakh movement was picking up speed.

And then things began to unravel.

For the next 19 long months, we lived through every painful and terrifying episode of our remaining lives in Baku, mentally going back to that unthinkable three days in Feb. 1988, when young women were burned and old men were cut and the masses of Armenians left their multi-generational homes in the seaside city of Sumgait.

***

Turcotte’s Nowhere, a Story of Exile is available for purchase on Amazon in English and Russian.

It seems that one can never trust or feel comfortable in the company of Turks. No matter how well the relationship is, there is evil waiting to burst out. Never give an inch, never trust them.