Shifts in the balance of power across Eurasia are prompting states to seek new alliances and recalibrate their security partnerships. These systemic changes compel governments to reassess cooperation with external actors in order to safeguard national security and construct resilient security architectures. Armenia offers a compelling case study: as a small state navigating a rapidly evolving regional order, its diversification strategy and deepening military-technical ties with France and India reveal how systemic pressures shape small-state behavior.

This article applies Stephen M. Walt’s balance-of-threat framework and Thomas Schelling’s theories of deterrence and compellence to analyze Armenia’s strategic choices. Rather than framing Armenia’s realignment as a mere post-war reaction, the article situates it within a broader reconfiguration of Eurasia’s security architecture. The central hypothesis advanced is that Armenia’s turn toward France and India is driven not by opportunism or cultural affinity, but by structural geopolitical processes: the consolidation of a Pakistan–Azerbaijan–Turkey axis, which incentivizes India to project influence westward, and Russia’s partial withdrawal from the South Caucasus, which enables France — aspiring to assert European leadership — to expand its presence. Armenia’s partnerships thus seek to leverage great- and middle-power rivalries to recalibrate the regional balance of power and secure a more advantageous strategic position.

I. Introduction

Following the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Armenia significantly reoriented its defense policy. Between 2020 and 2025, defense spending increased by 128%, reaching $1.7 billion — the largest proportional increase in Armenia’s history. The procurement program, totaling approximately $2.5 billion, includes major contracts with India for 155-mm ATAGS towed artillery systems, 72 MArG self-propelled guns, Pinaka multiple-launch rocket systems, Akash surface-to-air missile systems, Zen anti-drone technologies, Konkurs-M anti-tank missiles, small arms and ammunition.

In 2024, Armenia and India also signed an agreement on military training and institutional cooperation. By the end of that year, India had solidified its position as Armenia’s leading supplier of weapons and ammunition, accounting for 43% of total imports.

II. Theoretical framework

Balance-of-power theory provides a strong explanatory lens for Armenia’s decision to initiate military-technical cooperation with India. Within the balance-of-threat framework, states respond to perceived danger through either balancing or bandwagoning behavior.1 With few viable allies, limited capacity to influence regional outcomes and the absence of credible external assistance, Armenia accommodated Moscow as a last resort.

Armenia had previously engaged in bandwagoning with Russia — a choice driven by structural constraints rather than preference.

This strategy ultimately proved costly, leaving Armenia overdependent on a single partner and vulnerable to shifts in that partner’s priorities. Having experienced the limits of bandwagoning, Armenia subsequently adopted a balancing approach, reinforcing the logic of balance-of-power theory. The initially transactional and mutually beneficial cooperation with India, launched in 2022, fits this logic and serves as a clear declaration of strategic intent.

From India’s perspective, aligning with the more vulnerable side increases a new entrant’s influence, as weaker coalitions have a greater need for assistance. By contrast, joining a stronger side reduces leverage and increases exposure to a partner’s shifting priorities2

. A safer strategy is to ally with actors unable to dominate their partners, thereby avoiding dependence on overbearing patrons3

— one of the principal reasons Armenia turned to India. This marks the starting point of Armenia’s balancing behavior.

III. Armenia-India cooperation

Yerevan continues to strengthen its military ties with New Delhi. Given Armenia’s geography, Iran has emerged as a key link in the Armenia–India cooperation chain. Central to this dynamic is the prospective International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which aims to connect India to Russia and Europe via Iran, adding significant strategic weight to the trilateral relationship.

During their most recent meeting, the three parties emphasized expanding cooperation in connectivity, the INSTC and Armenia’s “Crossroads of Peace” project, while highlighting the strategic importance of Iran’s Chabahar port. They also reviewed initiatives to strengthen ties in trade, culture and people-to-people exchanges, signaling an intention to evolve the partnership into a multifaceted strategic alignment.

Despite these declarations, however, no substantial economic projects or trade agreements are currently in place. Cooperation with India remains primarily defense-centered. While a gradual shift toward broader engagement is possible, it remains largely aspirational at this stage. New Delhi’s cautious geopolitical positioning is further shaped by its long-standing rivalry with Pakistan and the growing strategic importance of Azerbaijan — another participant in the North–South Transport Corridor.

IV. Regional context and rival blocs

Pakistan meets all four criteria of threat as defined by balance-of-threat theory: aggregate power, proximity, offensive capability and offensive intent4. It remains India’s principal challenger, a reality underscored by the India–Pakistan crisis of 2025. The prospect of a fourth outcome beyond win, lose or draw — namely, disaster — fundamentally shapes the behavior of nuclear-armed rivals.

In a metaphorical chess game, disaster is triggered when specific moves by both players coincide, imposing penalties that leave both sides worse off than a conventional defeat5. This risk of mutual catastrophe acts as a brake on escalation and was likely a key factor in halting the near-war of 2025. Yet the rivalry persists, compelling both states to seek new arenas of competition beyond South Asia, including the South Caucasus.

For India, Azerbaijan presents a double-edged risk. The NSTC route through Azerbaijan provides rail and road connectivity via Iran, Azerbaijan, Russia and Kazakhstan, potentially generating $250–300 million annually in transit revenues for Baku. At the same time, Azerbaijan’s capacity to destabilize the South Caucasus could disrupt the corridor and weaken India’s strategic access to the Iran–South Caucasus segment of the route. Regional stability is therefore a key precondition for India’s long-term connectivity strategy.

It is also important to note that India has not altered its position on the Nagorno-Karabakh issue and continues to recognize the region as part of Azerbaijan. By contrast, Kashmir remains a strictly bilateral dispute for India, while for Pakistan it is an ideological and religious cause that Islamabad seeks to internationalize. This asymmetry helps explain India’s rejection of pan-Turkic ambitions and past proposals for the so-called Zangezur Corridor.

For Armenia, emerging connectivity initiatives present both opportunity and vulnerability. The U.S.-brokered “Trump Route” promises reopened transport links, an initial $145 million tranche of American investment and deeper integration into regional trade networks. Yet it also grants Azerbaijan a direct land route to Nakhichevan and Turkey, strengthening the very axis that threatens Armenia’s security. Compounding this dilemma, Armenia’s establishment of diplomatic relations with Pakistan risks straining ties with India, one of its key new defense partners.

Participation in these initiatives therefore demands careful calibration. Security considerations ultimately take precedence over ideological alignment, and alliances based solely on shared identity rarely endure when confronted with pragmatic strategic interests6

— a reality reflected in the Armenia–India partnership.

V. Armenia-France cooperation

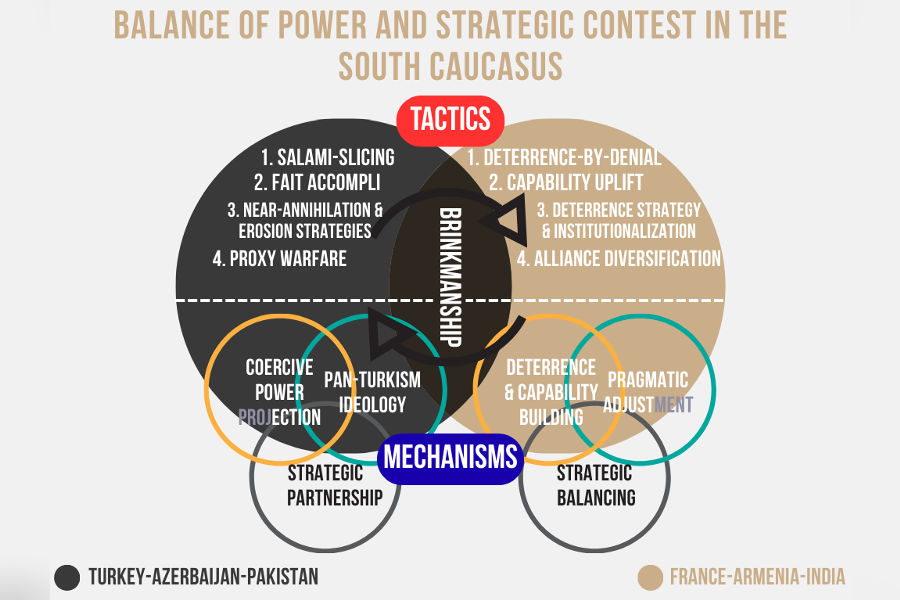

France’s engagement with Armenia is best analyzed through deterrence theory. Deterrence by denial — widely considered more reliable than punishment — aims to make aggression infeasible by undermining an adversary’s confidence in achieving a quick victory. This approach is particularly relevant in Armenia’s case, given Azerbaijan’s repeated use of coercive diplomacy and “salami-slicing” tactics — including incursions into Armenian territory — to alter the status quo without provoking major retaliation.

While Paris cannot credibly threaten large-scale retaliation in the South Caucasus, it can make renewed aggression unlikely to succeed. This strategy is scalable, coalition-compatible and politically sustainable for the European Union. It also reflects a broader logic of dissuasion, shaping an aggressor’s cost–benefit calculus by increasing the costs of escalation while signaling that stability remains the preferable outcome.

France’s deterrence-by-denial approach operates across three interlinked layers:

Layer 1: EU transparency and early-warning measures

The EU Monitoring Mission in Armenia (EUMA), deployed in 2022, enhances border visibility, attribution and early warning, narrowing the window for a fait accompli and raising the political cost of any surprise attack. As deterrence theory emphasizes, credible denial depends on the aggressor believing that surprise or a quick victory is unlikely. By making any incursion immediately observable, EUMA raises the political cost of “salami-slicing” tactics and complicates efforts to alter the status quo incrementally without triggering an international response7.

Layer 2: Bilateral capability uplift

French arms transfers — including three GM-200 radars, 50 Bastion armored vehicles, 36 CAESAR 155-mm self-propelled howitzers and various small arms and equipment — strengthen Armenia’s air-surveillance coverage, protected mobility and counter-battery capabilities, directly complicating any rapid military breakthrough. These measures are set up to be further institutionalized through the forthcoming France-Armenia “strategic partnership” document, which formalizes defense cooperation and signals a sustained long-term commitment, directly addressing the “capability + will” requirement for credible deterrence8.

Layer 3: Mini-trilateral formats

Emerging formats with partners such as India, Greece and Cyprus amplify deterrence-by-denial effects through joint training, interoperability and information-sharing, increasing the costs for any potential aggressor without requiring formal alliance commitments.

Layer 1 of France’s approach focuses on transparency and early-warning mechanisms provided through the European Union. The EU first deployed a monitoring capacity in October 2022, followed by the launch of the full EUMA mission in February 2023. More recently, France once again advocated for its extension, framing it as a means of curbing hostilities and preventing escalation. This advocacy served as a clear signal to Azerbaijan, combining deterrence by denial with a broader strategy of dissuasion — raising the political cost of renewed aggression while reinforcing that stability and dialogue remain the preferable path.9

France’s engagement, however, predates the deployment of EUMA. During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, President Emmanuel Macron openly defended Armenia, supported international ceasefire efforts and emphasized Armenian rights rather than maintaining strict neutrality. This political positioning was followed by a French Senate resolution, adopted almost unanimously, calling on the government to recognize the former Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. This diplomatic démarche was subsequently reinforced by the deployment of EUMA and France’s continued advocacy for its extension, forming the first layer of a broader deterrence-by-denial strategy. Together, these steps sent a strict signal to Azerbaijan, reflecting a key principle of deterrence theory: “The deterring state must make its commitments precise and ensure the potential aggressor clearly perceives them”10.

If Layer 1 pre-built tensions through diplomatic démarches and EU monitoring, Layers 2 and 3 focus on expanding these efforts into tangible military and institutional measures. These include arms sales, the forthcoming France-Armenia strategic partnership and broader institutional cooperation — recently reinforced by a Franco-Armenian Declaration of Intent to enhance civil aviation safety through joint investigation capacity and expertise sharing. Layer 2 thus marks the shift from diplomatic signaling to concrete security provision.

Deepening Armenia-France defense ties have, in turn, heightened tensions with Baku. Rhetoric escalated notably after Paris accused Azerbaijan of backing unrest in New Caledonia, effectively transforming bilateral relations into an openly adversarial one. Azerbaijan has responded with “mirror steps,” intensifying its partnership with Turkey — a relationship that has grown markedly closer since 2020. The Turkey-Azerbaijan strategic alliance, formalized by the 2021 Shusha Declaration, significantly enhances Baku’s geostrategic and military posture by committing both states to joint modernization efforts and coordinated action. In the post-war period, Azerbaijan has increasingly modeled its armed forces on the Turkish military and conducted frequent joint drills, cementing a unified deterrent front.

For Armenia, this axis represents not merely a military challenge but a comprehensive existential threat. Turkey’s decisive involvement in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war — including the transfer of Syrian fighters, the supply of Bayraktar TB2 drones and the embedding of Turkish instructors — enabled Baku to achieve rapid battlefield dominance. The campaign combined near-annihilation, through the physical dismantling of Armenia’s defensive capacity, with an erosion strategy that raised the costs of continued resistance to unbearable levels, ultimately forcing Yerevan into compliance. In terms of coercion theory, this amounted to a hybrid of deterrence — dissuading Armenia from escalating under the threat of Turkish intervention — and compellence, employing force until Armenia conceded11.

This coercive success underscores why France’s strategy prioritizes deterrence by denial over punishment. Preventing a swift fait accompli and eroding Baku’s confidence in achieving another rapid victory is more credible and stabilizing than merely threatening retaliation after the fact. At the same time, the deepening Turkic alliance presents France with a complex strategic dilemma: greater support for Armenia risks limited confrontation with Turkey, a fellow NATO member.

Layer 2 has an additional sublayer reflecting a competition in commitment credibility. France implicitly contrasts its bilateral cooperation with Armenia with the fading reliability of Armenian-Russian defense ties, opting instead to couple capabilities to clearly defined objectives and to sustain a consistent process of commitment. As one of the main providers of aid to Ukraine, and a state increasingly critical of Russia’s conduct in other regions (e.g. in the Sahel), France’s entry into the South Caucasus — long regarded by Moscow as its sphere of influence — reflects both strategic ambition and reaction to Russia’s declining credibility.

The shifting competition between Moscow and Paris shifting across multiple regions — the Sahel, the South Caucasus and Ukraine — reflects the logic of the interdependence of commitments: “A state must demonstrate resolve in one theater so that its deterrent credibility is believed in another”12.

Layer 3 unpacks the next and final stage of this duo-versus-duo confrontation, as it gradually evolves into a broader trilateral balance of power. On one side stands the Pakistan-Azerbaijan-Turkey alignment; on the other, the emerging France-India-Armenia axis, with Greece and Cyprus potentially becoming involved — a development to be explored in a separate article.

This dynamic exemplifies trilateral realism, in which blocs form to balance one another. India’s engagement is particularly notable. In February 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a pivotal visit to France, underscoring the depth of Indo-French strategic ties. Defense cooperation remains the cornerstone of this relationship, marked by France’s consistent supply of advanced military technology — including Rafale fighter jets and Scorpène-class submarines — which has significantly strengthened India’s air and naval capabilities. The Jaitapur Nuclear Power Project further illustrates the breadth of this strategic partnership. Space collaboration is also significant, with ISRO and CNES undertaking joint missions and data-sharing initiatives.

VI. Armenia’s security architecture: Integration of partnerships and strategic implications

Viewed against this backdrop, the France–India–Armenia convergence appears to be more than coincidental. It suggests a shared geopolitical agenda at both the regional and global levels, driven by overlapping security and economic interests and by the need to counterbalance the opposing trilateral bloc.

On the other side, Pakistan’s involvement dates back to the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, when it expressed early solidarity with Azerbaijan and reportedly facilitated the transfer of militants to the conflict zone. This episode marked the first tangible sign of security cooperation that later evolved into a more structured partnership. Azerbaijan’s recent purchase of 50 JF-17 Block III fighter jets from Pakistan — to be fitted with Turkish-made missiles and enhanced with Turkish avionics — is part of this trajectory, significantly boosting Baku’s air-combat capabilities and signaling that this trilateral bloc is preparing for long-term strategic coordination.

Moreover, the Lachin trilateral summit marked a decisive turning point, moving the relationship from symbolic support to a concrete roadmap for deeper political, economic and military integration between Pakistan, Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Indeed, the current situation mirrors a competition in risk-taking rather than a straightforward clash of force. With multiple external powers now engaged, the South Caucasus has become a theater in which each side tests the other’s nerve through posturing and calibrated signals of resolve13.

Turkey’s high-profile military exercises, Pakistan’s expanding military transfers and training support and Azerbaijan’s rapid rearmament collectively signal a willingness to escalate — a form of deterrence by intimidation meant to pressure Armenia and deter its partners. Conversely, France’s diplomatic backing of Armenia and discussions of defense cooperation, together with India’s strategic engagement, signal that Azerbaijan and its partners cannot act with impunity and that escalation would carry international costs.

The current peace agenda pursued by the Armenian government illustrates how a small state seeks to balance relations with its immediate neighbors while navigating competing security pressures. This approach reflects an attempt to de-escalate regional tensions without compromising long-term sovereignty. Whether Armenia’s current policy toward Turkey and Azerbaijan constitutes pragmatic balancing or a renewed form of bandwagoning, however, lies beyond the scope of this study and should be examined separately.

This brinkmanship14 introduces a new layer of risk: miscalculation or overconfidence could ignite an unintended confrontation none of the parties truly seeks, including the dangerous prospect of a France-Turkey standoff. For Armenia, this environment represents both an opportunity and a stress test for its evolving security architecture. Its partnerships with France and India — designed to reduce dependence on Russia and build a diversified network of security guarantees — are now unfolding under the shadow of a Pakistan-Azerbaijan-Turkey trilateral deterrent alliance.

This “changing balance of power” creates a fragile but high-stakes equilibrium in which Armenia’s security strategy must balance deterrence with restraint, carefully managing risk while still asserting sovereignty. The outcome will ultimately determine whether Armenia’s evolving security architecture becomes a platform for regional stability or a trigger for further escalation in the South Caucasus.

VII. Conclusion

This analysis confirms the central hypothesis of the article: Armenia’s deepening partnerships with France and India are not ad hoc reactions — such as those driven by cultural affinity — but a structural adaptation to a reconfigured regional order. This realignment potentially elevates the roles of New Delhi and Paris while introducing both strategic opportunities and risks. The strategy is deliberately aimed at offsetting the Pakistan–Azerbaijan–Turkey axis and reducing overreliance on Russia, thereby constructing a more resilient and diversified security architecture.

1. bandwagoning behavior: Walt, Stephen M. 1985. “Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power.” International Security 9 (4): P. 5. ↩︎

2. shifting priorities: Walt, Kenneth N. 1979. “Theory of International Politics.” Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, p. 127. ↩︎

3. overbearing patrons: Walt, “Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power,” p. 6. ↩︎

4. offensive intent: Ibid, p. 9. ↩︎

5. conventional defeat: Schelling, Thomas C. 2008. “Arms and Influence. With a new preface and afterword.” New Haven and London: Yale University Press. P. 100. ↩︎

6. strategic interests: Walt, “Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power,” p. 24. ↩︎

7. international response: Mazarr, Michael J. 2021. “Understanding Deterrence.” In NL ARMS: Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2020, edited by Frans Osinga and Tim Sweijs, 13-28. Dordrecht: Springer. Pp. 25-26. ↩︎

8. credible deterrence: Schelling, Thomas C. 2008. “Arms and Influence,” pp. 36-38. ↩︎

9. preferable path: Mazarr, Michael J. 2021. “Understanding Deterrence,” p 19. ↩︎

10. perceives them”: Schelling, Thomas C. 2008. “Arms and Influence”, p. 44. ↩︎

11. Armenia conceded: Biddle, Tami Davis. 2020. “Coercion Theory: A Basic Introduction for Practitioners.” Texas National Security Review 3 (2): 64-84. Austin: University of Texas, LBJ School of Public Affairs. Pp. 94-109. ↩︎

12. in another”: Ibid, p. 55. ↩︎

13. signals of resolve: Schelling, Thomas C. 2008. “Arms and Influence”, p. 91. ↩︎

14. brinkmanship: Thomas C. Schelling, “Arms and Influence” (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 91. Schelling defines brinkmanship as “the creation of risk — usually a shared risk — [as] the technique of compellence that probably best deserves the name of ‘brinkmanship.’ It is a competition in risk-taking. It involves setting afoot an activity that may get out of hand, initiating a process that carries some risk of unintended disaster. The risk is intended, but not the disaster.” ↩︎