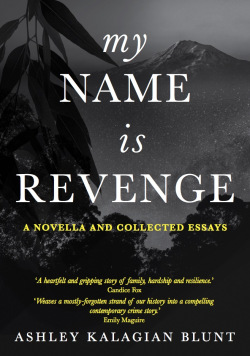

My Name is Revenge: A Novella and Collected Essays

My Name is Revenge: A Novella and Collected Essays

Ashley Kalagian Blunt

Spineless Wonders, 2019

156 pp.

I have three criteria for judging a book. First, it must follow the “show not tell” principle; I go willingly along for the ride only if my emotions are engaged by the characters, descriptions and actions. I also want to wonder what’s going to happen next; the more often I do, the more I enjoy the journey. There must also be a satisfying conclusion. When there are no out-of-character moments and, in hindsight, the ending is a realization not a revelation, I’m satisfied. A bonus occurs when long after I’ve come to the last page, I’m still thinking about certain scenes or contemplating the book’s message. Ashley Kalagian Blunt has delivered all this and more in her novella and collected essays, My Name is Revenge.

In the interest of full disclosure, when the author offered to review my book, Grit and Grace in a World Gone Mad: Humanitarianism in Talas, Turkey 1908-1923, I reciprocated, as our books were being published around the same time. Her review was published in The Newtown Review of Books last month. I was impressed by her analytical skills and astute observations, so I had no concerns that her essays would be equally well-written. But nonfiction uses different writing muscles than fiction, so I was curious about her ability to write compelling fiction. I needn’t have worried. She is just as deft with her novella.

My Name is Revenge starts with a fact: “On 17 December 1980, at 9:47 am, two men shot the Turkish consul-general to Sydney and his bodyguard near the consul’s home in Vaucluse. The assassins aimed, fired and vanished.” The assassination was part of a number of international terrorist attacks carried out by the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide from 1973 to the early 1990s “in retaliation for the injustices done to the Armenians.” From there, Kalagian Blunt imagines the story of Vrezh, a young immigrant, who fears that his moody, secretive brother, Armen, might have been involved in the crime.

Vrezh, whose name means “revenge” in Armenian, trails Armen and eventually insists on involving himself in whatever nefarious scheme Armen and his questionable cohort are planning. He’s not quite sure exactly what that is until much later, but he continues to show up and put his skills to work on their behalf. Though Vrezh says he’s committed to the cause, his seems to be a commitment without heart. His family had emigrated from Egypt when Vrezh was eight, and brought with them his grandfather, a survivor of the genocide in Anatolia. Vrezh had grown up with the many stories of the deportations and massacres, and knew the emotional toll the experience had on his grandfather. His participation along this vengeful path with Armen seems to stem from a sense of duty or inevitability or an unspoken directive to “live up to his name.”

On the surface, the novella is a suspenseful tale of revenge, right down to its explosive ending. But the underlying thread of the story is the mostly unconscious conflict within Vrezh about the validity of his quest, and about the important concepts of guilt, innocence, justice and revenge. Kalagian Blunt has laid the groundwork for this with a carefully constructed plot and references to “the uncomplicated naivety of childhood”, to an incident where “the victim became the avenger”, and to the fact that history isn’t always “so straightforward.”

Accompanying the novella are collections of photographs taken by the author on her 2012 trip to Armenia and three selected essays. In “Writing Violence, Arousing Curiosity,” Kalagian Blunt describes her background as a Canadian of Armenian and Polish descent, her own immigration to Australia and how she came to write the novella. In “The Crime of Crimes” she discusses genocide, framed around the work of Norman M. Naimark, starting with the importance of the Holocaust and “its place within an historical continuum.” The essay entitled “Life After Genocide” was originally published in 2015, so there is some repetition of ideas in the other two essays. But this one is perhaps the most personal, giving insight into the author’s perspective on racism, moral courage and acts of kindness—including her own.

Ashley Kalagian Blunt said that she’ll probably be writing about the Armenian Genocide for the rest of her life, not only because it’s part of her historical roots, but because crimes against humanity are “a part of everyone’s story.” I hope she will. Hers is a thoughtful, articulate and informed voice that deserves to be heard.

Be the first to comment