I watch the news on the TV screen, see hastily taken images on hand-held mobile phones, images of hands wiping blood, hands carrying guns, hands begging for life, hands and palms pushing and shoving left and right, up and down, whipping through the mad chaos that has befallen the city where my childhood was christened. Aleppo and her ancient streets and habits are about to be baptized in blood once again. The drops of rain hit my window announcing the struggle between winter and spring, washing the new and cherishing the old as time moves closer to join my friends for lunch at a French bistro with Toulousian specialties. In the time between the menu’s appearance and disappearance, the news headlines have grown on our table. A heated conversation has erupted like boiling lead in the furnace, tongues fire red, yellow, and blue shooting toxic gas and moving the liquefied post-transitional metal left and right, like the hands, the hands that move between life and death. I watch my hand on the tabletop sweeping a breadcrumb aside, and see something else. The arguing voices are gradually muffled. And I begin to imagine the 9 p.m. screenings held for the members of Aleppo’s Cinema Club on Saturdays in Cinema Al Kindi. I remember one night, when it was drizzling cold rain in late winter, and I was eager to see Eric Rohmer’s new film “Le Genou de Claire” between his “My Night at Maud’s” (1967) and “Love in the Afternoon” (1973). It was 1970, between the 1967 and the 1973 wars.

Attending this cinematic appointment were my classmates, in a number large enough to make mentioning their names here difficult. The lobby was crowded with the city’s elite—conciliates, professionals, literati, and university students—and then us, with a distinct membership of being underage. The men who ran the Cinema Club from Damascus often sent the films without subtitles, deeming the addition unnecessarily costly for those few who were allowed to watch. And so we sat through a myriad of Western languages, trying to understand what was projected on the screen, and subsequently debating them for days upon days. An idiotic imposition on a small number of people, the establishment wanted them to be “enlightened” by having them “not understand” what they watched; after all, freedom to know had to be limited in this convoluted socialist estate.

Alas, this time it was unmistakably a French film. The loud chitchat of the hot-blooded Aleppo audience indicated that the film had failed to engage the burdened viewers to follow the speech-laden plot for lack of translation. After the famed French ending of “FIN” faded away, the audience mingled and discussed the film in adoration. They had to. How else could they legitimize themselves as being a part of the “elite”? What I had understood from the film was that Jérôme, some sort of a diplomat, was spending his vacation on a postcard-perfect French lake, where he meets Aurora and a few other women, but falls in love with Claire and becomes obsessed with her knee—hence the film’s super creative title “Claire’s Knee.” To be true to the title, at one moment Jérôme does in fact touch her knee! Leaving the adults to the societal games and roles they had to play in that stiflingly oppressed society merrily choking in the hands of socialist policy. We all came together and went to the public bath at midnight as we had always done, but this time in higher numbers, I remember well.

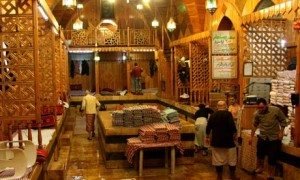

In one of the city’s ancient Turkish public baths located in Madina, the oldest part of the inner city with covered streets that stretched for miles, we found our freedom after taking off our clothes in one of the camekan cubicles and half covering ourselves in peştemal, a cloth checked in navy blue imprints, and slipping our feet into a pair of qabqab, or wooden sandals, as we rushed through the soğukuk, the cooling room, to the hararet, or the hot hall. There was a large common room covered with stones. The floor and the walls supported a conical dome with circles covered with glass to transmit sunlight during the day. I imagined the shafts of sunlight falling upon the naked skin of the females who were allowed to be there only in the daytime. The image would have been the envy of every orientalist painter. Luckily I had experienced this sublime living image when, as a child, I had gone to the bath with my mother, aunts, grandma, and other female neighbors.

The stone floor always burned hot. Men perspired by sitting on the edge with a bowl of cold water in their hands to prevent burning when it got too hot. Many cave-like chambers surrounded this public space where groups, individuals, or couples bathed privately for hours on end. Each cubicle had a stone basin where hot and cold water flowed, and an iron bar at the gate where a man could hang his shroud, that served as a wet curtain to secure privacy from peeping toms..

City folk mostly went to the public bath on either Thursday or Friday nights, and on Saturday nights we always had it sealed off for ourselves, having made reservations in advance.

The year of breaking voices behind us, some were trying to grow mustaches, and a few were unsure of themselves, especially those who had already sensed another flesh. The shy ones never took off their wet shrouds and stood out as an oddity among the many naked teenage boys running amok with bowls of water in hand, playing with soap suds, challenging each other to wrestling games, and fooling about, indulging in the unspoken culture of common bathing when men bond.

We went through the first step of sweating, and the second act of getting rid of dead skin with the help of a kiseh, or a bath glove made with camel hair scrubbing against our skin, until our order of khashkhash spicy kebabs arrived from the famed Kebabji Hagop on large oval aluminum trays with dozens of icy Al Sharq beer bottles. Half-covered in wet bathing cloth, we rushed to the soğukuk, the cold foyer, and sat around a large table to indulge ourselves in bites of ground beef submerged in barbequed mashed tomatoes on Syrian bread (spread with hot pepper paste, thinly sliced onions, and finely chopped parsley sprinkled with cumin and sumac powder), all grilled to a crispy perfection. This merry feast went on with many jokes until everything was consumed and beer bottles emptied to the last drop. Only then were we ready to go back into the bath for a third act and finish off the ritual with a heavily soaped loofa as a last wash. Romantics slept, uttering the names of their secret sweethearts from class, while another’s face breathed in his own vomit. A hard-working student recited a poem we had to learn by heart, and a depressed one isolated himself in a far-off corner, lamenting a failed one-sided love affair. In the organized chaos, I sat in my cubicle next to the overflowing basin, ignorant of the fact that water would be more precious than petrol in the coming decades, instead investing my thoughts in the scene where Jérôme finally places his right hand on the much younger Clair’s left knee, and rubs her kneecap, satisfying the intense attraction built up in the film.

Why was the knee an object of sexual desire, and not her lips, her breasts, her nipple, her beautiful face, her well-rounded young and firm buttocks, her naked and slender legs? It was already past dawn when we dried up with fresh towels while sipping cold mint tea—refreshing after a full night in a hot and humid climate. We packed up to leave. A few of us were heading to the pastry shop to have the city’s famous dish of mamouniye—a heavy load of semolina with ghee and plenty of sugar, sprinkles of cinnamon, and pistachio shavings topped with heavy cream and served with salty cheese on the side. This was an aphrodisiac a groom would beg for. A few others went home, and the disciplined ones rushed to their Sunday morning Boy Scout camp.

Over the following weeks my closest friend H.P. and I argued about the film, endlessly deciphering the impersonal dialogue reflecting what the French do in daily life and what is evident in their films, where talk goes on casually while lovers snatch each other, switch sides, while old men fall in love with the young daughters of the women they love, an uncle falls for his niece, or a stupid young boy romantically falls in love with an older woman who is attracted to his father. The combinations are varied, but the mystery of Clair’s Knee lingered on. I had found the perfectly shaped Vera and her slightly older sister Hera’s shoulder desirable, but not once their knees. Clair’s Knee grew obsessively with no answer in sight. We discussed love, eroticism, attraction, sensuality, and sexuality, developing skills in abstract thinking without even being aware of the fact.

Slender Hera and curvaceous Vera were my age and worked as seamstresses in my parents’ tailor shop. The Middle Eastern habits of combining work with socializing had made the charming and attractive sisters essentially adopted daughters to my mother, who only had sons. The work shop and our house were all in one place, and the girls often stayed after work, or visited on their days off, or on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays when my father was playing cards in the social club, my mother was in church praying to the gods, and my younger brothers were at the playground. Sheltered from malicious neighboring eyes and gossiping mouths, we felt free to experiment being in each other’s arms by playing nameless games that involved the sense of touch.

On an early Sunday afternoon, almost a month after that night in my apartment, Vera wanted to make coffee and excused herself to the kitchen (a pretense to leave Hera alone to savor her fictional headache by reclining on my bed). Intending to show care, I approached her and placed my hand on her forehead to see if she had a temperature worth worrying about.

In my room was a tall antique mahogany dresser a few hundred years old, with hand-carved frames almost touching the ceiling and a giant mirror serving as a door. A few wicker chairs in the corners held piles of Armenian books and gossip magazines in Arabic from Beirut and Cairo. A single window framed in azure green filtered daylight through the wooden blinds and allowed a breeze into the room through the loosely hung mosquito net when there was a change of air in the hot summers. On the green-tinted white marble floor was a wooden stool I used to sit on and watch the street activity below our balcony. I looked at Hera again, trying to plan my next move, and gracefully pointed at the stool.

– Come. Sit here.

Surprised, she smiled, and sat on the stool.

– What are we doing!

– I want to touch your knee.

– What’s wrong with my knee!

– I want to know what is right with a knee, I said.

In slow motion she pulled up her white denim skirt and revealed a pair of kneecaps. I asked her to relax and lean against the white wall, and positioned her in the center of the closet’s mirror in a composition Velázquez would have loved to see. She took a deep breath and shut her eyes. Trapped in Cleopatra-styled hair that framed her perfect jaw, high cheekbones, and tiny nose, she trusted her back against the wall. I went down on my knees, positioning my head against her kneecap… I felt her hand touching my skull and her hot breath blowing away my hair away from my forehead. I looked up, our eyes gazing into each other closely, eyelashes almost touching each other, our lentils frozen like the tiny rock islands of the Mediterranean cost of Maddalena north of Sardinia. Heaving and breathing each other’s steam, my left hand grabbed her neck, gently pulling her closer. Lust, I thought, is one thing I hadn’t yet discussed with my friend in the context of the film. Perhaps ridden with a sense of shame for having diverted my original take, or having reached the limits of a dare, she pushed me back and, to my dismay, wanted to place my hand on her knee again. At this time, the unexpected early spring wind blew in the city’s polluted air. The loose window shutters flapped left and right, banging against the limestone walls and sending dust into my room and her lungs, leaving her gasping for air and sneezing continuously on my face, ending an experience in disgust and making me the warden of an experience I could not share. I wished to meet Eric Rohmer to tell him, “Your knee fantasy does not work well and it is not fair.” The door moved; it was Vera pushing it open with her left elbow while holding a tray with three cups of coffee that had gotten cold while she waited for the perfect moment to come in, with a grace of a nun and twinkling eyes showing both shame and jealousy of an adulteress sister. Above the rims of the cups was her bust, revealing cleavage; spellbound, I looked below the tray, but could not see her knees hidden in black trousers.

With the virus of immigration well incubated in my family, we departed to New England to start a new life, not knowing that we would forever be burdened with the weight of the past and that yester-times would become a major tool for immigrants to weave through the present and the next spinning sun. On the canvas of my memory, I saw friends who had nakedly paraded their blossoming youth in front of me. I have no clue who did what since that day in the bathhouse, but I heard through the grapevines that Hera and Vera were married and living in France. H.P. has been living in the U.S., and not long ago another friend who had aspired to become a priest was killed in a car accident while he was on his way from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

I still don’t know what happened to the knee that belonged to the aloof and beautiful Claire vacationing in the pristine French countryside. Now, years later, in the French bistro, while finishing a bowl of slowly cooked hearty cassoulet on a cold winter day with my friends—united in sipping wine and continuing to disagree while predicting the political outcome of the region and what may be awaiting Aleppo—a waitress appears to clean the table and make it ready for the next course. I watch the young waitress with her hair dyed blonde and her semi-perfected nose approach our table with a tray of Lebanese-made French pastries decorated with berries and cherries, shaved almonds, and sugar powder atop puffed dough and heavy cream. Behind her black apron is a short skirt exposing a knee that touches the loosely hanging edge of the table cover when she bends down to place the plates. And like Vera, she reveals her cleavage. I catch my confused hand trying to find its way to her knee, which is begging for a caring hand, but finally rest it on the table before grabbing a fork for a sweet bite.

– What’s your name, I ask, when she moves to serve my friend.

– Grace, she says, with a smile exposing teeth white enough to advertise toothpaste.

I think I say, “You have beautiful knees.” And cherish the memories of a handmade journey started at a knee and aborted with a sneeze, realizing that Rohmer may had had something right in his frame that needed time to see instead of watch…

Aug. 10, 2012. Boston/Watertown.

It was a sweet story with a certain modesty that we Americans don’t value as much as we should.

Thank you for this beautiful story. As I was reading the first paragraph, I was expecting a well-informed political commentary on the civil war in Syria, but the story morphed pleasantly into a touching memoir, and I felt transported into its special time and place by the detailed, loving descriptions of the scenes.